An Interview with Melissa A. Weber, Curator, Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, Tulane University Special Collections by Erin Kappeler and Ryan Tracy

#

An Interview with Melissa A. Weber, Curator, Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, Tulane University Special Collections

by Erin Kappeler and Ryan Tracy

Published June 2022

Abstract: This interview with musicologist and curator Melissa A. Weber explores the connections and disjunctions between institutional archives and surrounding communities and the unique challenges and joys of archiving musical cultures and histories.

Keywords: music, jazz, gender, archives, Tulane, New Orleans

Introduction: In 2019, Melissa A. Weber was named curator of the Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz at Tulane University Special Collections, a renowned repository of music history. Weber has an encyclopedic knowledge of New Orleans music—which, as she explains, forms the core of all contemporary American music. We took this opportunity to speak with Weber about the connections and disjunctions between institutional archives and surrounding communities and the unique challenges and joys of archiving musical cultures and histories.

• • •

Erin Kappeler (EK): It was recently announced that the Hogan Jazz Archive has a new name and a new mission. It is now the Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, and has an expanded scope to include late-20th-century and 21st-century music. How do you think this change is going to affect how researchers and community members think about music in New Orleans? Do you think the expanded scope will allow for more thinking about how gender and genre shape each other?

Melissa Weber (MW): The renaming and rebranding is certainly expansive, and I counter that the new title is actually more accurate and responsible than being entirely new. The name now reflects and publicly acknowledges so many collections that currently are part of the Hogan Archive, while proactively representing anticipated collections, as well as interest in those collections. Simply put, our collections already tell stories of New Orleans-based music culture and music making around rhythm and blues, early rock & roll, brass bands, gospel, even the music of Mardi Gras Indians (also recently referred to by many as Black Masking Indians). While everything derives from blues and jazz, it is my preference not to slot everyone under a moniker of “jazz,” because that would be inaccurate. Even when it comes to New Orleans jazz, our current collections heavily feature materials representing traditional jazz of the early-20th century and mid-20th century. When it comes to materials and stories of the late-20th century, moving from 1970 forward, there are many gaps—especially when it comes to contemporary jazz, funk, hip hop, or other genres and cultures. The expanded scope ensures that we have an accountable collection development policy that represents the depth and breadth of our music and our community.

If this change in our name and public-facing policy results in anything, it’s going to open up the possibilities for who feels welcome to interface with the collections, and for who can now find empowerment in seeing themselves in the collections. It is my personal hope that it goes even farther than that, and starts conversations among individuals and families who may have never utilized or encountered an archives repository in their lives, making them aware of what archives are and why they should archive their own stories and lives. Black people in New Orleans remain the majority, according to census numbers, and continue to shape culture. But most of our collections currently and disproportionately are of and from white people. This tells me that the word has not gotten out about the power of archives to Black people and other people of color. Our stories and our perspective in those stories is important, and it’s important to start with the conversation of what archives are, and then we can move to why and how someone would benefit from utilizing them.

And as far as thinking about music in New Orleans, it’s imperative to understand that New Orleans is not a periphery music scene. The foundation of popular music in the United States comes from New Orleans music characteristics and innovations, whether it’s the concept of call and response and crowd participation, to vocalizations of bending notes and popularizing scatting, to an emphasis on polyphonic rhythms—everything emerges from this place. So the new, full Hogan Archive title expresses this. It gives form to who we are, and also nods to the fact that more work needs to be done and will be done to share the complete stories of the totality of New Orleans music.

Gender is also a necessary part of this conversation, and is a reminder not only to researchers but also to archival professionals that our stories need to actively reflect gender diversity and equity in order to tell them fully.

Ryan Tracy (RT): The Hogan Archive’s desire to encourage research among people not institutionally recognized as scholars seems to be an important goal in terms of redefining the archive itself as an institution of, by, and for the community it resides in. I’m also intrigued by the idea that an archive that serves community needs may prompt people to enact archival processes of their own. Can you say more about the role an archive can play in community and individual self-empowerment? Why haven’t more New Orleanians looked to institutional archives as locations in which their stories can be told and preserved? And what kind of shape might an archive take in the future if more people utilize an archives repository to leave an “official” record of their contribution to musical culture?

