Thee Megan Movement: Defining and Exploring Hot Girl Rhetoric

by Ebony L. Perro

Published June 2022

Abstract:

This article argues that through defining and designing hot girlhood, Megan Thee Stallion constructs hot girl rhetoric, a lexicon of ratchet resistance that confronts patriarchal norms and galvanizes fans to eschew respectability politics. Framing Megan’s rhetoric in the context of ratchet imaginaries, the article also argues that Megan and her rhetoric disrupt the ratchet/respectable binary. Through analyzing the use of phrases like “hot girl,” “hot girl summer,” “real hot girl shit,” and adjacent language in media authored by Megan and her fanbase, the article identifies principles of hot girlhood. Finally, it traces an arc of hot girlhood through songs that directly invoke the terms (e.g., “Hot Girl,” “Hot Girl Summer,” and “Girls in the Hood”), demonstrating how the music embodies the principles outlined in Megan’s definition of hot girlhood.

Keywords: Megan Thee Stallion, hot girl, ratchet, rhetoric, pop music, rap music

Over two decades after New Orleans rappers the Hot Boys reductively defined the term “hot girl” in their song “I Need a Hot Girl,” Houston rapper Megan Thee Stallion redefined hot girlhood by centering women’s voices and experiences. However, Megan moved beyond redefining hot girlhood; she created a lexicon for empowerment. Though not everyone readily understands the value of hot girlhood and its accompanying language, Megan’s rhetoric is part of a lineage of cultural work performed by Black women in hip hop. She problematizes one-dimensional readings of Black womanhood and generates a language for her fanbase to challenge oppressive ideologies. While many artists contest (and ignite) discourses about Black women, Megan Thee Stallion’s hot girl rhetoric generates cultural phenomena that disrupt the respectable/ratchet binary for Black women. While Megan’s message draws from Black women’s experience and primarily attracts Black women listeners, her message reaches women of all races and encourages them to defy patriarchal constructions of womanhood.

Megan presents her music and visual media as guidebooks for pleasure-seeking. Her rhetorical strategies, underscored by ratchetness, provide a hot girl glossary for talking shit. The Crunk Feminist Collective redefines ratchet, typically associated with sexist, classist ideas about Black women, as “a mode of both play and resistance that is unconcerned with social propriety,” often revealed through unapologetic engagement in “profane social behaviors” and refusal to aspire to respectability (Cooper et al. 327). Megan's use of language aligns with Michelle Megss’ concept of “ratchet womanism;” her vernacular “become[s] a master class in how to dismantle respectability and reject the shaming from asserting agency over your body” (64). Megan’s rhetoric evokes images of self-reliant, self-governing, sex positive women. Her rhetoric rejects anti-black connotations of ratchet and favors what Brittney Cooper terms disrespectability politics or “acts of transgression that Black women can use to push back against too-rigid expectations of acceptable womanhood” (Cooper et al. 223). Much like Cooper, who asserts that ratchet feminism critiques misogyny and sexism in “ratchet spaces,” Megan resignifies ratchet. The Black women communities connected by her rhetoric embody the second tier of ratchet feminism: friendship between Black women whose performances of Black womanhood are read as low class (Cooper et al. 213). Megan’s evocative language generates agentic, communal hot girl rhetoric and hot girlhood principles. These principles—being free, confident, unapologetic, and seeking joy/pleasure—lead fans, particularly Black women, to a hot girl praxis through which they perform the personal and political work derived from actualizing these principles.

