An Interview with J. Aaron Sanders, Author of Speakers of the Dead

#

AN INTERVIEW WITH J. AARON SANDERS, AUTHOR OF SPEAKERS OF THE DEAD

Published June 2016

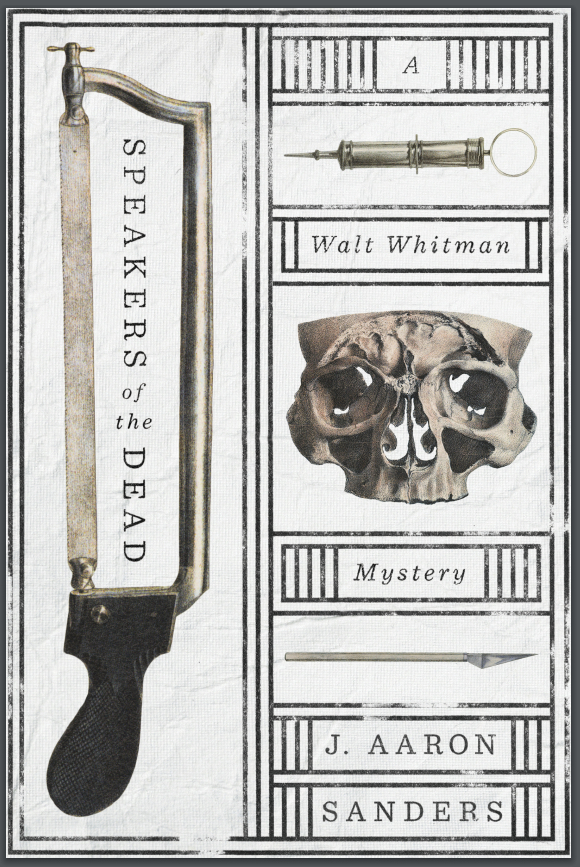

Sanders’s first novel, Speakers of the Dead: A Walt Whitman Mystery (Plume) features a young Walt Whitman as he finds himself in the middle of body-snatchers, medical students, and the law.

When NANO assistant editor Rebecca Devers learned of Sanders’s book, she was excited by the synthesis of the historical, literary, and mysterious. And she was thrilled when the author agreed to a NANO interview in the Spring of 2016.

Rebecca Devers: I want to start by congratulating you on Speakers of the Dead. The reviews are exuberant, and I have to agree that it was a fun read, if one can call a tale of corpses and corruption “fun.” I think what made it fun for me was the way the mystery plot was interwoven with what is clearly a great deal of research about nineteenth century New York City. Could you say a little about the process behind a novel like this one? I guess I’m wondering how you approached the balance of historical accuracy and creative license.

J. Aaron Sanders: I’ve said elsewhere that I researched this novel like I was writing another dissertation, and it’s true. I had that same dissertation feeling that every line needed to be backed up by research. In fact, I started researching Speakers of the Dead at the University of Connecticut when I was writing my dissertation. I spent the mornings on my dissertation and the afternoons on the novel. Half of the shelves in my library office were filled with books on violence in contemporary American male fiction writers and the other half were filled with books on Whitman and 19th-century New York. It took some time for me to wrap my head around the period before I could start writing, and even then, I would discover some detail that inflected my understanding of 1843 New York that I then had to account for in the narrative.

As for the tension between historical accuracy and creative license, that was something I had to get comfortable with. In other words, I was too aware of the tension at first and was too careful in my approach. I studied other historical novels—Hey Day by Kurt Andersen, The Alienist by Caleb Carr, and The Dante Club by Matthew Pearl to name three—and figured out that at some point a historical novelist has to step off the cliff into fiction. I noticed that while these novelists had done hardcore research, they were also having fun with the period. That was liberating. My approach is to get the historical context right and then create a story that might have occurred in it.

Devers: At times in the novel, a specific sort of “peeling-back” is described as part of the process of dissection. Walt becomes a rather unwitting witness at these revelations, and therefore so does the reader. It strikes me that this sort of vulnerable uncovering is sometimes part of the writing process itself. Did you find yourself surprised by anything you uncovered while working on the project?

Sanders: I was surprised that more has not been written about Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the U.S. to earn a medical degree. That has changed recently, and the Physician Moms Group (PMG) recently designated Blackwell’s birthday, February 3, as National Women Physicians Day, which is encouraging. That said, there is still so much work to do with Blackwell’s life and career.

A few highlights: Blackwell was accepted to Geneva Medical College when her application was thought to be a joke and the other medical students, all male, voted to accept her. She wanted to be a surgeon, but after an eye injury, she instead opened the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children that she ran with her sister, Emily, and Marie Zakrzewska. Even though Blackwell was in Cleveland in 1843 (she would move to New York City in 1851), I had to feature her in Speakers, so I used dramatic license to pluck her out of Cleveland and drop her into 1843 New York City.

