Editor’s Introduction for NANO Special Issue 14: Captivity Narratives Then and Now: Gender, Race, and the Captive in Twentieth- and Twenty-First-Century American Literature and Culture

by Megan Behrent

Published September 2019

In 2018, forty-five years after the high-profile abduction of Patricia Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army, CNN returned her captivity narrative to mass media in the documentary series The Radical Story of Patty Hearst. A year later, Netflix brought to a close the narrative of Kimmy Schmidt, the ever optimistic and resilient survivor of childhood abduction and fifteen years of captivity in a bunker. Tales of captivity have dominated the digital streaming universe in recent years even as the captivity narrative has proven to be a malleable genre: from the dark dystopia of The Handmaid’s Tale which powerfully depicts the horrors of survival in a world in which women are reproductive slaves, to WestWorld, set in a virtual game park recreation of captivity narratives past, a bleak commentary on the fascination narratives of the American western hold for eager guests who are unaware of the rebellion brewing among captive hosts, to the 1980s world of Stranger Things, whose first season focuses on the tale of two abducted children, and Orange is the New Black a show devoted to America’s largest captive population, the mass incarcerated, and in its last season, the detainees of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). This special issue of NANO is devoted to examining the cultural significance of contemporary captivity narratives and the ways they both defy and reify the cultural and political logic of early American narratives that originated the genre.

A recent article in The Atlantic by staff writer Megan Garber examines contemporary invocations of the captivity genre and the fascination it holds for a captivated streaming public, arguing that the proliferation of the genre is “a latent response to” the “stranger danger” which reached its height in the 1980s during a formative period for many contemporary creators of the genre. The period was marked by a cultural anxiety created by sensationalized tales of abduction and abuse by day care providers, such as a 1990 Newsweek article on “the dark side of daycare” that prominent feminist scholar Susan Faludi emphasized in her influential 1991 bestseller Backlash: The Undeclared War on Women, which linked the popularity of this new genre of captivity narrative to a backlash against second-wave feminism and its quest to liberate women from imprisonment in the domestic space (57). It is thus not surprising that Stranger Things, one of the most popular of the recent crop of televised captivity narratives, is very consciously rooted in 1980s suburbia. While the 1980s provide one cultural reference point for the current proliferation of the captivity narrative, the era of #MeToo has ushered in a new form of mass story telling that evokes a certain kind of captivity whose hold is broken by the act of speaking out publicly and connecting one’s individual story to a collective movement of narrative creation. Echoes of this movement reverberate in contemporary captivity narratives in which the resilience of a newly self-empowered protagonist/survivor is highlighted. Garber sees contemporary rewritings of captivity narratives as “feminist fables…concerned with the woman actively rescuing herself.” Nonetheless, she notes, “they don’t necessarily represent a reversal of the Grimm story; rather, they complicate it for a time of upheaval and anxiety when it comes to women’s roles.” Early captivity narratives such as that of Mary Rowlandson, the first bestseller of the genre, likewise emphasized the resilience of the captive, even as her ability to survive was attributed to faith, piety, and divine intervention, reinforcing Puritan religious ideology. While the conventions of the genre have been adapted and reinvented amidst changing political contexts and material changes to the production and dissemination of narratives in popular media, it nonetheless remains rooted in what Faludi aptly termed in 2007 the “Terror Dream” to describe the ways in which the early fantasy and mythology of American national identity forged by captivity narratives were re-mobilized in the post-9/11 era.

In exploring tropes of captivity in contemporary popular media, this issue of NANO draws on existing scholarship to reflect on the particular resonance of the genre in the early part of the twenty-first century. Scholars of captivity narratives have highlighted its important place in American literary, cultural, and political history as the literary expression of the “imagined community” of the nation described by Benedict Anderson. In addition to the work of Nancy Armstrong (who is interviewed in this special issue of NANO), Rebecca Blevins Faery, Christopher Castiglia, Cathy Rex, Gordon Sayre, and Susan Scheckel have all contributed important insights into the foundational role of the genre. As many scholars have noted, and as contributors to this special issue reference, Mary Rowlandson’s ur-text played a foundational role in popularizing and establishing conventions of the captivity genre, including the use of a white female captive in constructing a national narrative of America under siege, even as its history and practice of international interventionism and protectionism challenge this narrative.

