Interpellation by the Force: Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses in The Force Awakens

by Simon Orpana

Published December 2017

Abstract:

Following Nicholas Brown’s and Fredric Jameson’s ideas about pastiche and art under postmodern capitalism, this essay argues that Star Wars: The Force Awakens is not so much a film as a means of interpellating a new generation of fans into the Star Wars universe and its attendant merchandising empire. I introduce the idea of Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses as an adaptation of Louis Althusser’s theory of ideology to the neoliberal context, where state apparatuses have been retooled and augmented by cultural apparatuses that manage desires and expectations at the level of bodies, ritual, and affect. In this context, the Death Star emerges as an image of the disavowed totality that global capitalism must repeatedly conjure and dispatch as it projects itself, expansively, into the future.

It is a curious feature of Star Wars: The Force Awakens that, despite the victory of the rebels at the end of Episode VI (Return of the Jedi, 1983), and despite the death of Darth Vader, the Emperor, and the destruction of the second Death Star, Episode VII (The Force Awakens, 2015) seems to return to where the franchise started in Episode IV (A New Hope, 1977)—with a rag-tag band of freedom fighters combating a totalitarian army and their planet-destroying weapon. Rather than delving into the difficulties of restructuring a Galactic Republic from the chaos that was sure to follow the death of the old Emperor, the new film baldly sidesteps these issues and any of the interesting grey areas that might have been explored with the former rebels assuming a constitutive role within the new government. Instead, The Force Awakens offers the same clear-cut, good guys vs. bad guys, “subalterns” vs. “totalitarians” that characterized A New Hope. It is as if the Star Wars mythology only works when the protagonists are embattled underdogs and the bad guys are Fascists.

A second peculiarity consists of the fact that, as soon as the plot repairs to the desert planet Jakku where we meet Rey, the film resembles not so much an actual, original movie as an extended commercial for the Star Wars franchise itself. By identifying with Rey and Finn, viewers are able to participate in a fantasy whereby unsuspecting neophytes stumble upon the legendary apparatuses of the original trilogy: the Millennium Falcon, the grizzled space pirate and his Wookie sidekick, the battle against a technological monstrosity, and so on. The film essentially re-creates A New Hope (1977) within an added frame that addresses, and essentially erases, the largely unpopular prequels made by Lucasfilm (The Phantom Menace [1999], Attack of the Clones [2002], Revenge of the Sith [2005]), allowing a new generation of fans to experience the franchise afresh. In this way, The Force Awakens acts as a mechanism for what I call Star Wars interpellation: summoning a new generation of fans and inscribing them into the ideology of the Star Wars universe. But what is this ideology? This essay details how ideological mechanisms associated with popular culture allow for the Star Wars franchise to respond to historical shifts in the economic and cultural context of late, Western modernity while yet perpetuating hierarchies and values essential to the reproduction of global capitalism.

Interpellation Then and Now: Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses

In his 1970 essay, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards and Investigation),” Louis Althusser articulates the term “interpellation” to describe how capitalist relations are reproduced via “Ideological State Apparatuses,” or ISAs, such as churches, schools, the family, the legal system, the press, and culture in general (208). These operate, not just at the level of ideation or speech, but also through material, ritualistic activities often supported by institutional structures (207-211). Participating in jury duty, for instance, is not merely about determining the guilt or innocence of an alleged perpetrator; the jury process itself has a pedagogical role for all involved, reinforcing society’s juridical structures, its hierarchies and power relationships. Regardless of the outcome of a particular trial, the members of the jury are interpellated into respect for and submission to the law through their mere participation. Democratic voting offers another example: whatever the outcome of the election, the very act of voting signals a subject’s tacit acceptance of, and interpellation by, a web of background power structures and ideologies concerning the relationships between government, economics, and politics, the division between the public and private spheres, and the temporality of political participation itself.

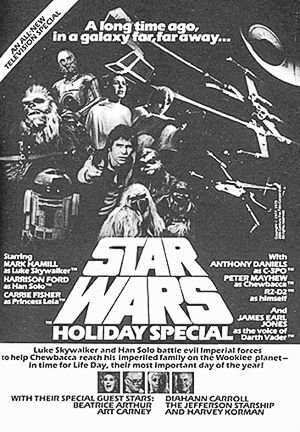

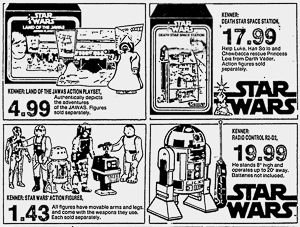

Though ideology constitutes an imaginary relationship to real and contradictory social relationships, it is nevertheless “endowed with a material existence” in the practices and rituals that serve as ideology’s vehicle (Althusser 215). Ideology is thus inseparable from embodied practices, such as the family ritual of watching Star Wars films at the cinema or at home. Far from being the merely formal supports for ideational content, such practices are constitutive of ideology itself: the Star Wars franchise is primarily a drama about family and friendship—two of the last forms of collective solidarity that capitalism tolerates, and indeed must tolerate if the system is to be reproduced (one can dismantle other forms of socialized wealth, but one can’t have a new generation of worker/consumers without partners to birth them, and family and friends to socialize them). The ritualistic practices associated with Star Wars in the form of toys, video games, comics, merchandise, fan culture, and film-viewing practices are likewise centered upon friends and family. For example, the way in which the recent instalments to the film franchise are being released in December, and the common practice of watching Star Wars films, both new releases and DVDs of the older films, at this family-oriented time of year, reinforces intergenerational bonds, even while the actual narrative of the films delivers a similar message of friendship and familial solidarity. These messages are further reinforced by the toys and merchandise that are released and promoted in the lead-up to holiday gift-giving, allowing the ritual of playing with Star Wars toys to be reproduced for new generations of young consumers. In these embodied and material practices, form and content are mutually reinforcing and constitutive.

