Welcoming the Dark Side?: Exploring Whitelash and Actual Space Nazis in TFA Fanfiction

by Cait Coker and Karen Viars

Published December 2017

Abstract:

From the release of its first trailer, Star Wars: The Force Awakens received a racist backlash in response to the character of Finn, a black Stormtrooper turned hero. Nonetheless, after the film’s debut, slash fans across the Internet joined to make the Finn/Poe and Finn/Poe/Rey relationships (known as ‘ships) among the most popular in both art and fiction, in what seemed to be a welcome sign of fandom’s evolution from the usual orgy of white cis-bodies. However, by the time TFA was available for legal download, the Kylo/Hux ‘ship had overtaken the others significantly, despite their lack of screentime and actual lines, and the fact that they were “actual space Nazis” and “evil space boyfriends.” This essay will explore the intersections of racism and misogyny in TFA fanfictio, discuss why these most problematic ‘ships have become the most popular, and consider how the mainstreaming of the Empire in the popular imagination is a form of political whitelash.

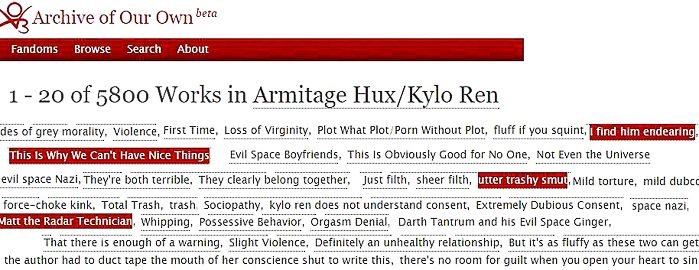

From the release of its first trailer, Star Wars: The Force Awakens (TFA) received a racist backlash in response to the character of Finn, a black Stormtrooper turned hero. Angry promises to boycott the film emerged alongside racist rants from “fans” and non-fans alike. Nonetheless, after the film’s debut a year later, slash fans (who read same-sex friendships onscreen as straightforwardly romantic) across the Internet joined to make the Finn/Poe and Finn/Poe/Rey ‘ships (short for “relationships” in fan fiction) among the most popular in both art and fiction. This seemed to be a welcome sign of fandom’s evolution from the usual orgy of white male cis-bodies which Mel Stanfill (2011) has analyzed at length. However, by the time TFA was available for legal download, the Kylo/Hux ‘ship had significantly overtaken the others in popularity—despite their lack of screentime and lines, and the fact that they were actual space Nazis. Fans were thus knowingly writing romances about genocidal fascists. The ‘ship remains the most numerous pairing in the fandom on the massive Archive of Our Own (AO3) site; at the time of this writing, Kylo/Hux stories number 10,773 to Finn/Poe’s 7,468, Kylo/Rey’s 6,340, and Finn/Rey’s 1,045. The heroes of the film—Finn, Rey, and Poe, all portrayed by minorities—are therefore displaced in favor of the white villains in fan culture, both in fan-created fan works and in licensed material created for consumption by fans. As Amy Sturgis observes in her discussion of Star Wars and indigenous peoples for the Unmistakably Star Wars podcast, the representation of minority and indigenous peoples in the films echoes that of the real world in fascinating ways; “We are the Empire,” she states, arguing that the conflicts in the Star Wars films present numerous opportunities for self-critique in how characters are portrayed from various cultures and stages of colonial identity. That a majority of fandom appears to be more interested in adopting the accoutrements and characters of the oppressors rather than the rebel heroes speaks to a broader problem in our culture.

While fannish interest in redeeming and rewriting villains is not new, the impulse to valorize fascist white villains at the expense of diverse heroes remains a symptom of the troubling, broader problem of popular whitelash and the alt-right in American culture. “Whitelash” as a term was coined by CNN commentator Van Jones in response to the election of Donald Trump to the American presidency; it “describes an old reality: Dramatic racial progress in America is inevitably followed by a white backlash” (Blake par. 1). In similar fashion, fannish response to TFA has pushed back against the progressivism of the text to reiterate the “traditional” values of white male bodies for a white female audience, creating a fannish corollary to the nationalist impulses of global politics in the real world. Sarah N. Gatson and Robin Reid described in their editorial for a special 2012 issue on “Race and Ethnicity in Fandom” for Transformative Works and Cultures some of the anti-racist work and debates that have taken place in fandom, but observing that in Fan Studies, despite decades of work, “the scholarship on fandom has an immense gap when it comes to dealing with race” (par. 4.12). Five years later, parts of fandom are still inadvertently, if not purposely, engaging in pro-racist behaviors, and there remains a dearth of academic work to engage with these problems. The rise of the “alt-right” is part of whitelash, and it cannot be dismissed in the reception of popular culture media like TFA.

Liam Stack, writing for the New York Times defines “alt-right” as “a racist far-right movement based on an ideology of white nationalism and anti-Semitism.” Stack notes that the alt-right movement “is anti-immigrant, anti-feminist and opposed to homosexuality and gay and transgender rights,” noting also that is “highly decentralized but has a wide online presence, where its ideology is spread via racist or sexist memes with a satirical edge” (par. 7). Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), are a group that, according to James S. Fell, “believe passionately in their own victimhood and their creed goes something like this: Women are trying to keep us down, usurp all our power, taking away what it means to be a man” (emphasis original) (par. 4). These groups share some overlap in ideologies and goals, all of which are toxic to women and minorities. Privileging white villains over female and non-white male characters exemplifies one of the many ways that whitelash and misogyny manifest.

This essay will make use of the burgeoning field of Fan Studies and theory to explicate specific practices in TFA fandom. In most discussions of fan writing and fan works, there is an impulse to declare fan spaces as utopic; examining the early Star Trek fan works in her 1997 book NASA/TREK: Popular Science and Sex in America, Constance Penley writes that fannish discourse and fiction created a “language to describe and explain the world and to express yearnings for a different and better condition; it is, then a common language for utopia” (16). In addition to the popular conceit of fans as disempowered Davids to intellectual and corporate property rights’ Goliaths, fandom is both perceived and promoted as queer-friendly and a creative, non-judgmental safe space. However, fans in fan spaces remain subject to the same systemic oppressions as all other spaces. In Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction (2016), André M. Carrington writes that despite “a generation of cultural criticism published about the ways in which popular texts resonate with the interests of attentive, actively engaged fans and academic researchers concerned with gender, sexuality, class, national identities, and changing technologies” there has been little interest in or progress made in discussing the topics of race and racism in SFF culture and fandom (1). Indeed, fan space has become a battleground for identity politics in recent years, from 2009’s encompassing Racefail imbroglio to 2014’s Gamergate to the ongoing debates in the Hugo Awards communities regarding “social justice warriors” While members of TFA fandom did not intend to become part of this broader historical trend, they definitely contributed to it, as did, perhaps surprisingly, the franchise itself.

Mainstreaming Scum and Villainy

Given that fandom spaces exist within larger sociocultural contexts, it is important to note official TFA merchandising’s heavy focus on the Nazi-derived stormtroopers and their fascist leader Kylo Ren to appeal to fans. This is not a new approach for the Star Wars franchise, which, while it has provided toy X-wings and Yoda backpacks aplenty, has always prominently featured the villains, particularly Darth Vader. Darth Vader remains as large a figure on the Star Wars merchandising landscape as he has ever been; however, TFA’s new heroes have been displaced by Kylo Ren. Unlike Darth Vader, whose narrative arc is redemptive and shown over multiple films, Kylo Ren is the Dark Side personified: violence and oppression founded on fear, anger, and hate. His image is everywhere, functionally glorifying and normalizing the values he represents in the film, and this despite the fact that he is only present in the film for less than twenty minutes. Stormtroopers, whose appearance in Star Wars merchandise (merch) was ancillary before TFA, have also proliferated. This change in merchandising—villains and Stormtroopers rather than heroes—could have been positioned to promote Finn, a former stormtrooper, as a main character of the film. Merch that presents Kylo Ren as a viable anti-hero with stormtroopers in full uniform instead causes those stormtroopers to appear as anonymous henchmen supporting the First Order’s regime, which Finn, who deserted to avoid killing innocents, clearly did not. While Finn merch, though problematic, was at least available for sale, merch featuring the film’s other protagonist, Rey, was not.

Darlena Cunha, writing for Time less than a month after TFA’s theatrical release, noted the almost-immediate fan response to the dearth of Rey-focused merch: “[J]ust 20 days after [TFA’s] release, fans were clamoring to stores online and off, looking for merchandise representing their favorite characters. And many have wondered: where’s Rey?” She goes on to note:

We still seem to live in a corporate world that thinks girls don’t play with action figures, and that female leads aren’t as interesting as male leads. But now this outmoded thinking is costing not only society, but also company bankrolls. Stores have seen Rey merchandise fly off the shelves. They can’t stock it as fast as the fans want it. And it’s not just for the girls. Boys want the toys, too. (Cunha par. 4)

Monica Tan, also writing in early January 2016, reported on Hasbro’s omission of Rey as a character token in its TFA edition of the game Monopoly. The four characters selected for game tokens were Finn, Kylo Ren, Luke Skywalker, and Darth Vader. Rey has more screen time and a larger role in the film than all these male characters. It is telling that Hasbro chose to include Darth Vader, a character who does not appear in TFA except for his iconic yet deformed helmet, rather than Rey, whose story the viewer follows throughout the film. Tan reports,

A trending hashtag, #WheresRey, has been charting the absence of Rey from chain store shelves selling the film’s official merchandise. Similar complaints have been made about the difficulties of finding other female action hero figurines, including Scarlett Johansson’s Black Widow from the Avengers movies and Zoe Saldana’s Gamora from Guardians of the Galaxy. (par. 8)

The #wheresrey hashtag, which was widely used on social media, was created to question Rey’s absence in Star Wars merch, and serves as evidence of the backlash against minority characters, including women, occupying the spaces that are often the domain of white male characters such as Kylo Ren or Armitage Hux. The hashtag also asks about a larger absence: valuing women’s visibility in leading roles.

TFA villains take the spotlight beyond the franchise as well: Adam Driver, the actor who plays Kylo Ren, hosted Saturday Night Live on January 16, 2016, at the same time that news articles were documenting the #wheresrey hashtag. One of the comedy skits in which Driver appeared was in fictional episode of the Undercover Boss television show, where Kylo Ren pretends to be a radar technician named Matt in order to get to know more about the day-to-day operations of Starkiller Base. After an interview with Kylo Ren about his agenda to “restore the galaxy to its rightful state,” the viewer sees him interacting with Imperial officers and stormtroopers, who reinforce this vision of “rul[ing] everything.” While there are humorous gags centered on Kylo Ren’s uncontrolled temper, responsibility for the death of an officer’s son, and inability to work well with others, ultimately this skit contributes to the normalization of Kylo Ren and the Imperial forces and the goals they pursue—he becomes a socially awkward “boss” for the amusement of the audience, an audience that then sees events from his perspective. If, instead, this opportunity had been used to follow Finn’s experience as a disillusioned stormtrooper, it could have underscored the costs of a charismatic and angry leader’s vision both to individuals and the larger culture. Instead, providing Kylo Ren with a platform that makes his violence humorous puts him, rather than the minority heroes, at the center of the narrative and normalizes his unconscionable choices, another form of whitelash.

The mainstreaming of Kylo Ren and the stormtroopers, privileging their appearance in merchandise over a woman and characters of color who had larger roles in the film, occurs against a backdrop of high anxiety in contemporary American culture. A look back over the last twenty years provides chaotic context, particularly for Millennial viewers of TFA. A fan from the US born in 1995 was five or six years old the World Trade Center towers fell on 9/11, followed quickly by a war that would last most of her childhood, which she spent in an educational system that demanded high performance on standardized tests. The 2008 global financial crisis occurred as she entered high school, making access to a college degree harder to afford while steadily decreasing housing security. And if she was able to obtain a college degree, she still faces worse economic prospects than did previous generations. The Pew Research Center reported in 2014 that

[Millennials] are entering adulthood with record levels of student debt: Two-thirds of recent bachelor’s degree recipients have outstanding student loans, with an average debt of about $27,000. Two decades ago, only half of recent graduates had college debt, and the average was $15,000. (Pew Research Center)

It is perhaps inevitable, then, that “[M]illennials are more stressed than any other current living generation” (Castillo). Given these facts, even a fan whose personal beliefs are not overtly or intentionally racist or misogynist could identify with Kylo Ren, who spends his brief onscreen moments exercising power to seek explanation and redress for a world that has, in his view, deviated from its logical and ideal course. And for fans who are part of the alt-right or MRAs, identifying with the villains becomes even easier. Anxiety from coming of age in the modern world, coupled with the presentation of Hux, Kylo Ren and stormtroopers as culturally normal, results in a greater interest in and fannish creative focus on these characters, aligning fans and the TFA fandom with deeply problematic political and cultural ideologies.

Confronting the “Dark Side” of Fandom

As mentioned above, fandom is less of an idyllic space than many narratives would have us believe, and just as easily prey to systemic oppressions—especially with regards to race and other -isms. However, fandom tends to carry certain assumptions about fans that become narrative defaults; these include the supposition of youth, queerness, and whiteness that are not necessarily true in general and not at all true in various specific fandoms. The narrative defaults also act as a form of erasure. Sarah N. Gatson and Robin Reid clarified this issue in their Editorial to a special issue of Transformative Works and Cultures on the topic:

Not to speak about race, gender, class, sexuality—or being pressured not to speak—in a fandom space ends up creating the image of a “generic” or “normalized” fan. Such a fan identity is not free of race, class, gender, or sexuality but rather is assumed to be the default. The default fanboy has a presumed race, class, and sexuality: white, middle-class, male, heterosexual (with perhaps an overlay or geek or nerd identity, identities that are simultaneously embedded in emphasized whiteness, and increasingly certain kinds of class privilege, often displayed by access to higher education, particularly in scientific and technical fields). We're being disingenuous if we pretend that these social forces do not exist and do not affect fandom interactions, with different effects in off-line and online fandom spaces. (4.1)

Confronting the dark side of fandom begins with the acknowledgement of real world social forces and, hopefully, ends with insights into how and why fans and fandom recreate these issues in fan spaces. This also holds true for the discipline of Fan Studies itself. Rebecca Wanzo uses African American Studies as a model for reconfiguring Fan Studies to take these intellectual gaps into account, writing that “One of the reasons race may be neglected is because it troubles some of the claims—and desires—at the heart of fan studies scholars and their scholarship” (1.4). Fans and acafans (or academic fans) want to see the good at the heart of fandom and tool their narratives accordingly, but this only shows part of the story: fandom must also be investigated as a troubling and dark space.

The scholarship on problematic aspects of fandom is rather sparse. Robin Anne Reid has written on the use of darkfic in slash in her 2009 essay “Thrusts in the Dark: Slashers’ Queer Practices” where she usefully classifies the genre as “tragedy minus catharsis” (467). However, to date there have been no formal studies on long-running trends in fandom such as noncon (fan fiction that contains non-consensual sex, which the story may or may not portray as rape), dubcon (fan fiction that contains sexual scenes with “dubious consent” where there may not be a formal assent but at least one character is uncertain about whether they want to be a participant), and more recently, “trash memes” where anonymous fans can request or provide fic and art that they acknowledge to be problematic, including rapefic. The gap in scholarly interest in these areas is reflective of the usual emphasis on fandom as a safe space per Constance Penley and other media scholars who make up a traditional narrative that “emphasizes women’s inclusion and creative control” (148) in revising pop culture texts in fan writing, and seemingly, a reluctance on the part of researchers to disclose interest on these topics. (A useful contrast in scholarship can be found in Romance Studies, which has, to date, numerous studies on the topics of rape and romanticizing problematic sexual narratives. See: Critelli and Bivona, 2008; Bivona and Critella, 2009; Toscano, 2012.) As Rukmini Pande has recently pointed out, the “mainly heterosexual, cisgender, white, middle class American women” (209) fans have historically skewed academic investigations into fandom, presenting a utopic vision at odds with the troubling spaces that they often are in real life.

A final trend sees prominent black characters and other people of color being minimized or erased in fan works. In her essay on anti-black racism, Dominique D. Johnson writes that, “Representationally, we see POC [People of Color] as stock, archetypal figures whose primary purpose is to either forward the story arcs of white protagonists or as comic relief. This sidelining of POC stories and perspectives can be reflected in SF community practices that emerge as suppressive, oppressive politics” (266). A notable example of this activity is in the Marvel Cinematic Universe fandom, as when Sam Wilson/Falcon is deleted in fanvid edits so that Tony Stark/Iron Man appears at Captain America’s side instead, or when T’Challa/Black Panther is reduced from a king and a warrior to providing equipment and safe haven to the Avengers. And of course, in TFA fandom, when Finn, who is the main character, is replaced by Ben Solo/Kylo Ren as the love interest for Rey and the hero of the story. While the romanticization and woobification (best described as a fannish impulse to comfort and sympathize with a particular character) of villains is by no means new, in TFA fandom these urges become profoundly problematic because they are aimed at “space Nazis.” The term both acknowledges the real world influences on the characters (Lucas, Abrams, and their designers consciously drew on Nazi imagery in costume design and dialogue rhetoric) and the fictional world in which these politics are enacted. These are characters who have committed genocide by destroying entire planets, professed authoritarian/totalitarian beliefs, persecuted our heroes (who are also minorities in the real world by virtue of being POC and/or women), and in the specific case of Kylo Ren, also committed patricide. Highlighting them as heroes whileminimizing the roles of minority characters is evidence of the whitelash response.

Fannish perception of Kylo Ren is perhaps best demonstrated by his bifurcated tag on AO3 (Archive of Our Own, the massive fan work archive housed by the Organization for Transformative Works), “Ben Solo | Kylo Ren.” AO3 tags are used to find and sort fan works easily for the searcher, with a particular focus on character names and on slashed character names to indicate romantic relationships (from the famous “Kirk | Spock”). This bifurcation is unusual for the site specifically and fandom in general. For example, it is not used in Avengers or DC fandom despite those franchises’ characters who have dual identities as super heroes/villains, such as Steve Rogers as Captain America or Bruce Wayne as Batman. In those fandoms the emphasizing tag is on their “real name” rather than on their secret identities, even if the secret identities are the main focus of the story. The bifurcation is however present in Star Trek Reboot fandom with the character John Harrison who is ultimately revealed in the film to be Khan Noonien Singh. However, the plot twist to reveal Harrison as Khan was not well-received by fandom (to put it mildly); many stories choose to overlook it altogether. Therefore the tag “John Harrison | Khan Noonien Singh” indicates the use of a specific character’s representation in the canon rather than the use of the character per se.

By adopting this mode in TFA fandom, use of the tag “Ben Solo | Kylo Ren” implies at once a discomfort with the use of that character in the canon, the author’s signalled intent to revise that character for the fan work (eg, more “Ben Solo” and less “Kylo Ren”), and manipulation of the tag system such that all stories with “Kylo Ren” now have an influx of “Ben Solo” characterizations and plots. (This tag manipulation within the system is well-known for corrupting searches for specific ‘ships. Primary and secondary ‘ships in fics are not separated within this system, so for instance a search for “Finn | Poe” stories will include all stories with that tag, even those where the Finn/Poe is a barely-there background ‘ship and the story focus is on Rey/Kylo Ren or Hux/Kylo Ren. Further, Hux/Kylo Ren has two tags for the ‘ship which are used interchangeably; “Hux | Kylo Ren” and “Armitage Hux | Kylo Ren.” This interchangeability is fairly unusual in fan tags; more often there is one accepted usage and one or two other usages that came about before the widespread adoption of the main tag.) Tag manipulation has the side effect of skewing results and normalizing parts of fandom until they are functionally accepted and even become “fanon” (or fan canon). This can be most clearly seen in the dramatic rise of Kylo Ren in fandom generally and of Hux/Kylo Ren (also known as Kylux) fandom in particular. In May 2016, a month after TFA was available for legal download and purchase on DVD, Kylux was already the most popular pairing in the fandom with over two thousand stories; as of September 2017, the numbers are closing in to over ten thousand stories devoted to fandom’s beloved “Evil Boyfriends.”

Rescuing Ben Solo?

In April 2016, the fandom statistics blog Destination: Toast! provided a lengthy statistical analysis of TFA fandom that extensively documented the shifts in the fandom on AO3, especially the shrinking popularity of Finn/Poe and the growing popularity of Kylux. Fans took notice of this post, and proceeded to analyze it at length. When asked about the topic of race in terms of ‘ships’ popularity, Destination: Toast! added a second addendum to the post to address the question directly:

Another factor many people have brought up: race. It seems very likely that is an influencing factor here–how could it not be, given that society at large (and fandom as a part of it) certainly have a LOT issues around race, and in aggregate, POC ships are much less common across most fandoms. However, I don’t think that’s the whole story, either–it’s interesting that Finn/Poe had a meteoric rise at the start (when so many ships featuring POC never get popular at all), and followed by a steeper decline than I’ve often seen. And it’s also interesting that (white) Rey also saw an early peak, at least on AO3. So it’s not a super simple story there of how race caused this, even though it’s a likely contributing factor. (Destination: Toast!)

Other commenters were blunt in their response as to the likely cause for the shift in popularity, such as Tumblr user Diversehighfantasy:

But if Ren is going to be the good guy, the sympathetic hero, in fanfic, why not Finn? This, to me, is where every non-racial claim falls apart. Ren ships are the most popular because he’s considered the most attractive. Hux is considered attractive. White is considered attractive, sexual, worthy of attention no matter how small the part. This is the absolute bottom line, everything else is just noise. (emphasis original)

After an extensive online conversation, Diversehighfantasy was more emphatic still:

I am comfortable saying Kylux is a racist ship, but not because I think each and every Kylux fan is a card carrying KKK-style racist. I’m sure it’s true that some bailed on Stormpilot because of the racism and turned to Kylux because they’re into dark and dirty slash. But that’s not really the point. If 10% of the TFA fics on AO3 were Kylux, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. It is by far the most popular ship, and this is a pattern in fandom.

Indeed, this pattern can be seen over and over again across multiple fandoms, valorizing and fetishizing white male bodies at the expense of all others (see Stanfill). Denying that the problem is race is wishful thinking: Kylux and TFA fandom have demonstrated that fandom itself does not exist independently from larger sociocultural problems.

Ben Solo, as a character distinct from Kylo Ren, creates a loophole for a redemption story. As discussed previously, redeeming a problematic character is familiar fannish practice; however, unlike many other characters whom fandom adopts for this purpose, Ben Solo is a blank slate. The viewer knows only that he is Han Solo and Leia Organa’s son, and that his parents miss and fear for him. While never directly stated, it is implied that Ben Solo was a student of Luke Skywalker, who turned to the Dark Side. We know nothing of Ben Solo, except his family relationships, making him a character ideally positioned to accept any traits that fans wish to project. To an author keen to fix the problems that Kylo Ren’s murderous actions and philosophies present, the lack of canon about Ben Solo’s character is a boon; his singular tag currently encompasses some 1,800 works. Ben Solo can eschew responsibility for his alter ego’s violent, hated-driven actions, and become one of the “good guys,” though at significant cost to other characters.

However, Ben Solo is still Kylo Ren. In TFA canon, Kylo Ren violates Rey’s mind in his quest to find BB-8 and information that may lead to Luke Skywalker; he leaves her shaken from a mentally invasive interrogation and in physical restraints. Absolving Ben Solo of Kylo Ren’s actions, then, happens at Rey’s expense: she can forgive Kylo/Ben for his invasion of her self, or she can “save” him through her own innate goodness. Both options focus on his narrative arc. Rey’s needs as a trauma survivor, orphan, new member of the Rebel Alliance, Jedi-in-training, and other critical aspects of her character are sidelined in service of rescuing him from his choices. Kylo Ren’s idol and grandfather, Darth Vader, earned redemption, as a literally broken man acknowledging and attempting to atone for his mistakes. Kylo Ren has, thus far, made no such efforts. While he may yet determine the Dark Side’s price is too high to pay, at the conclusion of TFA, he commits to it deeply enough to murder his father, a fact that the redemption stories of Ben Solo often choose to excuse or ignore. By “rescuing” Ben Solo, fans remove Kylo Ren from the responsibility of his choices and normalize his fascistic tendencies—yet another provocative whitelash back at the minority heroes.

Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Conclusions

Surveying the wide array of fan works that focus on Kylo Ren/Ben Solo and Hux reveal fandom’s impulse to rescue minor characters in what Deborah Kaplan has called the “constant conversation” between “the simplistic interpretation of the source text...and the more complex interpretations spoken for in fan fiction” (150), and, in this case, see the anti-hero within every villain. While this impulse has traditionally been lauded, we view it as a problematic aspect of contemporary popular culture that normalizes politics that, frankly, should be problematic. While the nomenclature of “Actual Space Nazis” is used in jest, it is nonetheless accurate in describing these characters. The attention fandom and popular culture lavish on them could be focused on Poe Dameron, Finn, and Rey, the true heroes of the film whose stories are treated as trivial in comparison. These three characters are the impetus for the plot, the heart of the narrative, and the continuation of the story that began with A New Hope. Further, Finn is a stormtrooper who chooses to redeem himself over the course of the film, justifying the very tropes that fans want to explore, and yet he is not considered essential to the fan work in many pieces of writing. That Poe, Finn and Rey are characters of color and a woman cannot be ignored in a culture that privileges whiteness and masculinity and the structural power inherent in these traits.

From its inception in the early 1990s, Fan Studies has celebrated fandom for creating a safe and progressive space for fan writers. From the pioneering work of Henry Jenkins, who concluded in Textual Poachers that “there is something empowering about what fans do” in transmuting popular texts into fan works (284), to Francesca Coppa’s anthology The Fanfiction Reader: Folktales for the Digital Age that is presented as “a labor of love” for the reader (16), fandom is presented as utopic space for participants. Yet over and over again we see how this is far from true, despite the field’s reluctance to explore this aspect. American fandom in particular sits at a political crossroads in which real world issues intersect with fan works. The “Dark Side” of TFA fandom has demonstrated a tendency towards a whitelash at odds with the progressivism of the source material, a political situation that is, if not unique, certainly indicative of greater problems inside and outside of fan culture. While previous work has expanded on the problematic treatment of black characters—perhaps best exemplified by the “Uhura wars” of Star Trek reboot fandom—never before have the main heroes of a pop culture franchise been men of color who have been systematically erased in the fan work as Finn and Poe have been. While celebrating minority heroes is the norm, when the minority becomes white men who are the true epitomes of toxic masculinity, we have a cultural problem that must be queried and closely examined to uncover the politics of fandom. As the past two years have seen political activism and dissonance merge with popular culture, it is now more important than ever to acknowledge, and remedy, fandom’s dark side.

Works Cited

Archive of Our Own. The Organization for Transformative Works. http://archiveofourown.org/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Bivona, Jenny, and Joseph Critelli. “The Nature Of Women's Rape Fantasies: An Analysis Of Prevalence, Frequency, And Contents.” Journal of Sex Research, vol. 46, no. 1, 2009, pp. 33-45.

Blake, John. “This is what ‘whitelash’ looks like.” CNN.com, 19 Nov. 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/11/11/us/obama-trump-white-backlash. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Carrington, André M. Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction. U of Minnesota P, 2016.

Castillo, Michelle. “Millennials are the most stressed generation, survey finds.” CBS News, 11 Feb. 2013, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/millennials-are-the-most-stressed-generation-survey-finds/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Coppa, Francesca, Ed. The Fanfiction Reader: Folktales for the Digital Age. U of Michigan P, 2017.

Critelli, Joseph W., and Jenny M. Bivona. “Women's Erotic Rape Fantasies: An Evaluation of Theory and Research.” Journal of Sex Research, vol. 45, no. 1, 2008, pp. 57-70.

Cunha, Darlena. “‘Where’s Rey’ Proves Kids Are Light Years Ahead of Toy Companies.” Time.com, January 7, 2016, http://time.com/4170424/star-wars-wheres-rey/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Destination: Toast! A Fandom Statistics Blog. “So what’s been going on in the Star Wars fandom lately? (probably not much, right?)” 24 Apr. 2016, http://destinationtoast.tumblr.com/post/143364198849/bigger-bigger-bigger-bigger-toastystats. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Fell, James S. “The Toxic Appeal of the Men’s Rights Movement.” Time.com, 29 May 2014, http://time.com/134152/the-toxic-appeal-of-the-mens-rights-movement/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Full-Color Fantasy (Diversehighfantasy). “So what’s been going on in the Star Wars fandom lately? (probably not much, right?)” Tumblr. 28 Apr. 2016, https://diversehighfantasy.tumblr.com/post/143564238106/thebb-k8-jawnbaeyega-diversehighfantasy. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Gatson, Sarah N. and Robin Reid. “Editorial: Race and Ethnicity in Fandom.” Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 8, 2012, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/392/252. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. Routledge, 1992.

Johnson, Dominique D. “Misogynoir and Antiblack Racism: What the Walking Dead Teaches Us About the Limits of Speculative Fiction Fandom.” Journal of Fandom Studies, vol. 3, 2015, pp. 259–275.

Kaplan, Deborah. “Construction of Fan Fiction Character Through Narrative.” Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet, edited by Karen Hellekson and Kristina Busse, McFarland, 2006, pp. 134-152.

Pande, Rukmini. “Squee From The Margins: Racial/Cultural/Ethnic Identity in Global Media Fandom.” Seeing Fans, edited by Paul Booth and L. Bennett, Bloomsbury, 2016, pp. 209-220.

Penley, Constance. NASA/TREK: Popular Science and Sex in America. Verso, 1997.

Pew Research Center. “Millennials in Adulthood.” Pew Research Center. 7 Mar. 2014, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/03/07/millennials-in-adulthood/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Reid, Robin Anne. “Thrusts in the Dark: Slashers’ Queer Practices.” Extrapolation, vol. 50, no. 3, 2009, pp. 463-483.

Stack, Liam. “Alt-Right, Alt-Left, Antifa: A Glossary of Extremist Language.” The New York Times, 15 Aug. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/us/politics/alt-left-alt-right-glossary.html. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Stanfill, Mel. “Doing Fandom, (Mis)doing Whiteness: Heteronormativity, Racialization, and the Discursive Construction of Fandom.” Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 8, 2011, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/256/243. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Tan, Monica. “Hasbro to release Star Wars Monopoly with Rey after #WheresRey campaign.” TheGuardian.com. 6 Jan. 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jan/07/hasbro-to-release-star-wars-monopoly-with-rey-after-wheresrey-campaign. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Toscano, Angela R. “A Parody of Love: The Narrative Uses of Rape in Popular Romance.” Journal of Popular Romance Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 2012, http://jprstudies.org/2012/04/a-parody-of-love-the-narrative-uses-of-rape-in-popular-romance-by-angela-toscano/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

Wanzo, Rebecca. “African American Acafandom and Other Strangers: New Genealogies of Fan Studies.” Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 20, 2015, http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/699/538. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

“What Indigenous Peoples in Star Wars Can Tell Us About Our Real World, Featuring Dr. Amy Sturgis, PhD.” Unmistakably Star Wars from the Star Wars Escape Pods Network, 8 November 2017, http://www.unmistakablystarwars.com/ep107/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.