In The Terror Dream: Myth and Misogyny in an Insecure America, Faludi argues that post-9/11, the media was saturated with images of male heroism and virility, “perfect virgins of grief,” and security moms, while pundits heralded the opt out revolution that never was and promoted a new cult of motherhood and domesticity, all of which contributed to a resurgent political backlash against feminism. The vehemence of the anti-woman, anti-feminism rhetoric mobilized in the media, Faludi argues, was surpassed only by the simultaneous mobilization of feminism in the service of empire as military action was justified under the guise of liberating women in Afghanistan and Iraq. The centrality of the captivity genre to the promotion of this twenty-first century terror dream is underscored in Faludi’s treatment of the narrative of Jessica Lynch, a high-profile media story that captivated the American imagination, even as it turned out to be based on lies and distortions of actual events.

Like early narratives, the twentieth- and twenty-first-century captive is more often than not figured as white, threatened by a racialized other who invariably seems at odds with hegemonic ideas of American culture, freedom, and democracy even as scores of captives are kept in cages at the border, or in the carceral system in the name of that “freedom” and “democracy.” In the world of television, the popular and critically-acclaimed television show Orange is the New Black is notable for its centering of stories of women of color and gender non-conforming women—and yet, as many critics and the show’s creator herself has noted, this is made possible through the use of a white woman “Trojan Horse” (Jenji Kohan quoted in O’Sullivan 401). Piper Chapman, based on Piper Kiernan, the author of the memoir on which the show is loosely based, provides the viewer with an entry into the world of women captives. It is notable that a show devoted to the largest existing captive population in the United States, the mass incarcerated—a population in which people of color and the poor are disproportionately represented—deemed it necessary to begin with the privileged voice of an upper class white woman to sell its story to Netflix. Here too, the legacy of the captivity narratives of yore, is strongly imprinted on those of the twenty-first century.

While the experience of captivity animates the genre, to tell one’s story is only possible among those who survive the experience and are returned to some state of freedom—no matter how limited that might be—from which to tell their tale. The survivor’s story is nonetheless mediated by her frequent lack of editorial control over the narrative in a male-dominated world of publishing and popular media. Early Puritan writers such as Mary Rowlandson had to contend with the heavy-handed intervention by patriarchal church leaders in shaping the narrative’s publication and message. Contemporary memoirs of survivors of captivity are often mediated by ghost writers and a male-dominated entertainment industry in which the ability to sell the narrative is the bottom line. The question of who can tell their story is therefore not simply a question of authorship, but access to the means of producing modern media, and the marketability of the narrative—both of which reinforce hegemonic narrative norms and biases. One of the most compelling contributions of the #Metoo movement is its ability to break down the barriers to telling one’s story. Having gained mass attention in part because of Hollywood stars who helped popularize it, the Twitter activist phenomenon originated with Tarana Burke in 2006, and became a mass movement because of the millions of women who answered the call to tell their own stories (Burke). This included a powerful statement of solidarity by the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas who described the widespread sexual harassment and assault faced by farmworkers (“700,000 Female Farmworkers”). While the movement has yet to transform the production of contemporary captivity narratives, it has already had some impact on their production and reception. Whether contemporary social and political movements will continue to challenge the cultural logic of the seventeenth-century captivity narrative remains to be seen. The contributions of the scholars featured in this special issue of NANO provide an important lens to understand the cultural work of these narratives historically and in their current manifestation.

