The Transect as a Method for Mapping and Narrating Water Landscapes: Humboldt’s Open Works and Transareal Travelling

by Lisa Diedrich, Gini Lee, and Ellen Braae

published November 2014

1. Capturing Site Qualities: Relational Atmospherics:

In current urban design and landscape architecture practice, designers often address sites from static and material perspectives: as empty grounds where new design inventions are played out at the whim of their creators. Despite such design works claiming site specificity as their guide, generic outcomes that ignore or overlook local conditions abound, lacking response to ephemeral yet essential site properties such as temporal dynamics and atmospheric encounters. The focus of this NANO note seeks methods for site exploration to inform site transformation through representing the narrative, ephemeral, and dynamic qualities of places that could contribute to open work design approaches.

Fieldwork operations allow the identification of water landscapes as potent areas for investigation of transient sites (Parodi), drawing upon the understanding that the influence of water conditions on human settlements and the effects of human practices on aquatic systems over time can best be apprehended by investigating conditions of economic and social change through the lens of climate dynamics. Normative solutions often appear inappropriate to specific water landscapes as situations exposed to on-going change are affected by both nature and culture forces. We therefore propose an altered acknowledgment and representation of site particularities to apply to design for water landscapes. Seeking a shift from the imposition of universal design-based solutions into a more nuanced transformation of sites, we apply a narrative open work design method that can be variously described as deep mapping and/or transareal travelling. This context motivates us to formulate methods that enable designers to better capture the more intangible aspects of existing sites to support relational transformation. Our particular aim is to improve designer understanding of water landscapes, especially the ephemeral and constitutive features of such water landscapes. We trust that such an understanding will lay the foundation for improved landscape design and development through positing critical methods based upon site experience.

These methods employ the transareal and trans-scalar understanding of Alexander von Humboldt’s scientific model, framed through the landscape architecture lens in a problem-oriented research approach that seeks to map and narrate the relational, the dynamic, and the atmospheric qualities of sites. Additionally, the transareal transect method enables designers to focus and reflect on site qualities as a mobile form of on-site exploration, complementary to the in-studio study of documented site conditions such as statistics, cadaster and topographic maps, Google searches, and other pragmatic diagramming techniques. This fieldwork method seeks to reveal interactions with the site in identifying the dynamic and changing qualities of places and their environmental contexts, where the site contributes as a maker of experience rather than simply as a bearer of recorded meaning (Kahn 180).

We three researchers from Munich, Melbourne, and Copenhagen respectively, also seek ways to plan future site investigations, while in our dispersed states, through employing technologies such as digital and virtual communication systems. Before travelling, we use historic and contemporary maps to define the intended transect itineraries and to propose routes in the abstract, sometimes guided by previous knowledge or clues from other collaborators. The transect line is then drawn across territories free of judgment as to ease of access across land, topography, or sea. The reality of accessibility confronts us when we land; the organizing transect line must necessarily deviate from the imposed path—the topography, site conditions, time, and serendipity remake the linear journey into a potentially deviant excursion. The scientific ordering implied by the transect line becomes the designerly open work of twists and turns, circling, double-backs, and altered agendas. During our deviations, we map the factual itinerary and what we find along it, locating sites according to their qualities as water places. After travelling, we elaborate our findings through ongoing mapping, collaborating at distance, communicating through drawing, annotating, and sharing imagery and text—writing and over-writing our experiences onto the cartographic diary—an open work in itself. Essentially, we focus on the iterative activity of mapping—enabling us to continuously reveal site qualities as narratives exposed by the site to ultimately effect potential design for the site.

2. Positioning Fieldwork:

Our approach goes beyond cartography theories that are generated by collecting and collating secondary data and imagery, which is then used to create a visual map of territories without the necessity for landing on site—in effect an over-sight perspective. James Corner and Alex S. MacLean’s compelling visual mapping of the American condition or Laurel McSherry’s Commonwealth mappings are two cases in point. While our visual response infers the influence of methods and themes of others through the juxtaposition and overlapping of cadaster maps, photos and drawings, annotation of experiences, and an expression of the hydrology and politics of site, our position is more within the realm of immersive and immediate site exploration. We abandon the distant point of view. The alternative design approaches of Anaradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha on the one hand—aestheticizing on-site experiences into complex and artful over-site and out-of-site mappings—and those of Alexandre Chemetoff on the other with his refusal to transfer on-site experiences into another medium beyond site transcriptions, compare well to our on-site approach. We situate our work between the on-site and the over-site in reference to early land artist Robert Smithson, who aimed at transferring impressions and thoughts from site to elsewhere, producing his non-sites. He was not, however, producing cartographies. To appropriate James Corner, our eidetic operations rather seek a narrative cartography to enable translation from site to non-site—from here to there. This narrative cartography escapes both the raw status of transcriptions and the artful codification of mappings; it enables a tool for designers to mediate insight and impressions from one site (in order to express site qualities and potential transformations) to another located far away.