Devers: In your Author’s Note, you emphasize a span of thirteen years in Whitman’s life that bridged an average career in journalism and the iconic publication of an American classic; while you admit that “Whitman’s trajectory as a writer, and his genius, owe us no explanation” (296), the novel helps to contextualize him in a moment chaotic with change. As a scholar, has your relationship with Whitman changed after writing the novel?

Sanders: Definitely. In the novel, Walt Whitman is different from the great American poet that we so often read about. He was young and ambitious, and he was living a big life in New York City. He could kick ass if he needed to—what I found fun, when writing the novel, was how human Walt became. The way we talk about Walt Whitman the Poet sometimes reduces him to a mystical hero, and to me that is less interesting than a living and breathing man struggling to reach his potential.

The most striking thing about writing historical fiction, for me, are the moments when I connect with the problems my characters face in the 19th century. In other words, my ability to relate to characters in another time illustrates the relevance of a novel set in the past. In our lives we fall in love, we hurt people, and we ourselves are hurt, something about that part of being human, and the way it stretches across history, comforts me. This happened with Walt Whitman, and despite all my scholarly research into his life, trying to get inside his head and walk around 1843 with him reminded me that he had no sense of who he would become. That’s really interesting to me.

Devers:I enjoyed the incorporation of Whitman’s (and later, Poe’s) writing into the events that take place as Walt tries to solve the mystery. Poe’s inebriated blurts provide some comic relief during the tenser moments, while the inclusions of passages from Leaves of Grass give us a glimpse of the genius that Walt is about to become. How do you envision these moments affecting the reader’s understanding of Whitman? For instance, on one hand, I can see them working to humanize him a bit, as they provide a backdrop of loss to his celebration of life. But on the other hand, it is at times so epiphanic and spiritual as to secure him more firmly in the realm of mythic genius. What do you want these moments to accomplish?

Sanders: I think you answered the question for me! The passages do both humanize and elevate Whitman. A novel featuring Whitman, it seemed to me, needed to include some of his writings. I found that using Whitman’s own words anchored the text in the 19th century. It also is a nice wink to those familiar with his work (and Poe’s), but it doesn’t detract if the reader isn’t familiar. But you said it best in the question.

Devers: Were you inspired or influenced by other writers of literary history?

Sanders: Absolutely. I’ll share four (three of which I mentioned earlier):

The Alienist by Caleb Carr

The granddaddy of them all. For me, Carr changed the game with The Alienist. A gruesome, suspenseful trip through late 19th-century New York City, full of historical detail and characters such as the young police commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt. I reread it every few years to remind myself what historical mysteries can do.

The Dante Club by Matthew Pear

The Dante Club was an important discovery for me because Matthew Pearl does perfectly in his novel what I wanted to do in my own. I love how Pearl deftly negotiates the tension between history and fiction, and I studied his depiction of historical figures such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Oliver Wendell Holmes. I also love the boldness of the conceit: a serial killer who uses The Inferno as inspiration, and a group of scholars who use the same literature to help catch him. Finally, the novel is both a fun read and an intellectual challenge. I should also note that his second novel, The Poe Shadow, inspired a subplot in Speakers of the Dead.

Expert in Murder by Nicola Upson

What I admire most about Nicola Upson’s work is the prose. It’s evocative and beautiful, and at the same time, moves the plot forward as it must in a mystery. This is not as easy as many think! Naturally, I also admire the way she treats history. I learned about possibility in the gaps of history. I admire the way she has dealt with these challenges of the historical mystery genre, and she has been a good model for me as I write.

Hey Day by Kurt Andersen

What I admire most about the novel is how precisely and evocatively Andersen has painted New York in the mid-19th century—from places to sounds and from smells to speech patterns. My favorite moment is when Walter Whitman lumbers into Joe Orr’s saloon. The portrayal is dead on, from the physical description—“loose tie, a big lopsided grin, and huge eye brows arching over bright blue eyes”—to Benjamin Knowles’ playful moniker “Franklin Evans” to Whitman’s lively way of speaking. But more than that I think Andersen’s portrayal of Whitman illustrates the very thing that elevates Heyday above other historical novels: a broad-sweeping but intimate verisimilitude that celebrates history without relying too heavily upon it.

Devers: Will we see Walt at work again on another mystery?

Sanders: Yes! I’m hard at work on the second book in the series, which follows Whitman and his brother, Jeff, down to New Orleans where they become involved with an escaped slave, his vindictive master, and slave-trading pirates.

Devers: How exciting! Do you have a working title yet for the second book?

Sanders: Yes! The Blood of a Gentleman.

Devers: I can’t wait to see Walt in action again!