Crafty Bricolage: Pinterest as Digital Scrapbooking

by Maura D'Amore

Published December 2016

“As a kid I was a bug collector,” remarked Pinterest co-founder and CEO Ben Silbermann in his 2012 Altitude Design Summit keynote address. “I’d always thought that the things you collect say so much about who you are.” As he spoke, an image of a child’s bug collection, with yellow pins stuck through each specimen, appeared on the screen behind him with the heading “Pinterest 1.0” at the bottom corner of the page.

I’m struck by this image and by Silbermann’s attendant narrative, with his suggestion that the collecting impulse marks us as human, and with the way in which he roots that impulse in the geographies of childhood. This essay is a meditation on Pinterest as a platform for collecting and organizing desires, an inquiry into how the site negotiates the dialectic between having and being, looking and doing. As an academic with interests in the history of American literary and visual culture, I want to think about what Pinterest has in common with the curiosity cabinet and the scrapbook in the nineteenth century. What did individuals seek to preserve and communicate about themselves and about their environments through those mediums, and to what extent do those motivations map onto this technology? As a parent of two small children who appreciates Pinterest as a place to catalog possible art projects, I’m interested in the relationship between inspiration and creation: how does the platform foment and channel consumer desire while billing itself as a design-minded outlet for savvy self-expression? How frequently and in what shapes do my pins and boards translate from screen to table or yard?

In her book on cultures of scrapbooking, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance, Ellen Gruber-Garvey casts scrapbooking as a form of writing, a genre that “embodie[s] … aspirations” and “ma[kes] them a good deal more portable” than they would otherwise be (3). Her use of the verb writing suggests a creative impulse and makes the claim that the act of selectively cutting and pasting images and text created by others can become its own form of creative expression. In doing so, she asserts that all text (and all experience) is copy, and that any artistic production cobbles and tinkers with things that are already in circulation. She also comments on the process by which scrapbooks allowed individuals to “dignify [their] clippings with the prestige of the bound book” (3). Linking the predicament (addressed by the scrapbook) of nineteenth-century readers with those of the twenty-first century, Gruber-Garvey states,

Like present-day users of the web, blogs, Facebook, and Twitter, these readers complained that there was so much to read that they were constantly distracted. Nineteenth-century readers felt inundated by printed matter … Newspapers constituted a new category of media: cheap, disposable, and yet somehow tantalizingly valuable, if only their value could be separated from their ephemerality. How to keep up with all that information, assess it, and find it again when needed?” (3-4)

Whenever I read this account by Gruber-Garvey, Pinterest is on my mind. It’s obvious that she was not aware of the platform when she published the book in 2013; she mentions “favorite lists, bookmarks, blogrolls, RSS feeds, and content aggregators” (4), but is silent on Pinterest, a content management system that arguably trumps the ones she mentions precisely because it behaves more like a scrapbook and encourages users to dignify their pins in a different way. In the following paragraphs, I clip parts of Gruber-Garvey’s introduction and recirculate them in my own act of creative processing and possession; in applying her arguments to my experience of Pinterest, I hope to extend her arguments and present parallels between old and new platforms for speaking selfhood through assemblage and recirculation.