3. Transareal Travelling and the Open Work:

Our inspiration for this approach is drawn from another journey through the writings, mappings, and itineraries of the 18th and early 19th century traveller, writer, and explorer Alexander von Humboldt—our methodological (and spiritual) guide. Appropriating his transareal approach, understood as exploring a particular geographical and cultural area from the perspective of experience of another place, allows for generating new knowledge through relational thinking and an open-minded redefinition of local empirical studies. Humboldt regarded science as a mobile, transareal enterprise that moves across disciplinary and geographical boundaries and territories (Ette; Kutzinski). As witnessed in his journals and through recent scholarly reinterpretations, he practiced mobility of thought and application in his fieldwork through mapping and writing.

Humboldt’s applied approach assists us to re-envisage the epistemology of current scientific approaches to landscape investigation. His work operated within an environment characterized by intense global movement through seafaring and increased trade. Now similar, yet arguably more virtual, conditions of movement are driven by the current globalized economy. According to Ottmar Ette’s Alexander von Humboldt und die Globalisierung. Das Mobile des Wissens, in response to a changing worldview, Humboldt advanced two “epistemological revolutions” (76-83). At the time these approaches were not fully exploited and subsequently they were forgotten or misinterpreted as scientific research was segmented into specialized areas in the late 19th and 20th centuries. For 21st century designers/researchers, the original Humboldtian approaches appear to deliver the basis for examining an appropriate multi-scalar site exploration method.

Humboldt’s first epistemological revolution consisted in the rejection of pure reflection at distance (epitomised by the encyclopaedic knowledge of the French philosophers of 18th century such as Denis Diderot, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Montesquieu) and posited empirical exploration on site as the new authority for reliable knowledge generation. Humboldt’s two great travels to the Americas via the Canary Islands (1799-1804) and to Central Asia (1829) adeptly depict his mode of practice through his reliance on fieldwork and immediate observation. Upon returning home, he eventually related his findings through critical thought leading to writing and publishing visual impressions, sections and maps in an ever-evolving process of knowledge generation. His post-American travel report Relation historique, published between 1814 and 1825 in Paris, and in his seminal work Kosmos, published between 1845 and 1862 in Stuttgart and Tübingen are examples of such publications. This led to his second epistemological revolution. In his writings since the Relation historique, Humboldt posited knowledge as an open work, expanding his research to cross boundaries between areas of study, exploring their interrelatedness and relational dynamics, and regarding science as a transareal pursuit.

Humboldt’s appreciation of open-ended and relational methods helped to generate his particular format of writing, communicating, and publishing. His texts, such as the Relation historique and Kosmos, feature multiple cross-references and side stories in a meandering footnote apparatus. The Relation historique, for example, was conceived as a book series with forthcoming editions and included comprehensive publication of images produced by artists utilizing his sketches and notes. This particularity has also earned him disdain, and many of his thousands of pages have been published in falsifying shortcuts and misinterpreting translations. Today, researchers such as Vera Kutzinski, Ottmar Ette, Laura Dassow Walls and others, united in the Potsdam International Network for TransArea Studies (POINTS), contend that Humboldt’s time has come again and as a scientific figure, his work embodies such merit as to be rediscovered and reinterpreted from primary sources.

Humboldt’s claim seems to be both relevant and contemporaneous to our design research perspective. In an interrelated world, mobile scientific inquiry and method can help generate appropriate knowledge for the design of complex contemporary landscapes. Our travelling transect aims at translating an historical approach into contemporary scientific/design method: Humboldt’s site thinking is on-site thinking and his site knowledge is open-ended evolutionary knowledge.