Althusser’s theory points towards the mutual implication of affect, ideation, and ritual in a manner that allows us to challenge claims that contemporary society has moved “beyond ideology.” Such claims, from Frances Fukuyama’s prediction of an “end to history” after the demise of alternatives to liberal-democratic capitalism, to anxieties about the roles played by technology in hastening the end of politics as we know it miss an important point that Althusser’s analysis underscores: the theory of the ISAs reveals ideology to be, not just a set of ideas or abstract world-views, but tethered to embodied practices that include multiple registers, institutions, and material structures for its successful reproduction. The understanding of how power, ideation, and subjectivity are enmeshed has been further explored in the contemporary turn towards affect, performance, and post-structuralist theories of identity and culture. Sarah Ahmed, Lauren Berlant, Judith Butler, Brian Massumi, Jon Makenzie, and many others have helped to articulate the dynamics of affect, performance, and subjectivity in what Slavoj Žižek has described as postmodern, permissive society based on an injunction to enjoy, rather than the prohibitions and disciplinary strictures that attended industrial capitalism (In Defense 30-31). These theories respond to a mutation in capitalism itself, whereby the more stable identities and institutions associated with the post-World War Two, Fordist social pact have given way to a much more fluid “postmodern” form of global, neoliberal capitalism (Bauman 5-26; Jameson, Postmodernism 35-36). The theory of the ISAs was articulated at the meridian between these two iterations of capitalism, making it a useful concept for addressing the persistence of ideology despite the seeming eclipse of this category by a globalized market economy that disguises its modes of exploitation beneath a veneer of freedom associated with consumerism, globalization, precarious work, and entertainment.

Althusser specifically describes his theory as an answer to the question: “how is the reproduction of the relations of production secured?” (209, italics orig.). This question becomes all the more pressing for understanding a period, such as occurred in the late 1970s through the 1990s, when capitalism itself was undergoing a seismic shift involving what many authors have recognized as an eclipse of the kinds of disciplinary enclosures such as church, school, and factory that served, under the auspices of Fordist/industrial capitalism, as primary sites of ideological reproduction (Deleuze, Massumi 19-29, Hardt and Negri 22-27). With the capitalist system undergoing what in the West appeared as a sea change in terms of the kind of work, life experiences, and identities that subjects could expect, a shift from an industrial order of production based on disciplinary enclosures, to a “post-industrial” society based on more permissive modes of control, the problem from the point of view of capital was how to maintain its fundamental structures of privatization, exploitation, and the expansion of profit.

Althusser privileges formal education as the central apparatus of ideological reproduction, though he names a series of others: politics, communications, family, religion, and culture, all of which work in concert to reproduce the dominant system (210). Arguably, however, the rise of global, neoliberal capitalism in the past four decades has augmented the role played by culture in maintaining and legitimizing capitalism, while other forms of socialized wealth and resources undergo radical restructuring, privatization, and dissolution. In this new constellation, the different apparatuses named by Althusser still work in concert, but the ways in which they work have changed, and culture plays a much more prominent role in managing the ideological mechanisms that naturalize the changed functioning of other sites, like government, education, and religion.

To reflect the way the ISAs have been augmented and sometimes superseded by cultural mechanisms based on pleasure and consumption, I would advance a new term. Building upon Michel Foucault’s concept of the dispositif, as further articulated by Giorgio Agamben, Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses describe the ways in which culture works at the level of bodies, spaces, temporalities, and practices to reinforce and possibly challenge or upset dominant power structures (Agamben 1-24, Foucault, Power 194-6). Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses, or BCAs, combine narrative, affect, and corporeal practices to establish socially constructed spaces of representation that play a key role in shaping the parameters by which subjectivities are imagined and performed in the context of globalized, postmodern capitalism. In an era that has seen significant dismantling of the State Apparatuses associated with Fordism’s welfare mechanisms, and the retooling and strengthening of what Althusser calls “Repressive State Apparatuses,” or RSAs, (207-8) in service of the interests of deterritorialized, transnational capital, BCAs have taken up some of the functions formerly performed by the ISAs, helping to delineate the cognitive and corporeal coordinates by which subjects orient themselves in the field of social meanings.