Megan Thee Stallion’s discography and the responses to her body—and body of work—reflect her reclamation of ratchet. With her mixtape Rich Ratchet (2018), songs like “Ratchet” from Fever (2019) and “Savage” from Suga (2020), Megan weaves ratchetness through her oeuvre. Her work troubles negative meanings of ratchet—wielded against Black women who fail to be respectable. Bettina Love notes that because of the "narrative landscape of popular culture, adherers to respectability politics coded [Black women] as “loud,” “hostile,” and “reckless” (540). Using ratchetness—which, according to Amoni Thompson-Jones, “exca[vates] a language of Black girl refusal” that defies patriarchal norms (87) Megan’s “loudness”—serves a strategy to combat silencing. Her rhetoric situates her among feminists and womanists who develop language to articulate their experiential truths. As Megan celebrates ratchetness, her work—placed in conversation with scholars who assert ratchetness as a means of emancipation—adds to Black women’s discourses on agency. Therí Pickens, Bettina Love, and L. H. Stallings, for instance, discuss ratchet imaginaries as challenges to respectability politics. Pickens notes that ratchet imaginaries are not concerned with narratives of social uplift and racial progression. Pickens also writes that ratchet “functions as a tertiary space in which one can perform a racialized and gendered identity without adhering to the prescriptive demands of either” (44). Megan operates within the ratchet imagination, problematizing the ratchet/respectable binary and prescriptive roles of Black women through her subversion/inversion of gender dynamics. She rejects the imposition of white/male/classist constructions of Black women. Just as L.H. Stallings argues that the Black Ratchet Imagination “lead[s] others to create something more ‘useful’ in other transitional spaces” (Stallings 136), Megan’s hot girl rhetoric leads Black women to embrace their “performance of the failure to be respectable” (136). Megan supports these failures through her definitions of hot girl/hot girl shit and the principles of hot girlhood that arise from these definitions and her music.

“Real Hot Girl Shit”: Defining “Hot Girl”

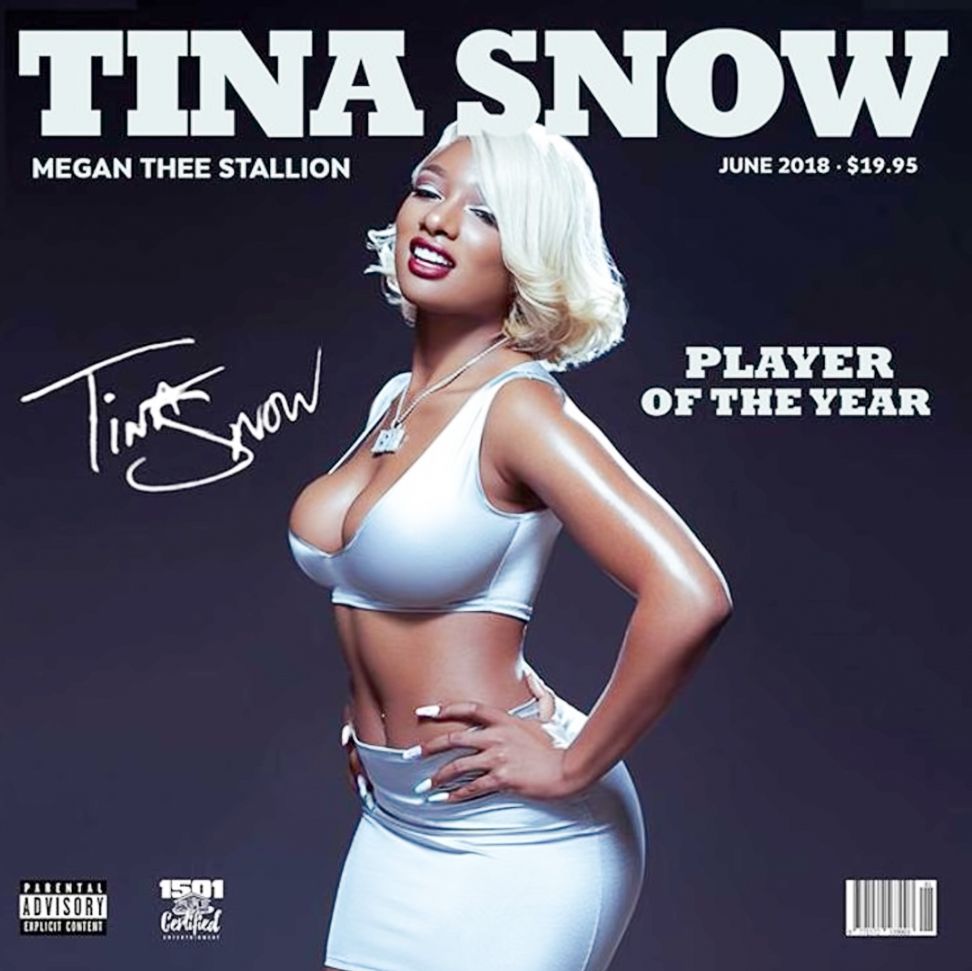

Although early uses of "hot girl" in her first mainstream mixtape, Tina Snow (2018), did not garner the same attention as recent presentations, the growing popularity of the phrase led Megan to define “hot girl” across mediums in 2019.