4. Conceiving and Testing a Contemporary Fieldwork Method:

In April 2013, the Canarysect was conceived as a first travel experiment and transareal method performed on the Canary Islands archipelago. We selected these particular water landscapes to explore imagined transareal travel employing transect as an organizing process. Tracing Humboldt’s journeys we saw these islands presenting a compelling on-site laboratory as they are commonly acknowledged as a summer destination, providing a range of coastal, urban and topographic features supported by balmy weather conditions in accordance with the qualities evident in international and generic tourism locations worldwide. We sensed that as the Canaries host a maximal variety of topographical and water conditions over a compact geographical expanse, we would be able to explore their specificities in the context of our transect experiment. Furthermore, following Ottmar Ette’s understanding of the Canaries as “comprising the whole world in an island” and a specific “island world” at the same time (Inselwelt in German; see Gebauer 11-14), we conceived of the Canaries as a microcosm of the globalising world. The Islands’ distinctive landscape qualities, which alter from island to island, infer dynamic and changeable site conditions responsive to local ecologies and economies. Our intent was to seek out the particular atmospheres and materialities that lie beneath or adjacent recent development in association with water landscapes and forms.

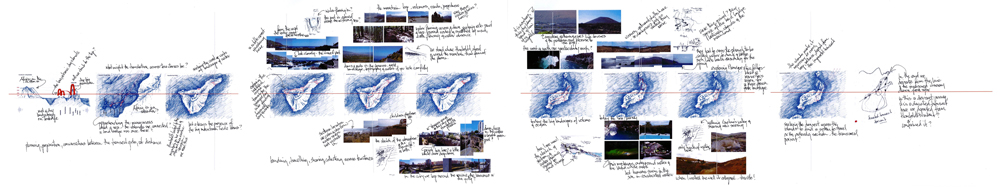

Before the trip, we traced an itinerary, selecting three islands of the archipelago, Tenerife, Lanzarote, and La Graciosa. The itinerary was highlighted as a red line over a set of hand-drawn maps. We sought to commence at Humboldt’s test site on the island of Tenerife where he ascended the Teide volcano. When Humboldt sailed from Spain to the Canaries in 1799, his team landed first at La Graciosa (17 June 1799), the small satellite island of Lanzarote in the North of the archipelago, erroneously thinking it was Tenerife—his first deviation. As Alfred Gebauer notes in Alexander von Humboldt. Seine Woche auf Teneriffa 1799,they then continued to Tenerife to study the island over only a week (19-25 June 1799), especially the Northern slope and the crater of the Teide Volcano.

On site, we had a week to travel along the line prescribed by our itinerary, always receptive for deviation, and we took with us a set of tools to guide our capture of site particularities: Photographing and filming to enable capturing atmospheres through framing unique moments and for contemplating details, colours, structures, scales, and sounds to illustrate sequences of site dynamics. Sketching and hand-drawing to permit flexible depiction of details in a semi-automatic reflection mode, allowing superimposition of various observations of forms, structures, objects, and their associations, brought to clarity through annotation in field notes. Along the way, conversations with locals, designers, and professionals involved in landscape development helped us to gather information and insight into current discourses and practices about the dynamics and relationships of local conditions. These collaborations and associations promoted a community of practice around the site. Now, after the fieldwork, our findings consist of a collection of raw material: photos and small films, sketches and annotations, collections and interview notes. In accordance with the open work method, this material is now sorted, evaluated, combined, interpreted, synthesized, and elaborated into exhibition, writing and the expanded cartographic diary that seeks to challenge conventional cartography.

5. Mapping and Narrating from Site:

Our days of transect travelling across Tenerife, Lanzarote, and La Graciosa provided us with more than enough material—from wet to dry, from volcano to coast, across impassable rock plains to black sand beaches, and from sub-tropical density to bare aridity. It also tuned our expectations for crossing territory, forcing us to slow down when necessary, even though we had limited time for our excursions. This temporal aspect of travelling landscape with intent is impossible to convey on conventional maps far from site—this is the benefit and challenge of fieldwork.