MW: The mission of Tulane University Special Collections (TUSC) is indeed to encourage and expand the possibilities of research, and that includes aligning ourselves with our local and regional community in addition to that of our institution. I’d also like to add that the Hogan Archive is a unit of Tulane University Special Collections (TUSC), which also includes the units of the Louisiana Research Collection, University Archives, Rare Books, and the Southeastern Architectural Archives. We are unified in our efforts toward responsible stewardship, facilitating access to materials, and documenting and celebrating our community.

One of the most powerful functions of archives, to me, is to reflect community and who we are. We have to archive our stories in order to have our communities reflected. Everyone is a part of this work, not simply archival professionals or librarians. It is empowering to know that everyone’s story plays an important role in the record of history, if it’s kept. Archiving our own stories is a personal responsibility not only to ourselves, but to future generations.

I can also speak to why more New Orleanians, or anyone in general, who aren’t familiar with institutional archives in particular are less likely to utilize them. Personally, I didn’t know what the purpose of an institutional archive was when I was growing up. I didn’t learn what more traditional archives were until I began doing my own independent research on various projects. And even then, it wasn’t scholarly research, so I felt that my searches would not be welcome in university archives. There is also a trust barrier that has to be addressed because people are simply not going to freely engage with an institution or university unless they feel like they’re a part of it. I’m here to say that everyone is a part of it. Archives are for the community—to me. I’d like to help break down walls around the concept of “archives.” I’d like to share with people that our collections are rich for anyone doing research of any type, not solely academic. But research does not and should not have to be the end goal for many people. Archives are wonderful resources for family and geneaological research, and for my personal favorite activity, lifelong learning. I also would love for more of us to really want to see ourselves in archives, and to know that our stories—on any topic—are important and will continue to be centuries down the line. The more people who contribute to leaving their legacy by archiving their stories, their histories, and their lives ensures that gaps in those stories and histories don’t remain empty. Telling a complete story of our history is dependent on complete community representation and participation in archives. How that works is one of the things I’m most excited about discussing with people every day, not only when I’m at the Archive, but also when I’m not in the office and just on the street talking to strangers and meeting someone new who’s never heard of the Hogan Archive or any special collections repository.