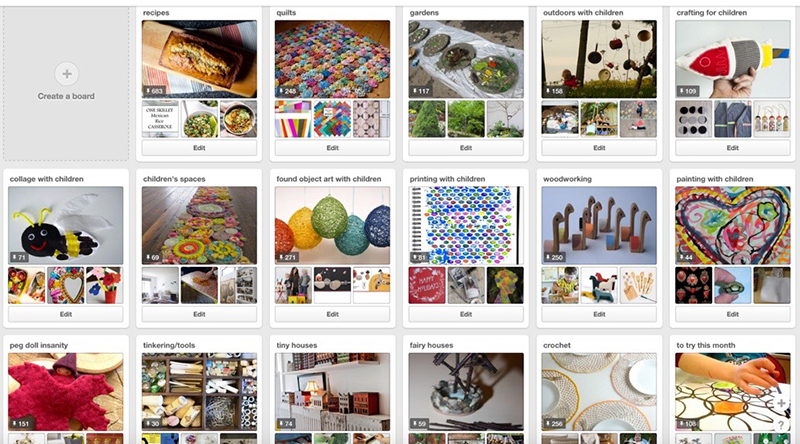

Gruber-Garvey acknowledges that “in a sense, newspaper clipping scrapbooks were simply filing systems” (4). Similarly, Pinterest can be viewed as a virtual filing cabinet. Pins correspond to clippings and boards with folders; folders can be rearranged and re-labeled visually and textually, and pins can be moved between boards or copied into multiple boards. I have 97 boards, most, but not all, of which are related to art-making and play with children.

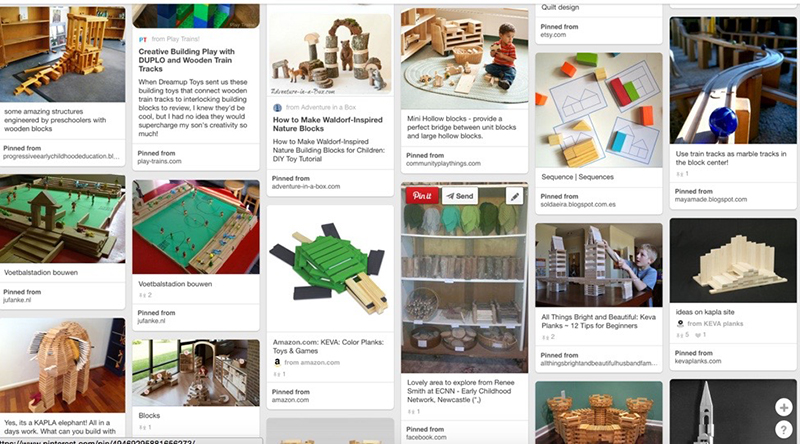

Once inside a board, the format reverts to older content management systems: newest pins are up top, oldest at the bottom of the scroll. Like file folders, the boards themselves risk becoming unorganized, a problem Pinterest has recently recognized and attempted to remedy by making it easier to move and delete batches of pins. As with the curiosity cabinets of nineteenth-century naturalists, Pinterest boards rely upon and reproduce conventionally accepted taxonomies while recognizing and providing an outlet for the particular affective rationales of the individual doing the organizing. My “block play” board, for example, mixes pins related to products I’d like to purchase, unconventional uses for blocks I already own, structures to copy, and block station set-ups.

This flexibility reinforces the idea that the activity of pinning itself is creative, a generative (because idiosyncratic) variety of mental housecleaning.

Unlike traditional filing cabinets, Pinterest boards are available for browsing and copying by strangers. They are public by default, and the larger and more active the pool of pinners, the broader the content from which other pinners can draw. By adhering to recognizable tags, users perform a service to the larger community by making their boards and pins more search-friendly. Like nineteenth-century scrapbooks and curiosity cabinets, I build my boards to satisfy my own whims, but I simultaneously am aware of myself as part of a larger group of hobbyists. The sense of community I experience feels more neoliberal in this case, though. I skim and scan my feed discriminatingly and attempt to improve the application’s algorithm of customized pins by carefully curating the boards and individuals I follow. The Pinterest community exists, in my mind as a user, to provide me with artistic and experiential provocations that match my interests and aesthetics—ideally, better than a single magazine or blog. I spend time identifying other users who are similar to me, but with rare exceptions, my interest in them as people is limited to what they can do for me: whether we overlap in interests and aesthetics, and whether their boards offer me new content to mine. As a pinner, I am grabby and colonialist, but also relatively anonymous and flitty. I recognize that I function in a similar way for other users, and I am relieved that I do not have to think about them while I am on the site. Pinterest tells me that I have a total of 49,000 pins, and that 644 users follow one or more of my boards. I find it telling, though, that I rarely pay attention to who those users are or which of my pins are most popular. All of my pins came from another user, after all, and since I don’t have a monetary stake in any of my Pinterest activity, I have little interest in my sphere of influence and feel no sense of obligation to the community or to the platform as a contributor, even as I recognize that sphere might be valuable to a company.

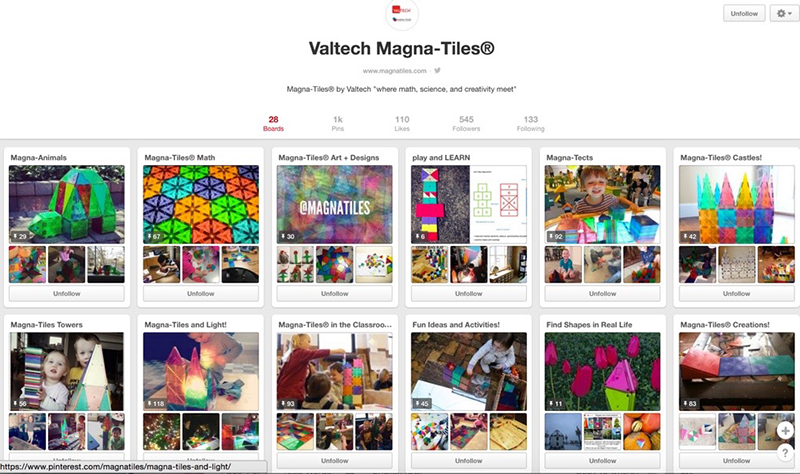

At the same time that the site encourages me to conceive of myself as master of my boards, I recognize my de-facto role as an ambivalent operative. By agreeing to the site’s terms, I implicitly acknowledge and perpetuate a corporatization of creativity. Silbermann carefully avoided any mention of companies or marketing in his Alt Summit talk, but it’s no secret that his business model is profitable and that Pinterest users are embedded in—and cognizant of—market sensibilities and practices. In one sense, this is nothing new: in the nineteenth century, companies certainly profited on the scrapbooking craze and advertised their services in the very periodicals from which readers clipped. Like scrapbookers, though, pinners implicitly understand their identities as consumers as multivalent and potentially enriching. Today, many companies recognize branding and marketing opportunities in maintaining their own Pinterest accounts. If a brand has particularly active boards and exciting tutorials, I may find myself more likely to support it monetarily down the line. Like companies in the nineteenth century who began to tailor their advertising images to scrapbooking aesthetics, twenty-first century businesses can introduce targeted pins to the site, which can lead to increased traffic and revenue, especially if they pay for their pins to appear in the feeds of customized demographics.

However, they are also compelled, by the maker ethos of the site which I’ll discuss in more detail below, to picture new uses and settings for their products, as in the case of Valtech, a company that sells a magnetic block system called Magna-Tiles.

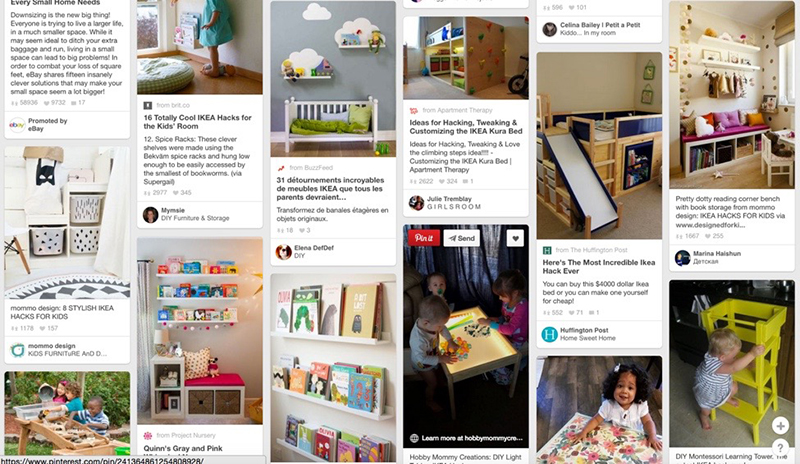

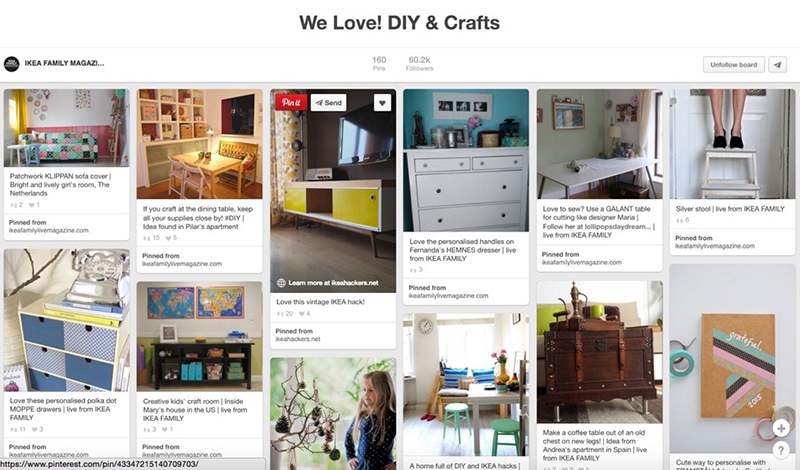

Companies outsource some of their advertising to their consumers, who post photos of themselves using products in creative ways. In order to do so they have to recognize, even on a small scale, the buyer as designer. The platform, in other words, encourages both companies and individuals to conceive of themselves as influential creatives. Products are recast as tools, starting points for self-fashioning, and if companies encourage and publicize hacking, they might be rewarded by wider markets and more sales. There are many “Ikea hack” pins on Pinterest, for example; by maintaining their own “hack” boards and wrapping their products in cozy visual and textual narratives, though, Ikea compliments consumers for their ingenuity and encourages them to take possession, affectively, of mass-produced objects.

So, sure, savvy companies use Pinterest to co-opt users into becoming unpaid marketers. Users, in turn, gain a powerful consumer platform for suggestion and critique. They also, significantly, begin to conceive of market goods as raw materials—just as scrapbookers began to think of periodicals—for the creation of stories they craft themselves.

Silberman claims that the company’s mission is “not to keep you online, but to get you offline,” to “inspire you to go out and do the things you love.” By casting his online application as mapping paths to offline activity, he sidesteps the reality that the site is a goldmine for marketers. While it’s wise to be wary of his fantasy of Pinterest as a platform that allows users to free themselves from established webs and make new memories and narratives, it also seems clear that he originally founded Pinterest to help realize this goal. Gruber-Garvey links scrapbooks to a “shift to a more widespread understanding that newspapers held fragmented information that could be remade in other configurations,” which she identifies as “crucial to our present-day understanding of information” (9-10), and Silbermann’s comments suggest he is excited about this sort of remixing. He admits that he loves when people use the site in ways he hasn’t anticipated.

While nineteenth-century scrapbookers certainly clipped plans for the future—perhaps most widely, those associated with recipes, health remedies, fashions, décor ideas, and garden plans, they more frequently sought to record and memorialize past experiences, friendships, and thoughts. In that way, scrapbooks functioned as visual diaries and were sometimes described as “an analog of a life itself,” according to Gruber-Garvey (11). Pinterest, too, seeks to function as analog self, but as an aspirational self that aligns most closely with the first category of scrapbookers described above. I conceive of most of my pins and boards as bookmarked prompts, ideas I don’t have the time or mental space to fully grapple with now but to which I anticipate my future self wanting access.

Although I have one board that records past occurrences (my “garden” board, where I pin information about plants I’ve already planted in my yard, for future reference), those records mingle indiscriminately with future ideas and plans. For the most part, once I’ve tried an activity or project related to something I’ve pinned, I delete the pin. I don’t need a record of it: the activity itself, or in many cases, the craft or art object that results from the activity, becomes the only record I value. Silberman associates the platform’s ethos with inspiration rather than documentation, a prioritization which is reflected in common practices of pinning.

While scrapbooks deliberately foreground the identity of their creators, who in turn determine how and where they circulate, Pinterest boards are more lax when it comes to questions of ownership and attribution. Gruber-Garvey reminds us that scrapbooks’ compilations constitute a performance (15), but that they “may express only a partial view of their makers’ identities” (17). While the latter characteristic is amplified in the case of Pinterest boards—I do not share any identifying personal information publicly, for instance—the element of performance is muted for users unless they stand to gain monetarily by impressing other users. While a scrapbook or curiosity cabinet “performs archivalness,” to use Gruber-Garvey’s term, both the genealogy and intended duration of Pinterest archives are more ephemeral. Somewhat ironically, the platform privileges originality but devalues ownership of ideas or methods. Indeed, a major attraction of the site lies in its deconstruction of originality. The “source” of pins frequently only becomes apparent by clicking on the pin itself and discovering where the site reroutes you. In terms of longevity, pins essentially disappear in the feed when a board becomes too big. They are only potentially valuable, and once they have asserted their value by being “used” in some way, they cease to have power or interest for the original user, and if they aren’t deleted, only exist to be discovered and pinned by a different user.

I can say, honestly, that I use the site in ways that align with Silbermann’s stated mission. I do a lot of sewing, and I typically peruse my quilting and softies boards for inspiration.

Sometimes I follow one tutorial or copy a particular design, but more frequently I find myself opening multiple pins in separate tabs and using them as visual guides to my own work. Before certain holidays or seasons I peruse applicable boards to identify a craft or two I’d like to try with my children in the coming weeks. I consult my recipe board frequently and incorporate 1-2 pinned recipes into our dinner routine on most weeks. I followed pinned instructions to learn how to re-string my guitar, clean my bathroom with natural ingredients, free-motion quilt with my sewing machine, and operate a scroll saw. When my husband and I decided to build a treehouse in the backyard, we pinned designs and tips onto my “outdoors with children” board, and the instructions we found there were more helpful and accessible than the book we bought. When possible, I prune my boards to prioritize projects I might actually try. It gives me pleasure to scroll through my pins: the layout of the site, which frames each pin almost as an art object, contributes to my awareness of myself as a curator.

I am aware that the site does not function in the same way for all users, though: a 2013 NBC Today feature reported that, according to a survey, “‘Pinterest Stress’ Affects Nearly Half of Moms” (Dube). Arguing that the site ratchets unrealistic expectations for mothers, especially, to host elaborate parties, make their own playdough, construct custom playscapes from scrap materials, mix their own cleaning solutions, and set out enlightening “invitations” for their children to play on a daily basis, critics suggest a downside for women, in particular, of a space where there is such a distance between display-oriented felicities and the routine necessities of everyday life. Certainly, pinning can serve as an end in itself. That’s great if it brings the pinner satisfaction, but there is a fine line, as the example of Martha Stewart makes clear, between being inspired by beautifully imagined and catalogued images and projects and experiencing frustration with the perpetuation of unrealistic expectations and desires. The latter relationship to the site can be intimidating and demoralizing: the sheer number of pins combined with the wide range of ideas can lead to feelings of inadequacy. Pinterest fails, though, have their own pleasures, or at least narratives of other people’s less-than-successful results do. On the website Pinterest Fails (subtitle: “Where Good Intentions Come to Die”), readers can compare the original pin with a user’s attempt to replicate it. In addition to images contrasting the “fail” with the model, submissions narrate “the grisly details” of the failure. Even then, the “next time I will” section of each entry suggests that there will be a next time (!) and offers tips from the trenches.

Hearteningly, the ubiquity of the phrase “Pinterest fails” itself confirms the existence of active sub-groups who feel empowered enough to joke about discrepancies between the image and reality of Pinterest performance. Humor can operate as a form of catharsis and alt-community formation. One need only look at the success of Amy Sedaris spoofs of Martha Stewart (I Like You: Hospitality Under the Influence and Simple Times: Crafts for Poor People) to see how this process works. To its credit, Pinterest allows space for a playful, tongue-in-cheek orientation to its content: many Pinterest users maintain “Pinterest Fails” and “Future Pinterest Fails” boards. This fact also suggests that at least some users are not intimidated by the prospect of failure, or have brought with them a flexible understanding of what constitutes success to them.

Still, articulations of discontent and disillusionment should not be shrugged off, especially as they point towards Pinterest’s collusion in (and profit from) a larger trend, namely the unsettling gendered politics of the Maker Movement. Like the online marketplace Etsy, Pinterest speaks the language of DIY/maker culture, a twenty-first century movement that uses technology to marry a handmade, crafter aesthetic conventionally associated with women’s domesticities with an engineering, tinkering bent typically linked to masculine leisure pursuits. In her 2015 article for the Atlantic, “Why I Am Not a Maker,” Debbie Chachra problematizes the Maker Movement’s identity politics, namely, what she sees as a gendered, elitist valorization of a “creator” over those whose contributions to their families and communities are of a different order. She is especially interested in the movement’s disregard for practices of caregiving, which she sees as supporting the “makers” in myriad under-recognized ways. She remarks that “an identity built around making things—of being ‘a maker’—pervades technology culture. There’s a widespread idea that ‘People who make things are simply different [read: better] than those who don’t.’” Furthermore, she asserts that “while the shift might be from the corporate to the individual (supported, mind, by a different set of companies selling a different set of things), it mostly re-inscribes familiar values, in slightly different form: that artifacts are important, and people are not.”

In reifying the artifact, an activity of capturing and trading the final tangible product upon which the platform is built, Pinterest participates in the active denial of the invisible labor involved in creating it. More quietly, like the Maker Movement, it perpetuates a (historically gendered) divide between those who make and those who create conditions which facilitate the making (cleaning, tending, cooking, teaching, maintaining, mending). In the words of Ashley Reed, “the Maker movement, despite claims to embrace craft and domestic activities like sewing, gardening, and cooking, obscures and even denigrates the care work that stands behind and enables Making—care work most often performed by women” (24). While Pinterest pays lip service to the domestic cares, desires, and aspirations of the women who comprise its primary user base, the structure of the site systematically downplays their identities as anything other than pinners whose value lies in their circulation of pins. Because its audience is overwhelmingly female, Pinterest stands as a fascinating example of the sorts of challenges and contradictions that emerge when someone attempts to extend the hallmark tenets of maker culture to a population whose identities don’t map neatly onto its relatively esoteric articulation of what, exactly, constitutes a maker… or what else a maker might be. The packaging and privileging of the pin and the folly of treating pinners like a monolith are all the more troubling as the site’s ties (and those of the Maker Movement more broadly) to corporate culture become increasingly visibly integrated into its design and “suggested pin” algorithms. In 2015, Pinterest introduced “picked for you” pins to user feeds, and in doing so, much to users’ chagrin, turned much of the self-making it claimed to cherish over to the machine.

One thing is clear: the status and identity of the pinner, for Pinterest, is fraught. On the one hand, the site pushes the boundaries of conventional understandings of what constitutes making by suggesting that pinning itself might constitute a creative act. It also encourages users to conceive of themselves as design-savvy creatives, tinkerers who cobble together ideas and customize projects to suit their own whims. On the other hand, it devalues the human component of any making that goes into what ultimately becomes the pin and insinuates that the minds of pinners are predictable (and co-optable). The fact that Pinterest sends mixed messages to pinners demonstrates the potential pitfalls of the Maker Movement’s drive to populate, and haste to celebrate, what Mark Hatch in The Maker Movement Manifesto calls “the Internet of Things.” Pinterest’s demographic is a problematic one for maker culture because in many cases it requires a different understanding of what constitutes meaningful labor, specifically what to make of labor without an identifiable end-product. The premise of Pinterest, as a site that celebrates activities of (mostly domestic) preparation and organization as aesthetically pleasing and creatively engaging, has the potential to work around narrow definitions of “makers.” It is built around faith in packaging, in the promise of future pleasures, and acknowledges that empty time of making ready is not only not empty but is integral to the mechanics of daily life. In practice, though, it too often falls short of its stated goals, and in doing so reproduces limiting stereotypes about female domestic consumers.

How do we reconcile Silbermann’s hope that Pinterest be “the most beautiful place … to plan the most important projects of your life” with a recognition, in Reed’s words, that “the new incarnation of the commercial Maker movement has less to do with the pleasures of creation and collaboration than with the possibility of gain” (26)? How can users hack the maker movement? In the introduction to their edited collection DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media, Matt Ratto, Megan Boler, and Ronald Deibert recognize the presence of

large numbers of “modders,” hackers, artists, and activists who redeploy and repurpose corporately produced content or create novel properties of their own, often outside the standard systems of production and consumption. This activity is not relegated to the sphere of the digital but also includes communities of self-organized crafters, hackers, artists, designers, scientists, and engineers. These groups are increasingly to be found online exchanging sewing and knitting patterns, technical data, circuit layouts, detailed electronics tutorials, and guides to scientific experiments, among other forms of instruction and support. (4-5)

Returning to the scrapbook of the nineteenth century—whose creators were political in their very resistance of more enshrined understandings of originality, creation, and identity—might help us see a potential for pinners to bend and subvert Pinterest as they see fit. While the platform is flawed in certain ways, it offers a starting place. What are we as we pin, after all, if not bricoleurs, individuals who construct something new from diverse, sometimes defective or obsolete, typically commercial materials and sources? Bernie Herman reminds us that “the bricoleur's discovery of meaning is always imaginative and personal: the sense and communication of meaning is inescapably contextual and always about the relationships established between people and their environments in all of their many intimacies” (39-40). We all gather, organize, critique. These activities are their own sort of scene setting, a fledging that is at once a learning how to make do, an activity (the activity of life, arguably) of assembling an identity from pieces already in circulation.

Works Cited

Chachra, Debbie. “Why I Am Not a Maker.” The Atlantic. 23 Jan. 2015. Web. http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/why-i-am-not-a-maker/384767/. 18 Apr. 2016.

Dube, Rebecca. “‘Pinterest Stress’ Affects Nearly Half of Moms, Survey Says.” Today: Parents (NBC), 9 May 2013. Web. http://www.today.com/parents/pinterest-stress-afflicts-nearly-half-moms-survey-says-1C9850275. 17 Apr. 2016.

Gruber-Garvey, Ellen. Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford UP, 2013.

Hatch, Mark. The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2014.

Herman, Bernie. “The Bricoleur Revisited.” American Material Culture: The Shape of the Field. Eds. Ann Smart Martin and J. Richie Garrison. Winterthur, DE: distributed by U Tennessee P, 1997; pp. 37-63.

Ratto, Matt, Megan Boler, and Ronald Deibert. DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. Cambridge, US: The MIT Press, 2014.

Reed, Ashley. “Craft and Care: The Maker Movement, Catherine Blake, and the Digital Humanities.” Essays in Romanticism 23:1 (2016): 23-28.

Silbermann, Ben. Alt Summit Keynote Address. Salt Lake City, UT, 2012. https://about.pinterest.com/en/files/ben-silbermann-keynote-address-alt-summit