Design research methods that arise from transect travel empower the intangible qualities of landscape elements to operate as prompts for recording and conversation towards collective mapping and narrating. Our field notes and photos reveal atmospheres of exposure and enclosure, danger and protection, the wet and fresh, the salty, the dark and the bright, and the dynamics of erosion over time. Our films reveal water dynamics over short sequences, yet they convey passing and repeating patterns day by day. Our sketches reveal relationships of landscape entities such as coast, ravines, cliffs, and slopes at a scale beyond detail. Together, these prompts relate to natural systems such as: geology, topography, wind and the water regime of the Canaries, the islands as part of the African tectonic plateau that drifts eastwards creating volcanic activity, the volcanoes that ejected the lava that ran down the slopes forming the rocky coasts, the trade winds coming in and the northern coasts exposed to them. The social and economic results of Canarian environmental dynamics show extreme cultivation of the natural formations and resources into places of great aesthetic beauty; the natural bathing pools fashioned into the rocky coastlines, evolutionary volcanic agriculture, the closeness of the Sahara and the appearance of an African architecture and urban influence, deposited yellow sand that now come to surface through wind erosion creating the bright land masses of La Graciosa and the most-favored tourist beaches, and finally the shallow waters between the eastern Canaries and the coasts of the African shelf to create the rich Canarian/Saharan fishing bank and the shellfish rocks of La Graciosa.

Application of the various tools utilized while transecting the relational, the dynamic, and the atmospheric qualities of water landscapes confirmed many of our research and methodological expectations and tested others. We had to distinguish between firstly the relational being spatial, i.e. the relations between objects, and secondly the trans-scalar, i.e. the relation between overall structures, functions and forces, site and program. Sketches could partly represent trans-scalar relationships. Dynamic change over time—cycles and flows—is traced on site, through the camera and the sketch. Atmospheres as spatial, haptic, and temporal conditions typically were the most difficult to record through experiments with photography, both sequential freeze frame and video capture. However, we find that much knowledge is produced in between the tools or in their intersection, through collaborative conversation, modelling, annotation, and over-writing.

6. Annotation, Cartography, and the Diary:

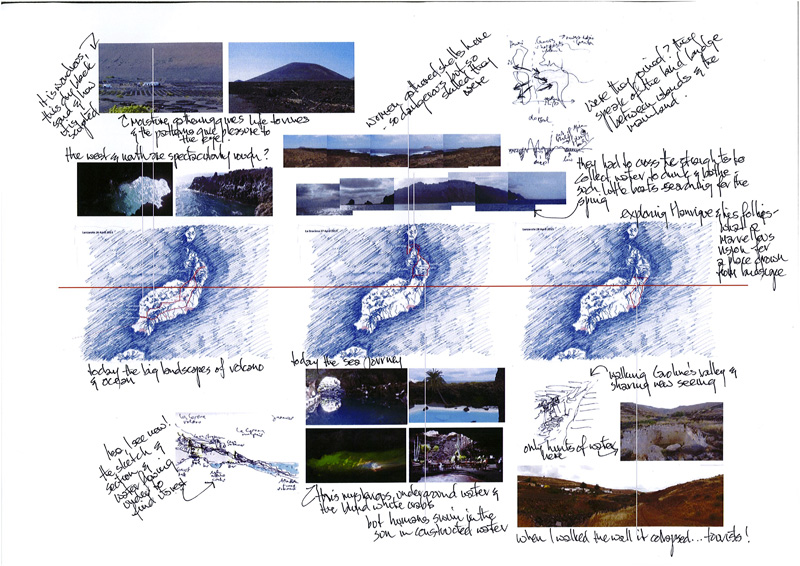

This annotated, cartographic diary is the first production after the Canarysect. It combines pre-travel, travel, and post-travel material and marks the red line indicating the linearity and dynamics of our imagined travel, day after day, island after island. Along this line, daily itineraries are displayed through pre-prepared map sketches, the overall section and maps of the archipelago. This base drawing terminates with the epistemic diagram which brings the travel along a spatially deviant transect into graphic realization. Above and below the map sequence, photos and sketches from site communicate some of the prompts, i.e. places of situated knowledge, which captured and sometimes deviated the researchers’ attention on site from the planned itinerary. Various local and global issues crystallize in these areas, especially as they are related to the tensions among everyday Canarian life and economies and international tourism and extractive industries development alongside world heritage landscapes. Such areas include: the rocky coasts of Garachico, El Médano on Tenerife, Janubio on Lanzarote, the western shores of La Graciosa, the cultivated ravines of the Orotava valley, the Barranco de Santos in Tenerife, and the Los Valles and the Jameos de Agua on Lanzarote. At the same time, the photos and maps also depict atmospheric site qualities. Composed at first by Diedrich and drawing upon work prepared for exhibition, this cartographic diary was subsequently annotated by Lee to reflect upon the thoughts, experiences, moments of clarification, and ongoing conversations across collaborators. These slight narrative exchanges are both prompts and confirmations of moments recalled through the medium of image, panorama, and sectional sketch. Temporal moments encountered while travelling could be chronicled through image and text, and the short film and sound bites taken at unique moments during the visits to places were able to capture the atmospheres of water movement visible in the natural and designed sculptural forms so characteristic of these islands.

A spatial review in real time, this annotated cartographic diary opens up to the next iteration, annotation, and/or journey. It expresses an open-ended method of communicating site after the first event to make subsequent events in abstract time. This kind of mapping is both a spatial and a temporal chronology. The use of videos and sound manipulation allows for the repeatable expression of atmospheres recorded in the field and of the moment. This cartography is a trans-scalar representation of a sequence of island experiences—it is both an account of a fieldwork itinerary, and at the same time an open work that provokes further mind journeys after the initial landing on site and with the included contributions offered by the various fieldworkers to the diary.

7. The Deviant Transect:

We set out with the idea of the travelling transect assuming that pre-knowledge enabled us to define the itinerary, and that we would probably allow serendipity to change our itinerary on site if our attention was captured by something that provoked deviation. On our Canarysect trip, it became clear that the deviation was what generated new knowledge, on-site, and also post-travel through ongoing mapping and narrating. Future transects drawn from this knowledge would again encourage deviation, confirming our method as open-ended, producing evolutionary, never-complete knowledge.

As in Humboldt’s tropic(al) constructions, the shift between the planned itinerary and the factual on-site experience enables discovery. The shift, or the trope, in Ette’s words, is border crossing, leaping forward towards a deviant itinerary. The shift depends on the researchers’ knowledge and interests, their moves, motion and emotions, mediated by their apprehension of site and the particular temporal and physical conditions encountered while travelling. It depends on the particular itinerary and who travels—as the knowledge generated each time is mediated through negotiations around the inherent nature of mapped and collected materials. Co-opting Humboldt’s transareal fieldwork approach facilitates landscape research that imbues mapping and reproducing methods with ephemeral and atmospheric site qualities. Through the medium of archipelagic travelling, we appropriate these evocative techniques and propose a form of landscape research that constitutes a journey from on-site to non-site, from physical to mental site, from thought to conversation, as we move back and forth. This is an inclusive journey that invites engagement with landscape design as a moment within ongoing and open works.

Works Cited

Chemetoff, Alexandre. Visits. Town and Territory—Architecture in Dialogue. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2009. Print.

Corner, James, Ed. Recovering Landscape Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural P, 2009. Print.

Corner, James and MacLean, Alex. S. Taking Measure Across the American Landscape. New Haven: Yale UP, 1996. Print.

Ette Ottmar. Alexander von Humboldt and Hemispheric Constructions. In: Kutzinski V. et al. Alexander von Humboldt and the Americas. Berlin: Walter Frey. 2012. 209-236. Print.

Ette, Ottmar. Alexander von Humboldt und die Globalisierung. Das Mobile des Wissens. Insel: Frankfurt a.M., 2009. Print.

Gebauer, Alfred. Alexander von Humboldt. Seine Woche auf Teneriffa 1799. Verlag Verena Zech: Santa Úrsula, 2009. Print.

Humboldt Alexander. von Ansicht der Kordilleren und Monumente der eingeborenen Völker Amerikas. (1810-13) Eichborn: Frankfurt A.M., 2004. 10-13. Print.

Humboldt Alexander. Von. Kosmos. Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung. (1847) Eichborn: Frankfurt A.M., 2004. Print.

Kahn Andrea. “Overlooking: A look at how we look at site or… site as “discrete object” of desire.” Desiring Practices. Architecture, Gender and the Interdisciplinary. Eds. Sarah McCorquodale, Katerina Ruedi, Sarah Wigglesworth. London: Black Dog Publishing, 1996. 174-185. Print.

Kutzinski, Vera., Ette, Ottmar., Walls, Laura Dassow. Eds. Alexander von Humboldt and the Americas. Berlin: Walter Frey, 2012. Print.

Mathur, Anaradha. “SOAK Mumbai in an Estuary.” New Delhi: Rupa & Co: 2009.

Parodi, Oliver. Towards resilient water landscapes. Design research approaches from Europe and Australia. KIT Scientific Publishing: Karlsruhe, 2010. Print.

Smithson, Robert. “A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites” Unpublished Writings in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, 2nd Edition. Ed. Jack Flam. Berkeley: U of California P, 1996. Print.