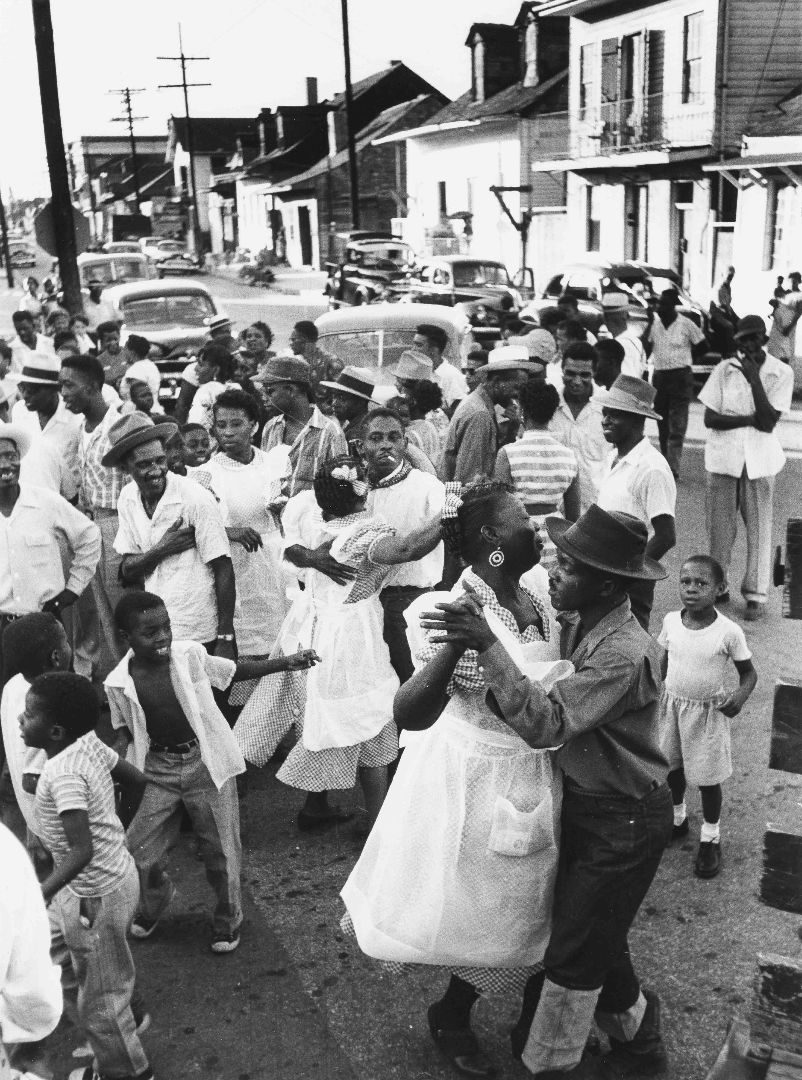

People dancing in the street in the Treme, Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography, Box 8 #24, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA. https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A21955. [high-res scan requested 1/19/2022]

EK: New Orleans music scenes tend to come in and out of the spotlight—I’m thinking of Beyoncé’s “Formation” as a relatively recent example of high-profile attention to specific New Orleans musical cultures. What do you think are some of the lesser-known innovations or currents or trends in New Orleans music scenes now? How have communities that are connected through live music and communal events coping and adapting to our current pandemic reality?

MW: New Orleans is quite unique from other cities, especially related to culture, in that we cherish tradition. This provides a strong continuum of our music culture. Musicians who are native New Orleanians often talk about elder musicians who taught them when they were younger, giving informal lessons or sharing wisdom. That’s not something you hear about as much in some other music communities. So tradition is strong here, but young people are always going to create and innovate. So you do still have a thriving music culture with artists of all ages playing traditional New Orleans jazz, or contemporary jazz, or brass band styles both traditional and contemporary, or funk with a nod to what The Meters were doing in the late-1960s and 1970s, for instance. Newer innovations can be inspired by what’s happening outside of New Orleans, things that we hear in broadcast media or social media or in travels. It shows that we’re not insular or above influence. Trends are always going to skew to what young people are doing, but our New Orleans traditions are the throughline. My favorite recent examples include some of the younger Mardi Gras Indians or Black Masking Indians whose lyrics speak to contemporary issues happening in the community. Flagboy Giz of the Wild Tchoupitoulas tribe released an online video for his song “Gentri Fire in the City,” with powerful lyrics like, “They gentrifying in New Orleans, gentrify and make the locals leave, gentrifyin’ where you call home, gentrify ‘til all the Black people gone.” That’s from his album, which is available digitally, titled Flagboy of the Nation. The 79rs Gang, featuring Big Chiefs Romeo Bougere and Jermaine Bossier, is also doing similar work and incorporating elements of modern hip hop and electronic sounds with traditional New Orleans brass band instruments underneath powerful lyrics. For instance, their 2020 album Expect the Unexpected has songs about Hurricane Katrina and even one called “Culture Vulture,” which calls out photographers and researchers who document Mardi Gras Indian culture but don’t give back to their community.

As far as how New Orleans’ music community is dealing with the pandemic, as things open up, everyone can finally see a light at the end of the tunnel—and that’s both a creative light and a financial light. The nature of so much of New Orleans music culture, both traditional and non-traditional, comes out of gathering and community, though. You can’t get that same energy and feel on an Internet livestream. It will take slow steps. For instance, small gatherings are now allowed during the current phase we’re in [summer 2021], but dancing is not. New Orleans music is dance music. But safety comes first. My hope is that musicians and members of the cultural community are included in every conversation regarding reopening our places and spaces of gathering and music making. Without their input and involvement, we may as well be speaking about another city.

RT: Speaking of genres…“New Orleans music is dance music” merges two modes of cultural expression that are often kept separate in Western epistemologies of the arts. I wonder if you could talk more about the location of dance in the Hogan Archive. Where is it most present or represented? What kinds of archival practices preserve the choreographies of musical culture, whether it be through informal gatherings, spontaneous dance breaks, the flows of life that musical performances organize in public and private spaces, or conventionally staged performances on the street or in theaters?