An interview with Nancy Armstrong opens this issue, providing an expansive cultural and historical analysis of the origins of the genre, its centrality to the development of an imagined national community, and to the development of a new ruling class. Armstrong explains the path her research took in pursuing these claims, from her work on British domestic fiction to American captivity narratives to the Barbary captivity narrative. Armstrong concludes by discussing the potential for reversals of the traditional roles of captor and captive in the current moment by turning her analytic lens to the #MeToo movement and international movements of migrants to discuss how the colonial and nationalist logic of the captivity narrative might be transformed in the current political period. Armstrong provides a trenchant analysis of the political significance of the captivity genre to early American settlers and their political heirs arguing that:

The captivity narrative transformed the British role into that of the righteous protector of womanhood (defensive violence) and bearer of domestic culture (aka civilization). This same redefinition of violence against a people as violence in defense of womanhood has been updated and reproduced through the centuries to legitimate the violence of a white (though certainly no longer British) ruling class over and against successive immigrant waves, as well as those marked as racially and culturally other.

Leslie Irvine and Wisam H. Alshaibi’s contribution to this issue of NANO, “Personal Trials and Social Fears: Examining Reflexivity in Captivity Narratives,” employs a sociological lens to demonstrate how “the reflexivity made possible through symbolic codes and abstraction” transform personal stories of captivity into “social problems” and have “influenced social change.” Irvine and Alshaibi focus on stories of child abductions such as that of Jaycee Lee Dugard and Elizabeth Smart that garnered immense popular attention in the media leading to book contracts and mass book sales. In exploring the “symbolic codes of trauma and childhood” in these narratives of captivity, Irvine & Alshaibi raise important questions about which stories receive media attention and the ways in which gender and race impact the construction of childhood.

In “Very Familiar Things: Captivity and Female Fierceness in Stranger Things,” Elena Furlanetto examines the growth of female-centered narratives and “the resurfacing of a frontier imaginary” in periods of crisis, particularly the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis. While Stranger Things is not a traditional captivity narrative, Furlanetto explores the show’s selective use of tropes that originate in seventeenth-century captivity narrative, most notably that of female fierceness and empowerment that lend themself to the “feminist fables” that Garber identifies, especially noting the iconic image of Mary Rowlandson holding a rifle, or the indelible image of Hannah Dustan fighting back, killing and scalping her captors. At the same time, Furlanetto demonstrates the show’s indebtedness to the exclusionary logic of early captivity narratives in constructing a community—the suburban Midwestern town of Hawkins, Indiana—uniting against a common enemy whose otherness and savagery is never questioned.

Charity Fox’s “Flashback to the Bunker: Reframing Echoes of Captivity in Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt” provides a timely analysis of the popular television which highlights Kimmy’s quest to control her own narrative. Fox shows how the narrative structure, particularly the use of flashbacks, challenges the conventions of the captivity narrative by withholding specifics about the abuse faced by the protagonist in captivity in favor of flashbacks that highlight her resilience. According to Fox, this narrative construction denies the audience the voyeurism which permeates other expressions of the genre. Fox highlights an important scene in the first episode in which the “Indiana Mole Women” are interviewed on the Today show by a condescending Matt Lauer, an experience which prompts Kimmy Schmidt’s initial decision to reject the victim narrative imposed upon her and take control of her own story. Lauer’s appearance on the show marks an uncanny moment of blurring between fact and fiction, airing two years before Lauer’s own predatory behavior was exposed, including allegations that he had held women captive in his office. This extra-textual narrative exposed by the #MeToo movement, along with countless stories of actors trapped in hotel rooms and studios in pursuit of work, imbues Lauer’s presence with new meaning, reminding us that there are a host of captivity narratives built into the production of contemporary fictional narratives of captivity that are so prevalent on twenty-first-century screens.