Taking to Twitter to explain hot girl/hot girl shit, Megan stressed self-representation, arguing that “real hot girl shit=being free and unapologetically you, showing off your confidence, hyping up your friends, not taking shit from nobody etc” (@theestallion). A few months later, she further explained that “Being a Hot Girl is about being unapologetically YOU, having fun, being confident, living YOUR truth, being the life of the party etc” (@theestallion).

Her inclusion of “etc.” in her tweets leaves space for hot girls to self-define. Her tweets articulate hot girlhood principles (being free, unapologetic, confident, and seeking joy) that are woven through her lyrics and adhered to—and expanded upon—by her followers.

As the discourse surrounding hot girlhood evolves, her fans assist with this evolution. She invokes a hot girl diaspora, creating interpretive communities primarily through hashtags and music. Across the globe, Black girls, Black women, and people across various identities channel their inner hot girl. This dispersal, attributed to her language, creates varying iterations of hot girlhood. Opposers often frame hot girlhood as promiscuity and fail to see the nuances of the term, solely basing it on Megan’s sex positive persona. These responses to hot girlhood are often veiled objections to women’s empowerment and self-definition that run counter to social constructions of respectable womanhood. Her fanbase creates and combats definitions of the catchphrase. In a viral tweet from the inaugural hot girl summer in 2019, for instance, a Twitter user asserted, “Niggas just ASSUMED hot girl summer was a hoe summer. Just like niggas.. always jumping to conclusions. Hot girl summer is just girls knowing our worth and doing what we want. But y’all don’t wanna hear that tho” (@AnnieNickens).

Responding to misogynistic discourse, she rearticulates the meaning of hot girl summer against a politics of sexual respectability. By alluding to women’s right to experience the joys of hot girl summer and “clapping back” at men, she engages disrespectability politics to push back against men synonymizing hot girl and hoe. Her tweet addresses men’s presuppositions about hot girls based on their assumptions about Megan and her followers. @AnnieNickens defines and defends Megan’s lexicon while positioning men who critique hot girl summer as strategically deaf to Black women liberating themselves from narrow, anti-black constructions of womanhood. Her tweet makes it clear that hot girls demand respect from others, regardless of people’s assumptions about their choices.

Another notable example that unsettles the rachet/respectable binary comes from 16-year-old activist Marley Dias. Dias defended Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B after a host of conservatives demonized them for their song “WAP.” Dias crafted an Instagram post condemning respectability politics:

I’ve been mentioned as someone who is going to influence our young females to ‘grow up with dignity and not become a disgrace to society’ while Megan and Cardi were described as ‘back alley trash’ and ‘disgraces to society’…NEVER will I tolerate this misogynoir, any celebrations of my success should not be at the expense of other successful women.” (@iammarleydias)

Dias then tweeted out the message, adding, “Hot girls stand up for what’s right. Respect the humanity of ALL Black girls” (@iammarleydias). Her hot girl rhetoric hypes up Black girls and talks back to people who bolster respectability politics and engage in misogynoir—defined by Moya Bailey as “anti-Black racist misogyny that Black women experience, particularly in US visual and digital culture” (1). In her condemning of misogynoir, Dias demonstrates how Megan’s vernacular creates community, honors agency, and encourages respecting women and girls regardless of how they perform girl/womanhood.

