Editors’ Introduction for NANO Special Issue 12: Star Wars: The Force Awakens: Narrative, Characters, Media, and Event

by Jason W. Ellis and Sean Scanlan

Published December 2017

“Star Wars . . . will undoubtedly emerge as one of the true classics in the genre of science fiction/fantasy films. In any event, it will be thrilling audiences of all ages for a long time to come.”

-Ron Pennington, The Hollywood Reporter, 25 May 1977

“It won’t be a new world, not the way it was in 1977. It’s not like we’ve never seen this Jedi mind trick before. In a sense, Abrams is restaging a revolution that already happened, decades ago. But while The Force Awakens won’t have the element of surprise, it does have another advantage, which is that even without having seen it, people already love it.”

-Lev Grossman, TIME, 14 December 2015

Between 1975 and 1980 a collision of transmedia stories collided in my head which led to my fascination with The Force Awakens. My story begins, as many do, by misdirection and mistakes.

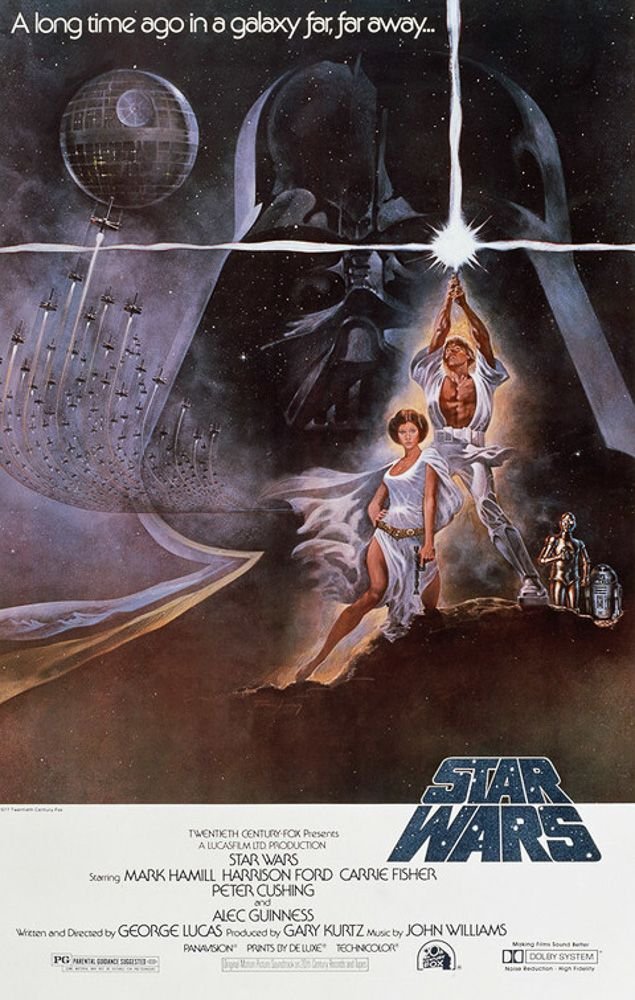

When I was ten, I was going to be, by turns, an astronomer, astronaut, and test pilot. The first three school papers that I was proud of and that I have kept to this day were on Johannes Kepler, nuclear fission and fusion, and the fastest jet on the planet: the SR-71. [Aside: The only magazine we received at my house was Aviation Week and Space Technology.] These influences and my career dreams made me an easy target for the Star Wars movie poster.

The poster called to me not because of two main characters, the two droids, and not even because of the massive background-swallowing ghosted image of Vader’s helmet. It was the Death Star, the X-wing starfighters, and space itself. That one movie poster revealed a universe more advanced and more dangerous than my own; I desperately wanted to visit this place, or at the very least, I wanted to see it. But I could not. The reason I could not was because of what I call the Jaws fiasco.

Ever since the Jaws fiasco of ‘76, my parents were hesitant to let me see a scary movie or anything science fictional. I was eight when my parents took me to see Jaws. Actually, they went, and I promised to sleep. I was holding onto my fake promise until that shark tooth and eye-ball scene, and that is when my parents realized I was not asleep. A good loud scream has that effect. So, my parents put the kibosh on those movies for a while, until I left for college or so they said at the time.

Some readers might find it ironic that Richard Donner’s Superman and Matthew Robbins’s Corvette Summer (both 1978) enabled me to see Star Wars. After I handled those two films well, I convinced my parents to let me see Star Wars.