MW: The most noticeable evidence of dance shows up in photographic form—in our digitized photo collections such as the Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography and the Hogan Archive Photography Collection. There are countless images of dancing throughout the decades whether at second line parades and jazz funerals, concerts, Carnival balls, or other gatherings as wide ranging as picnics and church services. Dance is also represented in several other collections outside of the photography collections. It’s literally everywhere because dance so closely intersects with New Orleans culture and history, going back to accounts of ring shouts and Bamboula dances of Black people during the period of enslavement in America. While dance is most obvious in our photographic collections, it shows up in manuscripts and research files. It’s present in the ephemera and flyers of dance recitals and invitations. It’s naturally represented in the sheet music for various dances, from the Black Bottom to the Cake Walk to various 19th century quadrilles and waltzes. We even have materials related to noteworthy Black choreographer Katherine Dunham's work with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. And dance, like any subject, is archived simply via a person’s decision to document a moment. It is that simple and powerful. Because someone personally archived and then shared their materials, we now have an archival record of this history.

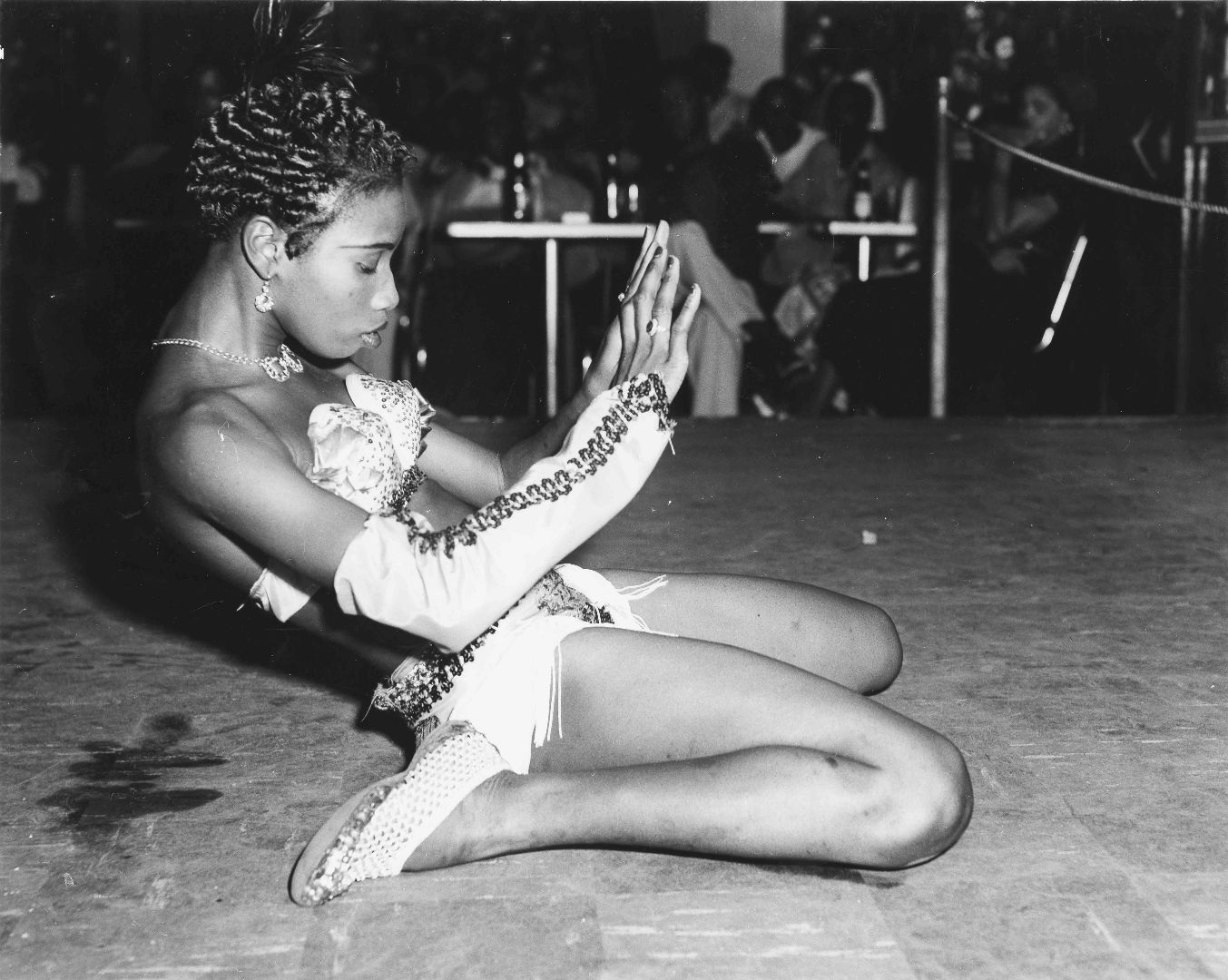

A dancer on stage at the Tijuana Club, Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography, Box 3 #53, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA. https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A21488. [hi-res scan requested 1/19/2022]

EK: Are there any holdings in the Hogan you want to highlight? Clips we might be able to feature on the website?

MW: I love to share information about the Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography because it’s a well-organized digital collection, and anyone can access it from wherever they may be around the world. The collection features over 700 images of New Orleans music, culture, and life, shot between 1947 and 1960 by photographer Ralston Crawford. It’s one of our most requested collections for use.

EK: The Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography is wonderful; thank you so much for highlighting it! Since our issue is focused on gender and genre in pop music, Ryan and I were especially drawn to the images of dancers and drag performers at The Dew Drop Inn and The Tijuana Club. The Dew Drop is of course central to so many local and national stories, from the story of rock and R&B to the story of Black entrepreneurship in New Orleans to the story of the fight against segregation. The pictures in the Crawford collection help to drive home the way that queer individuals and cultures are at the heart of all of these stories in ways that aren’t always acknowledged. Could you talk a bit about how queer history is or isn’t registered in the archive, and how folks looking for queer histories within New Orleans music history might go about finding