With social media as a repository for the documentation, critique, and application of hot girlhood, (counter)narratives of Black women embracing ratchetness are highly visible and non-Black women seeking pleasure are highly visible. Vox contributor Rebecca Jennings cites fan definitions of hot girl summer from Vice UK. The responses show how Megan’s rhetoric generates principles of hot girlhood: “Girl, it’s hoe szn. Period. What makes a hot girl summer? Your attitude and your vibe. It’s 2019—a year for women to do what they want to do,” and “It’s about being a bad bih and role reversal—live your best life. Guys always talk about getting girls, and we love Meg because she’s doing exactly what they do unapologetically…” (Jennings). These representations focus on women’s autonomy, challenging gendered dichotomies that create power imbalances and baseless measures of human value. The broad spectrum of hot girls blurs the lines between respectable and ratchet and makes visible the tertiary space of the rachet imagination posed by Pickens. Though the examples embrace “hoe szn,” they still reject misogynistic conception of the term and speak to myriad ways language is resignified and reclaimed through hot girl principles. The responses show the term’s elasticity and the ways women unapologetically rebel against double standards.

Fans also demonstrate less direct rejections of and confrontations with respectability politics. Many hotties use the language of hot girlhood to engage their online community and put Megan’s cultural work, particularly her work on joy and freedom, into practice in their lives. Many refer to themselves as hot girls and champion hot girl activities but demonstrate that those activities are not always overtly sexual. During “quarantine summer,” Megan’s music dominated Tik Tok challenges. “The Savage Challenge,” where women embraced their complexities and claimed to be “classy,” “bougie,” and “ratchet” (Megan Thee Stallion, “Savage”), displayed Megan’s breaking of ratchet binaries. Another viral challenge, inspired by the intro to “Girls in the Hood,” but primarily popularized by white girls, “I Can’t talk right now, I’m doing hot girl shit,” offered a humorous spin on hot girlhood by framing mundane tasks as hot girl shit. The challenge asserts the “etc.” presented in Megan’s tweets. On social media, hot girl shit ranges from taking naps and watching Netflix to ignoring toxic exes and getting promotions. We can understand these Tik Tok challenges through Regina Duthley’s illuminating arguments about how the digital age extends the reach of hip hop discourse. She discusses digital wreck, a Black feminist form of resistance that responds to oppression, noting that the digital era simplifies engagement in subversive rhetorical acts and “expand[s] the hip-hop rhetorical tradition to the contemporary new media age” (202). Using this viral/mimetic terminology, we can see that Megan brings digital wreck that contributes to the Black Ratchet Imagination in new ways (e.g., trademarking hot girl summer and marking literal ownership of her language). Her fans and followers, namely Black women, engage in digital wreck by showing the many variations of hot girl, using them to expand normative notions of Black womanhood.

Talk Yo Shit: Hot Girl Rhetoric and the Principles of Hot Girlhood

Megan’s music adds layers to the definition of hot girl. She uses her music to assert her identity and validate the experiences of fellow hot girls. Her music demonstrates to women that being a hot girl is a means of resistance with objectives of freedom, confidence, and joy. Through her “shit-talking,” she engages bell hooks’ notion of talking back. For Megan, “It is that action of speech of ‘talking back,’ that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of [Black women’s] movement from object to subject—the liberated voice” (hooks 9). She talks back to the heteropatriarchy and misogynistic rappers, and as she “speaks,” her lyrics reflect the principles outlined in her tweets.

In addition to establishing being unapologetic as a pillar of hot girlhood, Megan’s rhetorical choices illuminate the utility of hot girl rhetoric in doing freedom work. Her sampling of Eazy-E’s “Boyz-in-the-Hood” illustrates how hot girlhood “talks back.” In addition to sampling the beat and riffing off Eazy-E’s flow, the songs’ bridges are parallel. Eazy-E raps, “Cause the boys in the hood are always hard…Knowin’ nothin’ in life, but to be legit” (“Boyz-in-the-Hood”), while Megan raps, “Cause the girls in the hood are always hard…Knowin’ nothin’ in life, but I gotta get rich” (“Girls in the Hood”). By revising the song for girls, Megan uplifts the women objectified in/by the original rap. She uses her signature phrases to tell her story of empowerment, this time specifically for/from women in the hood. A review of “Girls in the Hood” by Sheldon Pearce suggests the personal and political work of her music: “It feels like Megan is leading a revolt of the women mistreated in rap songs” (Pearce). With hot girl rhetoric at the center of Megan’s revolt, hot girlhood becomes a palimpsest to overwrite problematic narratives of Black women. In his song, Eazy-E grabs a woman by her weave; contrastingly, Megan raps about her “thirty-inch weave” (“Girls in the Hood”). Once again embracing ratchetness, she ‘outright reclaim[s] and repurposes the original for those it disenfranchised’ (Pearce). The reclamation adds layers to hot girlhood and demonstrates her critiques of misogynoir and her centering of marginalized girls and women. With this sample, Megan articulates the ways hot girls unapologetically flip the (social) script.

Emphasizing women’s agency, Megan’s rhetoric leads a charge for liberation. Outside of the hot girl diaspora, the criticism surrounding Megan’s ideas of freedom often frames her as hypersexual, leaning into the image of the Jezebel. However, Megan and her followers rebuke these criticisms. Her explanation of the lyrics of “B.I.T.C.H,” a song that samples Tupac’s “N.I.G.G.A.,” coincides with the liberation motifs in her music. Megan has said, in reference to her lyrics, “Personally, I feel like when you a woman, people be trying to put them restraints on you. Like, ‘Oh you should behave this way, and you should do this’ because this is how society feel like women should be” (Genius). She ignores the judgment of others and defies expected performances of womanhood.

“Hot Girl Summer” demonstrates the autonomy reflected in this explanation and in her tweets. Peppered with allusions to agency, “Hot Girl Summer” illuminates a season of self-sovereignty, explicitly framed through lines like “ain’t no taming me” (Megan Thee Stallion). Megan’s language implies the rejection of women’s domestication and submission; again, she shows hot girl rhetoric as a mode of resistance. The resistance work continues with “Girls in the Hood.” Beginning with the proclamation, “fuck bein’ good, I’m a bad bitch / I’m sick of motherfuckers tryna tell me how to live,” the song captures Megan’s frustration with people’s denial of her right to self-expression. With this song she reopens her hot girl guidebook. The chorus opens with, “I’m a hot girl, I do hot shit / Spend his income on my outfit” (Megan Thee Stallion). Doing hot shit becomes a liberatory practice. The chorus provides examples of how Megan performs hot girlhood. She notes that she spends her suitors’ money, avoids “thirsty” behaviors, and centers her pleasure. Her repetition of “I do hot shit” creates a verb collocation that reminds hot girls that liberation requires action.

Megan also represents her liberation by rejecting monogamy. In the first verse of “Hot Girl Summer,” Megan raps, “Handle me? (Huh) Who gon’ handle me? (Who?) / Thinkin’ he’s a player, he’s a member on the team / He put in all that work, he wanna be the MVP (Boy, bye) / I told him ain’t no taming me, I love my niggas equally” (Megan Thee Stallion). Establishing her autonomy with a rhetorical question, Megan demonstrates that no one can force her to settle down. Through her play on the word player, she rejects the idea that men deserve to control relationships and are the only ones who can engage simultaneous partners—aligning with fan interpretations of hot girl summer as role reversal. Through shifting power dynamics in her relationships, Megan defies acceptable performances of Black womanhood and continues to articulate agency as a principle of hot girlhood.

Much of Megan’s music focuses on financial freedom. In “‘Yeah, I’m in My Bag, but I’m in His Too’: How Scamming Aesthetics Utilized by Black Women Rappers Undermine Existing Institutions of Gender,” Diana Khong asserts that, like the City Girls [discussed in William Mosley’s article in this issue], Megan disrupts normative constructions of womanhood by employing a scamming aesthetic. Though Megan does not scam, she implements “financial optimization” (90). The theme of financial optimization destabilizes gender constructions and disregards expectations of women to perform emotional and sexual labor at the will of men. Megan instructs hot girls to know their worth, financially and otherwise. Her refrain in “Hot Girl,” “If he ain’t talkin’ ‘bout no money, tell him ‘Bye, bye, bye,’” the question of “where yo’ wallet?” and the declaration of “I want some money” demonstrate financial optimization (Megan Thee Stallion). She expects compensation for her time and energy. She revisits financial optimization in “Girls in the Hood” as she "spend[s] his income on [her] outfit” (Megan Thee Stallion) but also articulates financial independence with her announcement of being employed at the age of sixteen. The chorus of “Hot Girl” centers financial independence through earning money or “get[tting] a bag” (Megan Thee Stallion). This language filtered out into the hot girl diaspora where fans framed “securing the bag” as real hot girl shit. The tracks add to the principle of freedom that resurfaces in digital counterpublics by showing myriad ways freedom is achieved financially, personally, and sexually.