It is worth noting how I was able to see Star Wars at such a late date after the film’s original release in 1977. Unlike today’s blockbuster films released on a synchronized date across thousands of screens followed by carefully orchestrated DVD, Blu-Ray, digital download, and streaming launches, Star Wars first appeared at only 32 theaters, but it eventually opened at cinemas across the United States over an original 18-month release. There were several revivals leading up to (and following after) the release of The Empire Strikes Back on May 21st, 1980. It was in one of these theatrical re-releases that I seized my opportunity.

On or about March 24th, 1980, the space-time continuum changed direction. My mom gave in to my unceasing requests to see Star Wars. But she had one condition. She would sit at the very back of the theatre, and she would read her book. I may sit no farther than ten rows from her. And, importantly, she would need her ‘lightsaber’ back. I had stolen her lightsaber-like flash light a while back; it was perfect for under-the-covers, bed-time reading. With this agreement in place, we drove to the St. Andrews Cinema in St. Charles, Missouri. I could barely manage to walk or talk; I was in the tunnel vision of impending glories I could hardly imagine. During the show, I glanced behind me to make sure my mom was still there. I was afraid the movie would be too much for her. Yes, and to make sure that she didn’t leave me alone to face the trash compactor, the sound of the TIE fighters, and that breathing noise Darth Vader made. Since the theatre was nearly empty, no one was bothered by my mother’s lightsaber.

I was not among the first of my friends to see Star Wars, and so their stories of the movie combined with what I had read about it. The sharing of stories about Star Wars—whether from the film or its many transmedia expansions, supplements and transformations, including radio dramas, action figures, books, magazines, television specials, and games, seems to be a universal aspect of the Star Wars experience. Peter Krämer, in asking his students in a course on Spielberg and Lucas about the influence of Star Wars on their lives, reports:

[T]hey had all been aware of Star Wars. They had seen the films, often in the wrong order, on video (regular or pirate) or TV or at the cinema during one of numerous re-releases; and, more importantly, they had listened to the soundtrack, read the books, played with the toys, dressed up as the characters, acted out scenarios from the films and invented new ones. Even the few students who did not like Star Wars said that their childhood had been completely overshadowed by it, that the saga's characters, stories and catch phrases had been a primary reference point for their peer group and also within their families. (Krämer par. 5)

While Krämer’s observations come after the release of the Star Wars prequels and before The Force Awakens, the operation of transmedia elaborations and audience engagement that is ubiquitous today was established during the era of the original trilogy. The many layers of transmedia storytelling associated with Star Wars—from soundtrack listening to costumed play—invites the audience to immerse themselves in this fictional universe as spectators and participants. With so many kinds of transmedia experiences possible within the orbit of Star Wars, it is not surprising that it would overshadow the childhood experience (and probably adult experiences, too) of self-identified fans and outsiders.

Observations of the Star Wars transmedia experience extend back to the beginning of the saga. As early as 1982, Jill P. May writes about the connection between the films, books, and Kenner’s action figure line:

Another big seller, Star Wars tie-ins, has shown that in the US toy market, motion pictures, books and toys do sell each other. A close friend of mine is a fifteen year old Star Wars fanatic who has seen both of the first two movies at least five times each . . . Rob was reading his Star Wars paperback, I teasingly said that I thought the love scene between Hans Solo and the princess was great. Rob looked up and said, “The book has lots more that are better. There's a lot happening in the book that never happens in the film. You should read it.” Star Wars figures are among the best selling of all toys. One Kenner expert explained that there are over fitty different Star Wars Figures and that “there are kids whose mission in life is to own them all” (6)

May’s anecdotal account is illustrative of a larger phenomenon surrounding the transmedia aspect her Star Wars fanatic enthusiastically offered about the novelization: “lots more that are better.” Star Wars transmedia deepens the films’ narrative in interesting and inventive ways, of course, authorized by Lucasfilm (and now, Disney), and creates points of engagement for its audiences that envelop the spectrum from passively watching a film to actively playing an imagined scenario with action figures. Deepening and broadening the storytelling possibilities through transmedia continues to play an important role in the continuing Star Wars saga now helmed by Disney.