material? I’m thinking especially of some of the difficulties of translating terminology across different time periods; the photos at the Dew Drop are labeled as photos of “female impersonators” rather than as drag performers, which might make these photos difficult to find if one is using contemporary search terms. I’m also wondering about the importance of keeping LGTBQ+ figures and stories centered now, as the Dew Drop is being slated for renovation and revival in the coming year. How might some of the materials housed at the Hogan help to keep the intersections of gender, sexuality, music, and dance visible and accessible to different audiences?

Female impersonators dance contest with Patsy Vidalia (front); Bobby Marchan, M.C.; [Joe Jones ?], piano, at 2836 LaSalle Street, New Orleans, Ralston Crawford Collection of Jazz Photography, Box 3 #19, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA. https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A21695. [hi-res scan requested 1/19/2022]

MW: Part of the challenge in fully representing queer history is that it can’t be done unless a person self-identifies as LGTBQ+ or research has been done on a person to establish their LGTBQ+ affiliation, connection, or status. Fortunately, there has been great research and writing on some of the Dew Drop Inn entertainers who were female impersonators, as well as events that showcased them. Among others, entertainer Patsy Vidalia was a mistress of ceremonies at the club and also a female impersonator, and veteran Black music artist and executive Bobby Marchan also worked there as an MC, performer, and female impersonator. Anyone seeking hidden queer histories within New Orleans music culture will have to do the research and work of uncovering, while acknowledging that a queer participant may or may not have wanted to be recognized as such for their own personal reasons. Regarding the difficulty of searching for drag performers versus “female impersonators,” the same conversation comes up regarding self-identification. For example, Marchan described himself in a 1998 interview as a “female impersonator,” so it is the duty of the archive to responsibly represent how a person self-identifies while noting modern trends in reparative language, identification, and description. The onus of the wonderful work to discover hidden queer histories is on the researcher, and it’s also on us as participants in this culture to archive our lives as they’re happening because they are the materials that will make up the archival collections for people centuries from now who are studying us in the present. What’s happening now is what will be history in the future. It is my goal as an archives professional to not simply wish to collect donated materials that can help researchers with this work, but to work with my colleagues to make certain that donated materials are, therefore, discoverable and accessible. That’s done through a dedication to responsible care and collection management of materials, and attention to queer histories in collection development, in addition to community reach and engaging meaningful relationships.

Back to Issue 16 Table of Contents