Seeking Pleasure/Joy & Being Confident

Because her definition of hot girl includes having fun and being the life of the party, pleasure-seeking is paramount to hot girlhood. “Hot Girl Summer” intertwines leisure and sexual pleasure to create a Black feminist pleasure politic displaying “sexual and non-sexual engagements with deeply internal sites of power and pleasure” (Morgan 40). When Ty Dolla Sign raps, “it’s a hot girl summer, so you know she got it lit,” he evokes Megan’s notions of hot girls being the life of the party and hyping up their friends. This song about enjoying summer also indicts gender politics that undermine women’s pleasure. In the third verse, Megan expands the possibilities of hot girl shit, presenting pleasure through partying, drinking, and heterosexual and queer relationships:

Real hot girl shit, ayy, I got one or two baes (whoa, whoa) / If you seen it last night, don’t say shit the next day (hey, hey, yeah) / Let me drive the boat, ayy (yeah), kiss me in a Rolls, ayy (yeah, yeah) / It go down on that brown, now we goin’ both ways, ah. (“Hot Girl Summer”)

She uses her signature phrase to defy heteronormative sites of power but feeds into a sexual binary by “goin’ both ways.” Megan uses “drive the boat,” a term she popularized, which means pouring a shot of alcohol directly from the bottle into someone’s mouth. This action, emblematic of hot girl summer, creates an aesthetic of joy and pleasure for fans who seek to engage in these activities.

“Hot Girl,” a generative work in outlining hot girlhood, centers sexual pleasure and confidence while presenting ideas beyond Megan’s written definition of hot girl. In the song, Megan assumes her Tina Snow persona, described as “player of the year” on the cover of the eponymous EP. Megan notes that Tina Snow is her “pimp persona;” therefore, the music reflects that persona’s confidence and player attitude (Strahan, Sara, and Keke). She exudes confidence by rapping “this pussy really a present” (Megan Thee Stallion). She articulates her sexual power, reminding suitors that it is a privilege to have sex with her. As noted by the lyrics, “I’mma need that head, give me neck like a vertebrae” (Megan Thee Stallion), Megan is not timid about expressing her desires. Her rhetoric aids women in articulating their desires. The arc and art of pleasure-speaking and pleasure-seeking continue in “Girls in the Hood.” She rejects the idea that women should delay or fake pleasure for men by proclaiming, “You’ll never catch me callin’ these niggas daddy / I ain’t lyin’ ‘bout my nut just to make a nigga happy” (Megan Thee Stallion). She centers Black women’s pleasure, which is often considered taboo, through rapping about the necessity of women’s orgasms and her refusal to boost a man’s ego. Many Twitter users quoted this line, with one even calling it a “word” and a “mantra” (@sxyblkchoklat). Listeners use Megan’s bars to critique sexual pleasure dynamics that peripheralize their desires. Using this language, they reclaim their sexual pleasure and contribute to the notion of hot girl rhetoric as a tool for recovery work.