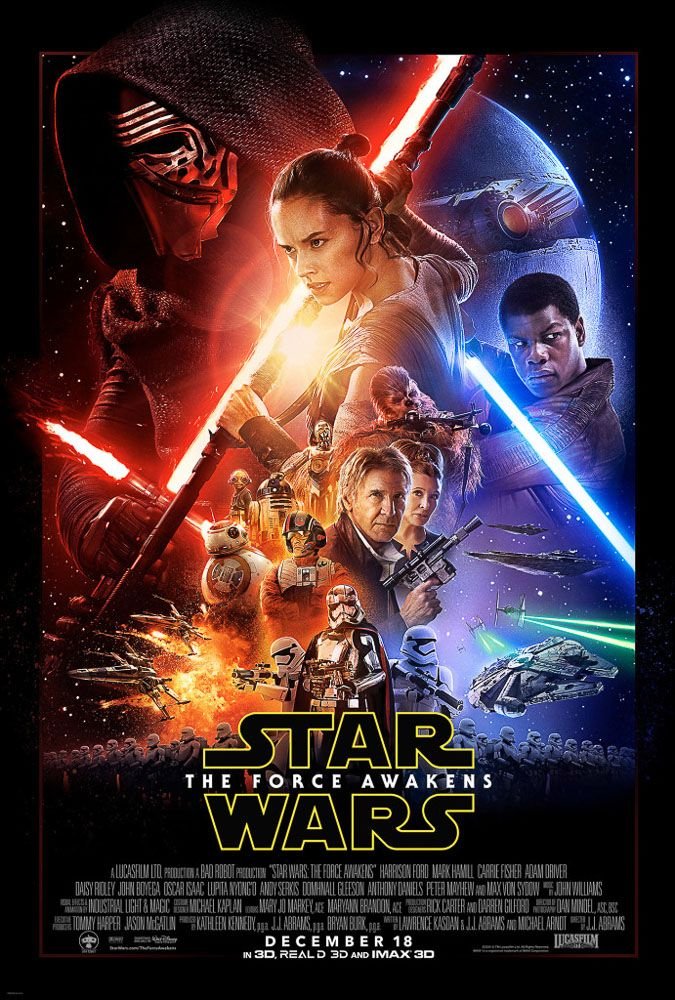

When The Force Awakens came onto my radar, I knew it was to be a moment in history in which childhood and the present came together for millions of people. To be honest, The Force Awakens is better than A New Hope because it enables older viewers an existential catch-up, perhaps in a better way than 1999’s debacle of The Phantom Menace. These viewers feel themselves to be both young and old at the same time; they witness themselves feeling young and knowing the back story, and they also witness the present as the older characters are still alive (for a moment) and thus the experienced Long Time Ago is pushed into the here and now. Simply put, TFA enables viewers to close the distance between their present self and their younger self. It makes people feel young, even if they are new to the Star Wars universe. That is, until the last scene.

The Force Awakens enables, even fosters comparisons: is Rey a worthy hero? Is Finn believable as a once-Stormtrooper turned good resistance fighter? Is Kylo Ren anywhere close in power and ability to his role model, Darth Vader? Readers can glean my opinion from that evaluative sentence. Are the scenes parallel to earlier movies? This movie, the new characters, the new poster, the toys, the novelization (by Alan Dean Foster, the science fiction writer and film novelization specialist who served as ghost writer for George Lucas’ Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, 1976, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens, 2016), and the countless viewing parties, the information sites such as Wookieepedia, and wonderful spoofs such as YouTube’s Bad Lip Reading enable me to say that this film is far beyond simple nostalgia and money-making scheme—though both of those are in play here.

It is not the completeness and closure of The Force Awakens that compelled the editors to select that movie and those experiences for a special issue. Instead, it is the excitement that this jump-start has created. The structure at the center of the Star Wars universe has held, and the future looks bright for more new characters and also more wars. The battle for political and economic control on Jakku has something to do with our current Earth-bound problems about inequality and migration and war. But more locally, for Issue 12, questions about identity come to the fore: Who gets to create new Star Wars characters? Who gets to play those new characters? Who gets to play with storylines? Who gets to be the hero and villain? Who gets to voice opinions about the new shape of the First Order? These questions lead to “how” questions—especially how should new viewers and readers understand The Force Awakens. These questions motivate the four articles and one interview in this special issue.

Threading together these questions is the transmedia storytelling of Star Wars broadly and The Force Awakens specifically. By transmedia storytelling, we use Henry Jenkin’s definition: “Stories that unfold across multiple media platforms, with each medium making distinctive contributions to our understanding of the world, a more integrated approach to franchise development than models based on urtexts and ancillary products” (Convergent Culture 293). The story of Star Wars has unfolded across different forms of media, each of which encouraged different kinds of audience engagement from passively watching the film to actively guiding the story in video games. George Lucas avoided having the original Star Wars film itself be an urtext in the sense of it being an unchangeable, original point of origin. For example, the Star Wars film novelization preceded the film’s release by almost seven months, and the film went through many minor variations (different prints with slightly different dialog during the years of initial release) and major revisions (Greedo notoriously shoots first in 1997’s Star Wars: Special Edition).