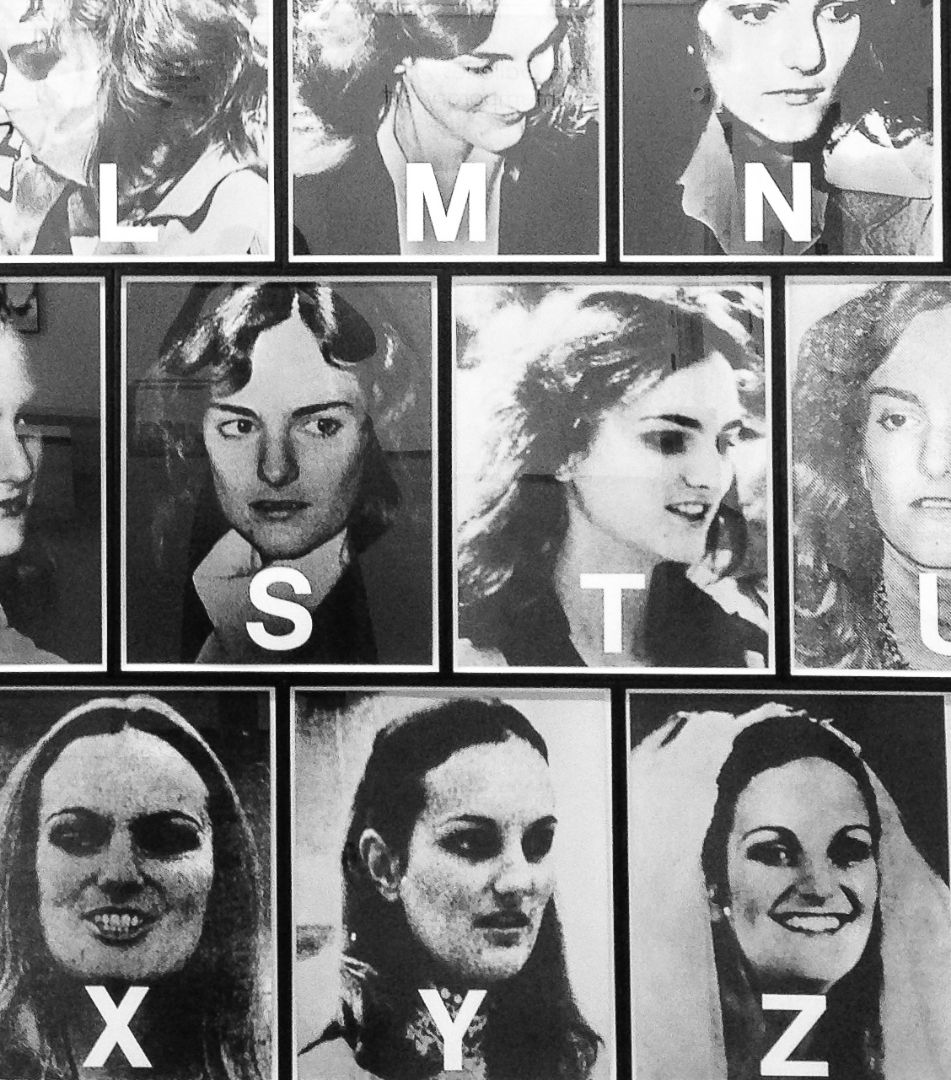

In “Narrative as Performance: American Heiress,” Visola Wurzer reviews Jeffrey Toobin’s 2016 American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes, and Trial of Patty Hearst, an in-depth history of the 1974 kidnapping of Patricia Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). Wurzer observes that Toobin’s structure reads like a five-act play, a narrative choice that she argues highlights the dramatics of the SLA. Wurzer also explores the repercussions of a narrative that fails to include the voice of the survivor herself. Hearst’s public comments on Toobin’s book and subsequent adaptations for the screen consciously evokes the #MeToo movement in critiquing Toobin for sensationalizing her own narrative of abduction, rape, and captivity and re-victimizing her by denying her voice and control over her own story. As Wurzer notes in discussing the impact of this changed context on the telling of one of the most infamous captivity narratives of the twentieth century, sellers are now offering deep discounts on Toobin’s book and plans for a film have been canceled.

As the articles in this special issue of NANO make clear, in its new forms, the twenty-first-century captivity narrative both perpetuates and contests the social construction of race, gender, and national identity endemic to early expressions of the genre. Despite challenges by the #Metoo movement, immigrant rights activists, and the authors and protagonists of captivity narratives themselves, tales of contemporary captives continue to reverberate with the long genre echoes of their seventeenth-century predecessors which contributed to the creation of an imagined national community based on exclusionary, oppressive, and even genocidal practices that reframed oppressors as an embattled community in need of defense from a racialized other. On America’s screens, it is often easier to imagine a captor who is comfortably other, whether the SLA or Stranger Things’ demogorgons than to challenge ICE ripping children from their parents at the border and placing them in cages. Nonetheless, Armstrong offers hope that there is potential to reverse the narrative logic of the genre and transform the figure of the captive. Despite attempts in 2019 by the Trump government and the far right to depict migrants as aggressors threatening the porous borders of an embattled nation, the current prevalence of “images of children in cages surrounded by US immigration officials,” Armstrong argues, “suggests that the captivity narrative is once again gathering together the historical materials at hand in order to resituate the question of national identity on an international terrain.”

This special issue of NANO is dedicated to exposing the historical cultural and political logic of the genre, and highlighting the potential for new narratives to challenge past politics, break free from conventions of the past, and offer a vision that transcends national boundaries, fixed gender binaries, and exclusionary racial discourses. Understanding the historic journey of captivity narratives from Puritan America and Mary Rowlandson to Patty Hearst and Kimmy Schmidt is one part of transforming the logic of that narrative, from a narrative that served to justify colonial aims and genocide, to one that could remind us of the captives in our midst, whether they be women trapped against their will in rooms with powerful media executives, children in cages at the border, or the millions currently behind bars in the U.S. carceral system. These are stories that must be told.

Works Cited

“700,000 Female Farmworkers Say They Stand with Hollywood Actors Against Sexual Assault.” Time, 10 Nov. 2017, https://time.com/5018813/farmworkers-solidarity-hollywood-sexual-assault/.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 1991.

Burke, Tarana. “#MeToo Founder Tarana Burke on the Rigorous Work That Still Lies Ahead.” Variety, 25 Sept. 2018, https://variety.com/2018/biz/features/tarana-burke-metoo-one-year-later-1202954797/.

Castiglio, Christopher. Bound and Determined: Captivity, Culture-Crossing, and White Womanhood from Mary Rowlandson to Patty Hearst. The U of Chicago P, 1996.

Faery, Rebecca Blevins. Cartographies of Desire: Captivity, Race, and Sex in the Shaping of an American Nation. U of Oklahoma P, 1999.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. Broadway Books, 2006.

---. The Terror Dream: Myth and Misogyny in an Insecure America. Reprint edition, Picador, 2008.

Garber, Megan. “Pop Culture’s Fascination with Captive Women?” The Atlantic, 6 July 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/07/pop-cultures-fascination-with-captive-women/490067/.

O’Sullivan, Shannon. “Who Is Always Already Criminalized? An Intersectional Analysis of Criminality on Orange Is the New Black.” The Journal of American Culture, vol. 39, no. 4, 2016, pp. 401–12.

Rex, Cathy. Anglo-American Women Writers and Representations of Indianness, 1629-1824. Ashgate, 2015.

Rowlandson, Mary. “A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, Also Known as The Sovereignty and Goodness of God.” American Captivity Narratives: Selected Narratives with Introduction, edited by Gordon Sayre, Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Sayre, Gordon, editor. American Captivity Narratives: Selected Narratives with Introduction. Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Scheckel, Susan. The Insistence of the Indian: Race and Nationalism in Nineteenth Century American Culture. Princeton UP, 1998.