“The Category is Body”: Twerking as Hot Girl Rhetoric

Megan positions hot girlhood as an aesthetic where the body is rhetoric. Speaking through her body, Megan merges the principles of hot girlhood and facilitates a body-positive movement with her confidence in her appearance. Her knees and twerking, topics of conversation across communities and genders, speak of joy, freedom, and confidence, telling stories of Black women resisting respectability. Though twerking is not always sexual, it is commonly sexualized because of the male gaze. Her October 2020 op-ed “Megan Thee Stallion: Why I Speak Up for Black Women,” published in The New York Times, acknowledges how this gaze impacts readings of her body (and lyrics): “When women choose to capitalize on our sexuality, to reclaim our own power, like I have, we are vilified and disrespected” (Megan Thee Stallion). Though twerking is her body’s language of freedom, people who endorse respectability politics weaponize this rhetoric to oppress her. They use her twerking as an excuse to deploy misogynoir and criticize hot girl shit as “thot behavior.” Based on her tweets and lyrics, the goal is not only personal pleasure but also disrupting these cultural conversations that demonize and invisibilize bodies of Black girls and women (Halliday 8-9). The discourses created by Megan’s body illuminate that hot girl rhetoric also exists in the body’s language—not just twerking—but how women’s bodies, especially Black women’s, become sites/sights of (counter) public rhetoric.

Earning internet coinages for adjectival phrases (“Megan the Stallion knees” and “vibranium knees”) and for a song (“Knees like Megan”), Megan’s knees are as influential as her music. With twerking as emblematic of her aesthetic, hot girl rhetoric and Megan’s knees can be discussed alongside Aria Halliday’s arguments about Black girl epistemology in the body. Halliday explores the ways Black girls “create an epistemology of the body through the pleasure of twerking” (2). Megan illuminates how twerking brings collective joy. Her ways of being and knowing align with Halliday’s assertion of “dance as a practice in dialogue, care, and accountability with others who communicate, affirm, and respect Black girlhood” (Halliday 7). Megan understands the power of twerking to bring joy to networks of hot girls who defy respectability politics and confront the subject-object discourse by twerking for pleasure and entertainment. The Black girl epistemology is present in “Hot Girl.” She opens the song with “all the hot girls make it pop, pop, pop,” declaring that the collective twerks. In conjunction with her lyrics, Megan’s celebration of twerking illuminates hot girl rhetoric as a language for homegirls and communication of community and agency. As Halliday positions twerking as a disruption of cultural conversations, it becomes a mode of talking back and talking shit. Though Megan dedicates minimal space to discussing twerking in the analyzed songs, she makes it the signature dance accompanying her signature phrases. Through twerking, Megan presents the principles of hot girlhood, but for audiences to understand twerking as an agentic act, they must “listen” to her body, not just gaze at it.

Conclusion

Megan’s hot girl rhetoric aligns with a carefree Black girlhood that embodies Black women scholars’ notions of ratchet, “talking back," and bringing the wreck. Hot girl rhetoric’s popularity is a product of its cultural relevance, versatility, and relatability. Hot girl became a meme, a vibe, and an interpretive community for Megan’s fandom of hot girls and hotties. Her language carves space for collective rejection of patriarchal norms and celebration of the complexities of Black womanhood. Through her vocabulary, Megan aligns with Diana Khong’s assertion that “Existent systems of power and privilege are being reimagined, not only in the present…but in enduring ways as they impart rhetorics of empowerment and autonomy to their predominantly female fanbases” (98). Her look and lyrics exude confidence and show hot girlhood as refusal, independence, empowerment, community, pleasure, and ratchetness. Her concept of hot girlhood provides a liberatory praxis that encourages people, especially Black women, to talk their shit.

Works Cited

@AnnieNickens. “Niggas just ASSUMED hot girl summer was a hoe summer. Just like niggas.. always jumping to conclusions. Hot girl summer is just girls knowing our worth and doing what we want. But y’all don’t wanna hear that tho.” Twitter, 3 July 2019. 11:13 pm, https://mobile.twitter.com/AnnieNickens/status/1146633097418555397.

Bailey, Moya. Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance. NYU P, 2021.

Cooper, Brittney C. et al. The Crunk Feminist Collection. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2016.

Duthely, Regina, “Black Feminist Hip-Hop Rhetorics and the Digital Public Sphere.” Changing English, vol. 24, no. 2, 2017, pp. 202-212, DOI: 10.1080/1358684X.2017.1310458

Eazy-E. “Boyz-n-the-Hood.” Ruthless. 1987.

Genius. “Megan Thee Stallion ‘B.I.T.C.H.’” Official Lyrics & Meaning Verified. 26 Mar. 2020 YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CV40Rk4qwuA.