Another way to frame transmedia storytelling is by drawing on what Andrea Phillips calls, “West Coast-style transmedia,” which she defines as:

more commonly called Hollywood or franchise transmedia, consists of multiple big pieces of media: feature films, video games, that kind of thing. It’s grounded in big-business commercial storytelling. The stories in these projects are interwoven, but lightly; each piece can be consumed on its own, and you’ll still come away with the idea that you were given a complete story. (13)

Perhaps this is one of Star Wars’s and specifically The Force Awakens’s strengths. While there is the commercialization involved in selling these stories, Star Wars’s transmedia are largely self-contained. Like the earlier Flash Gordon film serials of the 1930s, audiences are brought up-to-speed with the opening crawl, and often, many points of contact or clues are included connecting one story medium to the others. General audiences take away an experience of the story and fans connect the dots forming the larger constellation of storytelling taking place across these different media. West Coast-style transmedia works when it is carefully managed. When Lucas still led Lucasfilm, he exercised control of the transmedia narrative of Star Wars, even according to Chris Cerasi of LucasBooks, “[working] quite closely with the novel authors” (qtd. in Sansweet par. 4). Now, under Disney, Lucasfilm’s Story Group performs a similar function: “The story group, which numbers 11 people, maintains the narrative continuity and integrity of all the Star Wars properties that exist across various platforms: animation, video games, novels, comic books, and, most important, movies” (Kamp par. 26). Each orchestrated medium sustains the story as an on-going emergence of narrative. Each expands the story, deepens the audience’s understanding, and raises new questions to be answered in subsequent storytelling in the same or other media. However, what we discover in some of the articles in issue 12 is that while the top-down enforcement of transmedia storytelling is a large concern, there is also the bottom-up aspect of participatory culture that adds to transmedia storytelling in ways that are not as easily controlled or contained, or as Henry Jenkins explains in Textual Poachers:

[F]ans become a model of the type of textual “poaching” de Certeau associates with popular reading. Their activities post important questions about the ability of media producers to constrain the creation and circulation of meanings. Fans construct their cultural and social identity through borrowing and inflecting mass culture images, articulating concerns which often go unvoiced within dominant media. (23)

The Force Awakens offers many possibilities for extending transmedia storytelling in ways meaningful to its audiences that Disney and Lucasfilm cannot or will not formulate. We suspect that this aspect of transmedia storytelling is a careful balancing act on the part of Star Wars’s stewards. It is in their best interest to cultivate as wide an audience as possible, and to push into the future without alienating either old or new audiences, including those heavily invested in participatory culture such as fan fiction writers and readers, such as the Viacom/Paramount crackdowns of the mid-1990s and mid-2000s on Star Trek fandom online or the tension between Harry Potter fans and Warner Bros as the adapter of J.K. Rowling’s work for the screen (positive in the case of approval for a fan film or negative for the delayed release of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. For the time being, it seems that Disney and Lucasfilm recognize the value of this additional form of transmedia storytelling in which, “Fandom . . . becomes a participatory culture which transforms the experience of media consumption into a production of new texts, indeed a new culture and a new community” (Jenkins, Textual Poachers 46). Perhaps luckily so, because the editors see so much potential in the transmedia storytelling of The Force Awakens as a collaboration—something that goes back to the beginning of Star Wars with fandom’s embrace of these transmedia stories. And, these essays are in kind a part of that collaboration, too.

Contributors to this special issue attend to questions and issues raised in The Force Awakens from an impressive spectrum of approaches. This issue begins with Cait Coker and Karen Viars’s “Welcoming the Dark Side?: Exploring Whitelash and Actual Space Nazis in TFA Fanfiction,” which discusses the overwhelmingly skewed number of fanfiction ships, or fan-created stories about relationship between fictional characters not present in the inspirational text, about Kylo Ren and General Armitage Hux. Coker and Viars argue that the popularity of ships about these two characters represents a form of whitelash in popular culture. To support this claim, they discuss ships relating to The Force Awakens, and explore these fan-originated stories through lenses of race and sex. Also concerning the transmedia of fandom and fanfiction is Chera Kee’s “Poe Dameron Hurts So Prettily: How Fandom Negotiates with Transmedia Characterization.” Kee’s focus is on the type of fanfiction known as hurt/comfort, which are stories that respond to the physical or mental pain experienced by a fictional character, in this case the stellar Resistance pilot Poe Dameron. However, Kee goes beyond fandom to reveal the correspondence between depictions of Dameron’s pain in official transmedia sources, such as The Force Awakens film and comic book, and hurt/comfort fanfiction. She concludes with an analysis of reasons why there is a preponderance of Dameron-based hurt/comfort fanfictions.