In performing this function, BCAs often exhibit a peculiar temporality that is able to mediate between the central and unrelenting demands of capitalism—for constant growth, exploitation of workers, and the privatization of collectively generated wealth and resources—and the ongoing social strife, contradiction, and calamitous breakdown produced by capital’s everyday operation. This temporality, which is exemplified by The Force Awakens, is simultaneously anticipatory and nostalgic, revisiting formative past moments of exhilaration even while it projects these materials into shapes that help ensure the reproduction of the same, problematic tendencies that summoned critique and resistance in the first place. This is a mechanism that Jameson articulates when he describes how popular culture captures audience buy-in through utopian content in the form of both critique and camaraderie, only to redirect these potentially revolutionary energies back into forms of narrative closure that reify the dominant system (“Reification”). I have built upon Jameson’s model to show how the temporalities and spaces of contemporary capital impact the ideological function of popular narratives, allowing popular culture to work akin to the kinds of scenario planning strategies by which states and capitalists attempt to steer geopolitics in directions that favor their interests (Orpana “Freedom,” “The Law”). To further elucidate this mechanism here, I will first turn to the original Star Wars film from 1977 to consider the ways in which tensions inherent in the Fordist compromise were captured and then re-contained through narrative means. This will provide the foundation for a consideration of how The Force Awakens reworks and reproduces a similar act of interpellation for a new generation of viewers.

Rescuing the Princess from Fordist Technocracy

Authors like Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy, David Harvey, Michel Foucault (The Birth), and Jeremy Gilbert have described the conjunction of factors that led to the rise and consolidation of neoliberalism over the past several decades, and it is not possible here to go into detail about the trajectory taken by this transition. However, one central factor of the shift to neoliberalism that pertains to the Star Wars films is the mounting demands put upon industrial capitalism by women and racialized minorities to have their work in the service of social reproduction recognized and compensated. In his book In Letters of Blood and Fire, George Caffentzis points out how the male wage that supported the Fordist compromise was buttressed by the unpaid reproductive work of women and underpaid minorities in the service sectors. Demands for equity and recognition from these groups in the 1960s and 70s helped precipitate a crisis in the Keynesian social order (24-44). Mounting pressures on the industrial system were amplified by a new generation of relatively affluent, middle-class youth who demanded meaningful work that went beyond the ascetic, disciplinary “iron cage” of factory employment. This confluence of societal critiques and demands, as evidenced in the new social movements and counter-cultural energies of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, produced a generational gap in social expectations for many Western youth, whereby the stable but routine employment of the Fordist era was cast under a pall, and the world of both work and culture was imbued with new, libidinous energy and expectations. It was in the crucible of these mounting forces that the neoliberal capitalist order emerged, one which aggressively set about implementing a more unstable and predatory relationship between capital and labor, whereby the younger generation’s demands for meaningful work was granted, but at the expense of dismantling and privatizing much of the social wealth that was secured by workers’ struggles throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

We can read the BCA of the Death Star from Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) in light of these shifts. As a condensation of the kinds of disciplinary, instrumental rationality, and repressive, masculinist hierarchies associated with industrial capitalism, the Death Star with its legions of obedient Stormtroopers, officers, and technicians, and haunted by the lurking, patriarchal figure of Darth Vader provides a symbolic representation of Fordist, technocratic society itself. Against this menace, a rag-tag band of rebels from the liminal margins of the galaxy must locate the chink in the armor that will bring down the technological goliath. Before doing so, they must rescue the symbol of social reproduction, in the person of Princess Leia, from her capture by the system, returning her to a place of leadership in the newly emergent world order. This narrative fits with the trajectory of generational discontinuity sketched above: exciting, multi-species diversity and gritty, proletarian authenticity provide a backdrop for the young, white protagonists’ struggle against a technocratic monolith, and these heroes emerge triumphant under the sign of equality and diversity, with a Princess as their figurehead.

If A New Hope helped give expression to some of the transformational energies that shaped the decades of transition between the residual Fordist and the emergent neoliberal orders, providing an apparatus that interpellated a new generation of workers into the dawning, post-industrial society, The Force Awakens must perform a similar operation, several decades later, for a new and more diverse, precariously situated generation of middle- and working-class subjects. From this perspective, the film registers a number of social tensions related to the progressive dismantling of collective resources, the corralling of proletarian struggle and the reproduction of capitalist relations of exploitation for a new generation of Western viewers who, unlike their parents, are likely to have had only limited and circumscribed experiences of hopeful moments when it seemed as though the rebellion might be winning. One might note, for instance, the downgrading of the “rebel” forces from the original trilogy into an organized “resistance” in The Force Awakens, a shift that registers the way in which globalized capitalism itself has lost its outside or circumference, thus recasting social struggle in a more post-structuralist articulation that celebrates internal friction and “lines of flight” over outright competition between different modes of production. Perhaps in compensation for this unsettling of what formerly seemed to be relatively stable (if intolerable, for many subaltern subjects) coordinates by which identities were determined in the socio-political order, the more recent film also exhibits an amoral dualism, in which the mythology of “keeping balance within the Force” is expressed through metaphors of light and darkness rather than the explicitly moral terms of good and evil foregrounded in the original trilogy. Recall Luke’s words to the dying Darth Vader, in Return of the Jedi: “There is still some good in you, I can feel it.” In contrast, when Han Solo confronts his troubled son, Kylo Ren in The Force Awakens he says, “there is still some light in you.” This subtle shift is a break from the moral relativism regarding the Force that informs the original trilogy and prequels, where the seemingly absolute difference between the Sith and the Jedi Order is complicated by hints regarding their mutual implication, but where overarching concerns about morality and salvation (both personal and collective) remain intact. The Force Awakens translates this dynamic into the more ambiguous and amoral language of light and darkness.

Another BCA by which the film addresses post-Fordist social realities is provided by the broken family unit of Han Solo and Leia Organa whose offspring, Kylo Ren, has sided with a nascent, totalitarian organization in a manner that evokes contemporary fears over the radicalization of Western youth by various fundamentalisms. In the film, anxiety over fundamentalism takes the Orientalized form of the “Knights of Ren” and their imbrication in the neo-Fascism of the First Order. As a mode of interpellation, the intergenerational dynamic between Kylo Ren and his parents calls out to a generation of youth who have experienced considerable shifts in the norms pertaining to the nuclear family reinforced by the industrial, Fordist order. It is telling that the dissident posture of Han and Leia’s generation of rebels manifests, in their offspring, as an exotic fundamentalism whereby Kylo Ren nostalgically identifies with the Oedipal dimensions of the residual, industrial society. This detail registers, in the guise of fantasy, what is actually occurring in our contemporary political context, where the fragmentation and retreat of social agents into various siloed and privatized enclaves makes the project of working towards collective goals (other than those organized by the market) extremely difficult. The BCA of Kylo Ren’s radicalism here works as a distorting lens that casts any resistance to the actual, dominant, global order in the guise of archaic fundamentalism. At the same time, the link drawn between Ren’s radicalization and his nostalgia for the past, technocratic order (symbolized by the fetishized relic of Darth Vader’s mangled helmet) tellingly points to the disavowed fundamentalism of the contemporary capitalist economy itself, which couples a superficial commitment to tolerance and diversity with the production of racialized, militant adversaries who are depicted as stubbornly refusing to become modern subjects. If there is a chink in the ideological armor of the film, it is here, where the figure of Kylo Ren points towards the hidden, real-world complicity between a totalizing market system and the fundamentalisms that only appear to oppose it. As I further articulate below, it is this disavowed totality of the global market which must be displaced and condensed into the successive iterations of the Death Star or super weapon, the repeated vanquishing of which by the rebels/resistance does not so much overthrow the dominant order as guarantee its reproduction for a new generation of subjects.

Pastiche Squared: Attack of the Memes

In The Force Awakens, audience identification with Rey and Finn provides a vehicle by which new and old viewers are (re)interpellated into the fixtures of the Star Wars universe. If the 1977 film offered a form of white-washing whereby subaltern energies related to ethnic, gendered, and proletarian struggles were captured and redirected via an all white main cast (with the illustrative exception of James Earl Jones as the voice of “the man in black”), then The Force Awakens squarely addresses this issue: a racialized former janitor for the First Order and a courageous, technologically astute woman take the lead of the resistance. However, whereas seeing Han and Luke, in 1977, battle tie fighters from the gun stations of the Millennium Falcon allowed young (largely white, male) viewers to directly identify with these heroes and so project themselves as engaging in the same, fantastic battle, the 2015 film provides an added frame that signals historical distance from the founding moment of the original film: we identify with two characters stumbling upon a version of the same thrilling adventure that audiences experienced in 1977, thus keeping the original alive in a way that a wholly new plot line would not have allowed.

If, as Fredric Jameson recognized in 1984, the original Star Wars films are examples of postmodern pastiche that draw from prior cultural forms such as the western and early sci-fi pulps, then The Force Awakens offers pastiche of pastiche, the double framing working to both gesture to and neutralize historical distance from the “original” postmodern event (Postmodernism 17). This reading reinforces Thomas Elsaesser’s astute observation that, “Earlier than any other studio, the Disney Corporation had ‘realized’ that the modelling—and marketing—of time is cinema’s deepest fantasy” (21-22). Disney’s purchase of the Star Wars franchise from Lucasfilm in 2012 for $4 billion supports Elsaesser’s observation about Hollywood’s desire to colonize time, history, and collective memory through aggressive marketization. Along with its 2010 purchase of the Marvel comic book franchise, Disney has consolidated ownership over the intellectual content that shaped the childhood mythologies for many Western subjects from at least the 1960s (a date that can be pushed back much earlier if we consider Disney’s appropriation of Grimm’s fairy tales and other folklore). The interpellative framing of The Force Awakens reinforces Disney’s strategy, playing upon millennials’ nostalgia for a cinematic moment they never directly experienced, but which has been filtered through transmedia and the formative pop cultural experiences of previous generations.

This intergenerational interpellation helps build and maintain a fan base, and perpetuates the lucrative market for Star Wars merchandise, but how does the corporate management of time and memory affect the narrative structures upon which these marketing strategies depend? In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of its Real Subsumption under Capital,” Nicholas Brown suggests that pop cultural artefacts, like blockbusters, are not so much films as collections of memes arrived at through market research and designed to satisfy specific commodity niches. Given contemporary modes of production, argues Brown, more traditional interpretive codes and questions about intentional meaning—which presuppose authorial agency—are not adequate to the task of understanding pop cultural texts like The Force Awakens. The discipline of Cultural Studies’ emphasis on the politics of the production, distribution and consumption of popular culture offers alternatives to modes of interpretation grounded in authorial agency. For instance, Brown’s analysis can help distinguish between The Force Awakens and the less successful “prequels” made by Lucasfilm between 1999 and 2005, before its sale to Disney. Though the three prequels elicited mixed reception, they did exercise a modicum of authorial vision and explore terrain that was different from the original trilogy (of 1977-1983). The prequels, for instance, detailed the interesting dynamic of corruption, decadence, and fanaticism within the Jedi Order itself, subtly implying that Anakin’s transformation into Darth Vader did not constitute a contradiction of the Jedi Order so much as its necessary consequence. Slavoj Žižek takes this plot element a step further, arguing that Anakin’s excessive commitment to his mother and his lover, Padmé—the “attachments” that make him vulnerable to seduction by Palpatine and the Sith—actually make him “the only true subject of the Star Wars sagas” (The Parallax 102). Though Žižek criticizes Lucas for not fully realizing this thread of the narrative—“that Vader is [actually] a good figure, a figure which stands for the “diabolical” foundation of the Good”—its lineaments are present in the narrative of the prequels and original trilogy (103). Contrast this to The Force Awakens, where such considerations are hinted at but largely re-contained in the figure of Kylo Ren, the aberrant son who succumbs to fanaticism despite the tutelage of the now vanished Luke Skywalker. It would have been interesting to further explore the intergenerational dynamics that lead to Ren’s allegiance to Snoke and the First Order (celebrity parents? familial breakdown? disappointed revolutionary hopes?), and perhaps coming instalments of the franchise will delve into these issues. Regardless of the turn that future Star Wars films might take, one wonders if it was at least partly the attempt on Lucas’s part to exercise authorial vision that soured fans to the prequels: to the extent that these films raise questions about the imbrication of empire, politics, culture, and religion, they offer the possibility for critical engagement that goes beyond the largely symptomatic readings that an artefact like The Force Awakens solicits.

Echoing Brown’s insights into the lack of authorial determination in contemporary pop culture, Žižek characterizes the Star Wars saga as a political myth to the extent that it “is not so much a narrative with some determinate political meaning but, rather, an empty container of a multitude of inconsistent, even mutually exclusive, meanings . . . its ‘meaning’ is precisely to serve as the container for a multitude of meanings” (101). Interestingly, Žižek identifies the story of how “Anakin the human individual is interpellated into the subject of Darth Vader” as the central, politically progressive element of the franchise, even though this theme, in Žižek’s estimation, has not been adequately addressed by the films (103). In contrast to the unrealized potential for interpellating revolutionary subjects detected in the Star Wars films by Žižek, my analysis reveals how audiences and fans are being interpellated into a set of practices, affects, and ideological structures with specific contents that pertain to the perpetuation of capitalism in the post-Fordist era. But what are these specific ideological contents? Star Wars emerged at the juncture of three important historical moments or tendencies. First, A New Hope (1977) helped signal the dawning of the age of the Hollywood blockbuster or “event” film. Breaking box office records and setting new precedents for merchandising and ancillary revenue streams, the film’s “Long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” actually forecasts the form that blockbusters would take for decades to come. In this regard, note the nostalgic/anticipatory temporality the film’s epigraph performs: the events depicted are from long ago and far away but also of the future and present, a kind of dream realm linked to immediate, real world circumstances through a series of disguises, displacements, and projections. It is this temporal disjuncture that allows the franchise to span generations, reworking its materials in ways that speak to new generations of fans, while keeping central elements of its ideological message intact.

Second is the appropriation and recombining of older cultural forms, mythological materials, and narratives tropes into a marketable franchise over which a private, Hollywood studio maintains exclusive control. The Star Wars franchise, long before its purchase by Disney (who yet remain the masters of this strategy), constitutes a keystone example of the privatization of the commons: the enclosure of common cultural material by private enterprise for the purpose of securing future profit, audiences and monopolies. Henry Jenkins provides critical analysis of the ways studios like Disney and Lucasfilm have used copyright law to corral and monopolize the cultural commons. He points out how copyright legislation originally designed to protect authors and encourage innovation has, with such legislation as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, been

rewritten to reflect the demands of mass media producers—away from providing economic incentives for individual artists and toward protecting the enormous economic investments media companies made in branded entertainment; away from a limited duration protection that allows ideas to enter general circulation while they still benefit the common good and toward the notion that copyright should last forever; away from the ideal of a cultural commons and toward the ideal of intellectual property. (141)

With the interests of media giants like Disney at the center of such changes, the famous vehicle of underdog space pirates Han Solo and Chewbacca is literally enclosed and privatized by legislation that shares its Millennial name.

Thirdly, as this essay has underscored, the first Star Wars films emerged at a crucial historical junction whereby the post-World War Two Keynesian welfare state, which provided subjects some insulation from the savage competition and deskilling of the market, was being challenged and disassembled to make way for the neoliberal, global capitalism that has become hegemonic over subsequent decades. It is in light of this shift that the narrative of Star Wars becomes most intelligible: by asserting the values of friendship, loyalty, and diversity—embodied in the rebels as a rag-tag group of comrades—against a cold and pitiless technocracy, the franchise provides a compensatory image of social cohesion at the very moment when aggressive neoliberal restructuring was challenging any and all forms of collective identity that did not conform to the needs of the marketplace. Here, the utopian content of the narrative is in stark contrast to the values and practices (of privatizing of the commons, colonizing time and memory) of the political and economic context that the film itself exemplifies. In reacting to its own real-world context, the narrative’s fantasy helps manage symptoms of alienation and desire for alterative formations, even while the production, distribution, and merchandising mechanisms of the franchise help ensure these symptoms do not subside. To accomplish this ideological effect, a further twisting of form and content, context and narrative is necessary, and this takes the form of a symbolic representation, within the saga’s own narrative, of the socio-political-economic context to which the films are reacting.

Biopolitics Writ Large

Star Wars transposes capitalism’s imperative to growth and privatized appropriation into the technocratic register of what was actually the heart of Keynesian principles of societal stewardship by a cadre of trained specialists: the Death Star(s) resemble(s) nothing so much as the modern factory on a planetary scale, and the blowing up of this image of totality—three times now—by the rebels can be read, not as a challenge to the smooth functioning of markets, but as removing the governmental and institutional barriers that neoliberal ideology identifies as impeding them. As a BCA, the Death Star neatly condenses an entire complex of practices and power relationships related to biopolitics, or the modern strategies for the regulation and governance of life itself in increasingly comprehensive and intensive ways. A literal destroyer of worlds, the Death Star (and its reiteration in The Force Awakens as the “Starkiller Base”) gestures towards the biopolitical threshold identified by Michel Foucault as a development of human capacities that puts the existence of human life itself under question (The History 41). During the 20th century, as technological and market structures became more refined, the capacity of these apparatuses for steering and controlling human life expanded. These developments were justified as essential to perpetuating modern consumer lifestyles while simultaneously being accompanied by mounting unease and critique over the scope and intrusiveness of these structures. The ISAs identified by Althusser were part of a biopolitical, technocratic order that, during the Fordist era, helped ensure the reproduction of a healthy and disciplined workforce, but which also was attended by such bugbears as nuclear armaments and the threat of global destruction exacerbated by the cold war. Struggles over the redefinition of sites of ideological reproduction that began in the 1960s and 70s tried to open escape routes from the repressive aspects of bio-technocratic control, but these were largely re-contained by the BCAs that began to proliferate as a means for societal reproduction in the neoliberal era. In short, the shift in emphasis from ISAs to BCAs allowed for the continuation of biopolitical forms of control while casting off much of the state infrastructure that guarded the reproduction of capitalist relations during the Fordist era. We can thus read the demolition of the Death Star at the end of A New Hope (and again in Return of the Jedi), not as a liberation from capital, but as the “creative destruction” of state apparatuses that accompanied neoliberal restructuring: though many of the state apparatuses were renegotiated, the capitalist ideology remained, now cast into the form of biopolitical apparatuses that used culture and narrative to perpetuate dominant ideas, relationships and values.

This reading makes intelligible a strange formal hiccup from the end of A New Hope, one that might otherwise be dismissed as merely related to the history of film’s roster of representational tactics. It has been observed that in the last scene, when Luke, Han, and Chewbacca are honored by Princess Leia in recognition of the service they have done the rebellion after blowing up the Empire’s Death Star, George Lucas borrows from the graphic vocabulary of Leni Riefenstahl’s Fascist documentary, Triumph of the Will (1935). In his book, The Making of Star Wars, J.W. Rinzler explains how a “minor controversy the press got hold of was the rumor that Lucas had deliberately used Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935) for the throne room scene” (“Haunting Hawaii”). Rinzler then cites Lucas’s disavowal of any conscious modeling of the scene upon Riefenstahl’s film:

The truth of that particular situation is that I hadn’t seen [Triumph of the Will] for about fifteen years . . . I had wanted to see it again because, early in the writing process [of A New Hope], I was thinking of doing a scene with the Emperor on the Empire planet, and I wanted to do that like Triumph of the Will. But it unfortunately got published that I was going to try to see Triumph of the Will and use it in Star Wars; evidently somebody read that somewhere and then looked at the end of the movie and thought that looked just like Triumph of the Will. But the end of the movie is just what happens when you put a large military group together and give out an award. (qtd. in Rinzler, “Haunting Hawaii”)

Despite Lucas’s dismissal of the striking similarity of the staging of the throne room scene to the composition used in Triumph of the Will, that Lucas should, intentionally or not, borrow devices from a film celebrating Hitler’s rise to military power in 1935 is not surprising: Riefenstahl’s film has been celebrated and emulated for her novel use of cinematography to produce effects of state grandeur and solemnity, and the fact that these techniques were first used in service of a Fascist regime does not necessarily disqualify their value at a purely formal, artistic level. Or does it? Perhaps there is a short circuit between form and content here that goes beyond mere appropriation of Riefenstahl’s techniques, one that echoes the mutual reinforcing of form, ritual, and content at work in ideological interpellation.

If the Death Star aesthetic with its sleek corridors, bright control panels, polished floors, and yawning chasms provides a visual hieroglyph for the bio-technocratic centralism of the Fordist era, and if the destruction of the same by the rebel heroes at the end of A New Hope actually signals a clearing away of perceived impediments to the operations of the market in a globalized context, then perhaps the denouement that immediately follows, framed as it is by a graphic vocabulary borrowed from Fascist documentary, actually reveals something of the political unconscious of the Star Wars franchise. Similar to the way many of the countercultural energies of the 1960s and 70s—for diversity, inclusion, non-conformity, personalized expression, job satisfaction, self-actualization, and so on—were deftly coopted by neoliberal market structures (such as niche marketing, divide-and-conquer politics, reactionary populism, precarious employment), so too does the fascist graphic vocabulary from the end of A New Hope gesture toward a secret complicity between the utopian vision of resistance championed by the Star Wars franchise and the totalitarian tendencies of contemporary market societies. Viewed from the perspective of the historical unfolding of possibilities for collective freedom and political agency (Jameson, The Political 1-7), the Star Wars films provide a site—what I have called a BCA—for the managing and re-containment, through narrative and embodied practices, of contradictions and dissenting energies that emerge in the course of the everyday operations of contemporary capitalism.

Perhaps it is this co-dependency, between the seemingly informal, insurgent and organic order of the marketplace and its disavowed dependence upon a simultaneously suppressed but necessary totalizing structure that requires the Star Wars films to repeatedly produce more and bigger Death Stars for the always-embattled resistance forces to destroy. This BCA would be in keeping with the tendency, chillingly described by Ian Bruff in the European context as “authoritarian neoliberalism,” to buttress police and military state structures while renegotiating reproductive social institutions like education, social security, unionism, and health care into more aggressively coercive forms (rather than garnering tacit consent). The neoliberal ideology of small government/big markets covers over the way in which the state has actually been significantly amplified and deployed by neoliberals, who rely upon states functioning as guarantors of the security and fluidity of international market relations. In this context, the spherical, planetary battle stations from Star Wars appear as a return of the repressed element of governmentality that the capitalist system cannot do without, even while it purports to transcend and minimize such structures. Interestingly, it is only in the largely unpopular prequels that a spherical image of totality is absent as a nemesis to be dispatched. In the prequels, the spheroid is graphically repeated in the seating design of the Senate Chambers of the Galactic Republic where the fate of the Galaxy is politically managed, and where Emperor Palpatine and Yoda have their dramatic light sabre duel (Star Wars: Episode III).

By returning to the Death Star trope in The Force Awakens, could it be that Star Wars fans were simply not ready to confront the kinds of questions raised by the prequels regarding the shadowy complicity between justice and corruption, prohibition and desire, markets and militarization, not to mention the pressing question of what form a regenerated and egalitarian new Republic might take? As the third in a series of technocratic monstrosities, the Starkiller Base in The Force Awakens is interesting for the manner in which the super weapon is grafted to and continuous with the host planet, which thus becomes a kind of immense battery for concentrating “dark energy” that can produce a beam capable of destroying whole solar systems. Much like the operation of this death ray itself, the Starkiller Base condenses a whole host of real-world anxieties over the cumulative, hitherto backgrounded effects of globalized, industrial society, which is now threatened by the unintended by-products of its very success, from climate change, to mounting geopolitical unrest, to resurgent populist resentment and nationalism. Perhaps a glimmer of actual hope can be salvaged from these sensationalist, cinematic fantasies of totality insofar as they gesture toward capitalism reaching a terminal limit: no longer a detached, technological satellite, the latest Death Star is recast as a planet in its own right, symbolically registering a totality that economically inspired fantasies cannot possibly transcend, despite contemporary schemes for colonizing Mars.

Against such escape fantasies, a sober materialism is the admirable subtext of Garreth Edwards’s contribution to the franchise, Rogue One (2016). Rather than escaping the destruction of the Starkiller Base in space ships, as happens at the end of The Force Awakens, the heroes of Rogue One die at the close of the film, providing fitting figures for the kind of eventful disruption of the given order that is required if human life is to survive our current juncture. However, interpretation of these deaths in light of reflections upon mortality contained in the rest of the franchise reveals a transcendentalism at work that subtly informs the seemingly materialist stoicism of Rogue One. In contrast to the dramatic reversal by which Anakin Skywalker’s humanity is rescued from technocratic entanglement at the end of Return of the Jedi, Rogue One’s protagonists preserve their humanity by losing their lives. It is here, however, that I would offer an alternative to Žižek’s reading, already mentioned, of the unrepentant Darth Vader as the properly interpellated, political subject that Lucas (and Disney after him) has been unable to fully realize as the revolutionary subject at the heart of the franchise (The Parallax 101-103). Recall, instead, the acquiescence of Obi-Wan Kenobi to being slain by Vader at the end of the lightsaber duel with his former student in A New Hope. On one level, Obi-Wan’s surrender to Vader is an acceptance of the role he himself has played in creating a monster: the aging Jedi is atoning for his failures as a teacher, and the failings of the Jedi Order in general. Simultaneously, Obi-Wan’s sublime composure is presented as a performative, last instruction to Luke—an illustration of the power of the Force to transcend what only appears to be one’s perishable, mortal existence. Obi-Wan’s actions here are illuminated further by information, delivered by Yoda in Episode III, hinting that Obi-Wan’s own teacher, the maverick Qui-Gon Jinn, had discovered a pathway to immortality that provides an alternative to the necromantic combination of technology and sorcery deployed by Palpatine and the Sith to unnaturally prolong corporeal life. Self-sacrifice of the kind performed by Obi-Wan in Episode IV is thus the sign of a subject’s being fully interpellated into the salvific, life-supporting aspect of the Force, a moment that the antagonists of the saga attempt to avoid through various and gruesome, ultimately deforming and inadequate mechanisms. Though the protagonists of Rogue One are not Jedi trained in Qui-Gon’s technique of preserving consciousness after death, the finale of this film should not be mistaken for pessimism. Like the deaths of Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon, the sacrifice of Jyn and Cassian at the end of Rogue One illustrates the radical courage and fidelity required in the task of bringing about the changes necessary to rescue humanity, and the planet, from the ravages of global capital. And, like the spectral presences of the fallen Jedi who appear throughout the Star Wars saga, the protagonists’ deaths at the end of Rogue One likewise serve as a place-holder for the as-of-yet unimaginable new formation that awaits just the other side of the collective fog that currently clouds our ability to imagine a different and better future.

[The Author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this article for their input and edits, and Jason W. Ellis for patient and invaluable help sourcing film stills and the material from Rinzler’s book. This essay is expanded from a shorter reflection the author posted on the blog theoryawakens.wordpress.com on 21 January 2016.]

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays. Translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella, Stanford UP, 2009.

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” Cultural Theory: An Anthology, edited by Imre Szeman and Tim Kaposy, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, pp. 204-222.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty. Polity, 2007.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke UP, 2011.

Brown, Nicholas. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Real Subsumption Under Capital.” nonsite.org, 13 Mar. 2012,

http://nonsite.org/editorial/the-work-of-art-in-the-age-of-its-real-subsumption-under-capital. Accessed 9 Nov. 2017.

Bruff, Ian. “The Rise of Authoritarian Neoliberalism.” Rethinking Marxism, vol. 26, no. 1, 2014, pp. 113-129.

Butler, Judith. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford UP, 1997.

Caffentzis, George. In Letters of Blood and Fire: Work, Machines, and the Crisis of Capitalism. PM, 2013.

Deleuze, Gilles. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October, no. 59, Winter 1992, pp. 3-7.

Duménil, Gérard and Dominique Lévy. “The Neoliberal (Counter-) Revolution.” Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, edited by Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnson, Pluto, 2005, pp. 9-19.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “The Blockbuster: Everything Connects but not Everything Goes.” The End of Cinema as We Know It: American Film in the Nineties, Colombia UP, 2002.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978 – 1979. Translated by Graham Burchell, Picador, 2008.

---. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Edited by C. Gordon, Pantheon, 1980.

---. The History of Sexuality, vol.1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley, Vintage, 1978.

Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. Free, 1992.

Gilbert, Jeremy. “What kind of Thing is ‘Neoliberalism?’” New Formations, vol. 80-81, 2013, pp. 7-22.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. Empire. Harvard UP, 2000.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberailsm. Oxford UP, 2005.

Hicks, Wayne L. “When the Force was a Farce, Part Two.” tvparty.com, http://www.tvparty.com/70starwars2.html. Accessed 9 Nov. 2017.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke UP, 2003.

---. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as Socially Symbolic Act. Routledge, 1983.

---. “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture.” Social Text, no. 1, Winter 1979, pp. 130-148.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York UP, 2006.

Massumi, Brian. The Politics of Affect. Polity, 2016.

McKenzie, Jon. Perform or Else: From Discipline to Performance. Routledge, 2001.

Orpana, Simon. “Freedom 2044: The Temporality of Financialization and Scenario Planning in Looper.” Time, Globalization and Human Experience: Interdisciplinary Explorations, Edited by Paul Huebener, Susie O’Brien, Tony Porter, Liam Stockdale, and Yanqui Rachel Zhou, Routledge, 2016, pp. 68-86.

---. “The Law and its Illicit Desires: Transversing Free Market Claustrophobia and the Zombie Imaginary in Dredd 3-D.” The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, vol. 37, no. 4, 2014, pp. 298-319.

Reed, Philip. “Kenner’s Star Wars Death Star Playset in the 1979 Milwaukee Journal.” battlegrip.com, 31 March, 2015, http://www.battlegrip.com/kenners-star-wars-death-star-playset-in-the-1979-milwaukee-journal/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2017.

Rinzler, J. W. The Making of Star Wars. (Enhanced Edition), EPUB ed., Ballantine, 2016.

Rogue One. Directed by Gareth Edwards. Lucasfilm, 2016.

Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace. Directed by George Lucas, Lucasfilm, 1999.

Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones. Directed by George Lucas, Lucasfilm, 2002.

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith. Directed by George Lucas. Lucasfilm, 2005.

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. Directed by George Lucas. Twentieth Century Fox, 1977.

Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back. Directed by Irving Kershner, Lucasfilm, 1980.

Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi. Directed by Richard Marquand. Lucasfilm, 1983.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Directed by J.J. Abrams. Lucasfilm, 2015.

Triumph of the Will. Directed by Leni Riefenstahl. Leni Riefenstahl-Produktion, 1935.

Žižek, Slavoj. In Defense of Lost Causes. Verso, 2009.

---. The Parallax View. MIT P, 2009.