Halliday, Aria S. “Twerk Sumn!: theorizing Black girl epistemology in the body.” Cultural Studies, 2020. pp.1-18, https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1714688.

hooks, bell. Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. South End P, 1989.

@iammarleydias. “Hot girls stand up for what’s right. Respect the humanity of ALL Black girls.” Twitter, 15, Mar. 2021. 12:32 pm, https://twitter.com/iammarleydias/status/1371877155458650112.

Jennings, Rebecca. “7 Questions about hot girl summer you were too embarrassed to ask.” 9 Aug. 2019, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/7/12/20690515/hot-girl-summer-meme-define-explained.

Khong, Diana. “Yeah, I’m in My Bag, but I’m in His Too”: How Scamming Aesthetics Utilized by Black Women Rappers Undermine Existing Institutions of Gender.” The Journal of Hip Hop Studies, vol 7, no.1, 2020, pp. 87-102.

Love, Bettina L. “A Ratchet Lens: Black Queer Youth, Agency, Hip Hop, and the Black Ratchet Imagination.” Educational Researcher, vol. 46, 2017, pp. 539-547.

Megan Thee Stallion. “Girls in the Hood.” Good News. 1501 Certified. 2020. Spotify.

----. “Hot Girl.” Tina Snow. 1501 Certified. 2018. Spotify.

----. “Hot Girl Summer.” 300 Entertainment. 2019. Spotify.

---. “Megan Thee Stallion: Why I Speak Up for Black Women. The New York Times. 13 Oct. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/opinion/megan-Thee-stallion-black-women.html.

---. “Savage.” Suga. 1501 Certified. 2020. Spotify.

“Megan Thee Stallion On Her Alter Egos Tina Snow, Hot Girl Meg And Suga.” YouTube, uploaded by Strahan, Sara, and Keke. 11 Mar. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d6ksafHP0NY.

Meggs, Michelle. “Is There Room for Ratchet in the Beloved Community?: If You’re Not Liberating Everyone, Are You Really Talking About Freedom?” Womanist Ethical Rhetoric: A Call for Liberation and Social Justice in Turbulent Times, edited by Annette Madlock and Cerise L. Glenn, Lexington, 2021, pp. 63- 76.

Morgan, Joan. “Why We Get Off: Moving Towards a Black Feminist Politics of Pleasure.” The Black Scholar, vol. 45, no. 4, 2015, pp. 36–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24803042.

Mouse on Tha Track. “Knees Like Megan.” 300 Entertainment. 2021.

Pearce, Sheldon. “Megan Thee Stallion: Girls in the Hood.” Pitchfork, 26 June 2020, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/tracks/megan-Thee-stallion-girls-in-the-hood/.

Pickens, Therí A. “Shoving Aside the Politics of Respectability: Black Women, Reality T.V., and the Ratchet Performance.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 41–58.

Stallings, L. H. “Hip Hop and the Black Ratchet Imagination.” Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Gender, and the Black International, vol. 2, no. 2, 2013, pp. 135–39.

@sxyblkchoklat. “‘You’ll never catch me calling these niggas daddy, I ain’t lying about my nut just a make a nigga happy! Lifestyle when a nigga can’t fit a Magnum. It never happened if the dick wasn’t snappin’” Come on Meg! If it that wasn’t a word. When I tell you that’s my Mantra I live by!!” Twitter, 25 June 2020. 11:55 pm, https://twitter.com/sxyblkchoklat/status/1276378628109074434.

@theestallion. “Real hot girl shit= being free and unapologetically you, showing off your confidence, hyping up your friends, not taking shit from NOBODY etc.” Twitter, 25 Nov. 2018. 11:30 pm, https://twitter.com/Theestallion/status/1066927257749467136.

---. “Being a Hot Girl is about being unapologetically YOU, having fun, being confident, living YOUR truth, being the life of the party etc.” Twitter, 17 July 2019. 11:27 am, https://twitter.com/Theestallion/status/1151528790906081281.

Thompson-Jones, Amoni. “The Politics of Black Girlhood and a Ratchet Imaginary.” The Black Girlhood Studies Collection, edited by Aria Halliday. Canadian Scholars, 2019, pp. 81-101.