Shifting from the collaborative potential of transmedia to one of indoctrination, Simon Orpana presents an extended argument in “Interpellation by the Force: Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses in The Force Awakens” that J.J. Abrams’s film and the beginning of a new trilogy inscribes its audience in an ideology of Star Wars that is geared toward reinforcing the mechanisms of global capital. Orpana draws on ideas from Louis Althusser (Ideological State Apparatuses and intepellation) and Giorgio Agamben (Biopolitical Cultural Apparatuses) to explore the linkages to this ideology in the earlier Star Wars films, The Force Awakens, and Rogue One.

Considering how The Force Awakens changes the focus from the heroes of Anakin Skywalker and his son Luke to the heroine Rey, Payal Doctor explores how Rey’s heroine path differs from those of Anakin and Luke, and what these differences might mean in our understanding of Rey in a contemporary context. Her essay, “The Force Awakens: The Individualistic and Contemporary Heroine,” leverages Joseph Campbell to uncover how Rey escapes the traditional hero myth to respond to the political moment of the here-and-now.

Finally, the editors were honored to interview Cass R. Sunstein, the distinguished legal scholar and author of The World According to Star Wars. In this book, Sunstein explores what Star Wars has to teach us about our world, which is the primary lesson of any science fiction text—to tell us about the here-and-now. In our interview with Professor Sunstein, we endeavor to go beyond the text, discover what was left out, and what his thoughts are on The Force Awakens.

We hope that readers will enjoy these multimodal critical responses to the transmedia phenomenon of The Force Awakens. Even more so, we hope that readers will engage our writers’ ideas in regard to these transmedia components of the on-going Star Wars story and beyond.

Editors’ acknowledgements: The editors would like to thank Alan Lovegreen for his early help in making this issue possible, especially during our animated conference calls. NANO’s editorial board and other scholars were active in helping the process, and we would especially like to call attention to the following: Tom Burke, Mark Bruce, Rebecca Devers, Hugh Ferrer, Yufang Lin, Tara Robbins Fee, Paul King, Lucas Kwong, Robert Leston, John Loughlin, Lara Saguisag, Danny Sexton, and Angela Warfield.

Works Cited

Grossman, Lev. “A New New Hope: How J.J. Abrams Brought Back Star Wars Using Puppets, Greebles, and Yak Hair.” Time, 14 Dec. 2015, pp. 56-75.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York UP, 2006.

---. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. Routledge, 1992.

Kamp, David. “Star Wars: The Last Jedi, the Definitive Preview.” Vanity Fair, 24 May, 2017, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/05/star-wars-the-last-jedi-cover-portfolio. Accessed 16 Dec. 2017.

Krämer, Peter. “‘It’s aimed at kids—the kid in everybody:’ George Lucas, Star Wars and Children’s Entertainment.” Scope: An Online Journal of Film Studies, Dec. 2001, http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/scope/documents/2001/december-2001/kramer.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov. 2017.

May, Jill P. “Mass Marketing and the Toys Children Like.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 1, Spring 1982, pp. 5-7.

Pennington, Ron. “Star Wars: THR’s 1977 Review.” The Hollywood Reporter, 25 May 1977, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/star-wars-review-1977-movie-752620. Accessed 17 Sept. 2017.

Sansweet, Steve. “I’m really confused about canon. Is Star Wars Gamer canon? What about the Marvel series? Are they now considered ‘Infinities?’” StarWars.com, 17 Aug. 2001, http://web.archive.org/web/20011006064339/http:/www.starwars.com/community/askjc/steve/askjc20010817.html. Accessed 16 Dec. 2017.

Schuker, Lauren A.E. “Voldemort Hath No Fury Like Angry Harry Potter Fans.” The Wall Street Journal, 8 Sept. 2008, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB122083361232508617. Accessed 19 Dec. 2017.

Shepherd, Jack. “Harry Potter Prequel About Voldemort Approved by Warner Bros.” Independent, 1 June 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/harry-potter-fan-film-warner-bros-voldemort-origins-of-the-heir-a7766346.html. Accessed 21 Dec. 2017.

“The Viacom Crackdowns.” fanlore.org, 14 Nov. 2017, https://fanlore.org/wiki/The_Viacom_Crackdowns. Accessed 16 Dec. 2017.

Woloski, Richard. “The Star Wars Saga US Release and Re-Release History.” StarWars.com, 21 July 2015, http://www.starwars.com/news/the-star-wars-saga-us-release-and-re-release-history. Accessed 16 Dec. 2017.

Contact:

Contact: