Stupid Love: Notes on a Lyric by Lady Gaga

by Patrick Clement James

Published June 2022

Abstract:

“Stupid Love: Notes on a Lyric by Lady Gaga” situates Lady Gaga’s pop song “Stupid Love” within Platonist and Pauline philosophies on love. Deploying a fragmented, queer reading practice, the essay makes several propositions on love and philosophical rationalism, beginning with Gaga’s desire for “stupid love.” Along the way, the author consults an eclectic group of thinkers—from Erasmus to Wittgenstein—in order to clarify the particular modes of erotic love and theology at play within Gaga’s lyrics. Specifically, this essay traces a strand of Christian thought through Gaga’s corpus, in which love serves as the means for a radical revision of values. These notes suggest that Lady Gaga’s various invocations of love, grace, and original sin offer a queer, erotically charged reading of Christian soteriology.

Keywords: Lady Gaga, pop music, love, philosophy, theology, queer theory

—Lady Gaga says: “I want your stupid love” (“Stupid Love”).

—Lady Gaga says: “I don’t need a reason” (“Stupid Love”).

—I don’t need a reason. I’m not sorry I want your stupid love. Does anyone deserve to be loved? Do I need a reason to love you? And, for that matter, what does it even mean to have a reason: to be wise, rational, to make a choice based upon one’s wisdom?

—In my pursuit of you, I found Gaga. I found a large, cavernous room in Bushwick, with LED lights and vodka. And boys in short shorts and canvas shoes. I found a hypnotic repetition: Can’t read my—Can’t read my—Can’t read my—Can’t read my—Can’t read my—on and on, until I found myself suddenly held by you, kissed by you, fondled by you. The beat dropped; our differences vanished. Gaga taught me about Oscar Wilde, surfaces, and Susan Sontag. She taught me that attention to form is the cruel path toward beauty. She taught me that there is more to art than my liberal pieties. She taught me to do my research. And she taught me what St. Paul had been trying to tell me all along: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (NIV, Galatians 3:28). In the large, cavernous room, entwined in that bacchanal, I lost my skin. I lost my cock. I lost my words. I lost my reasons to not love you.

—I am not wise. I am not reasonable. I choose, instead, to follow winding paths through cities, dark alleys, parks and public bathrooms: the meaningless cruelty of humans—betrayal, insult, accusation. And other wounds of the heart: a sloppy kiss, bad poetry, too much red wine. I look for you. I would follow you anywhere: destitution, homelessness, bankruptcy, degradation, humiliation, pain. If you were to ask me why I want you, I would have no reason. I am irrational. I want something unreasonable; I want you.

—Am I stupid or am I sick?

—In Erasmus of Rotterdam’s mock encomium on stupidity, Praise of Folly (1511), the personification of foolishness, Folly, informs us that “Anoia, Madness,” is a member of her household (18). As courtier, lunacy is present “along with the rest of [Folly’s] attendants and followers” (Erasmus 17). Standing with Anoia, in Folly’s court, are Philautia (self-love), Kolkatia (flattery), Lethe (forgetfulness), Misoponia (idleness), Hedone (pleasure), and Tryphe (sensuality) (Erasmus 18-19). The arrangement, wherein madness is nested within foolishness, makes the ambiguous differences between the two difficult to parse.

—I’d like to suggest, however, that there is a difference between clinical mental illness, in a materialist sense, and quotidian irrationality. As much as there is to criticize in Freud’s corpus, I must acknowledge perhaps his greatest contribution to my understanding of the human experience, the unconscious: “impulses of which one knew nothing directly” (Freud 19). Or, as I like to think of it: people don’t always know why they do the things they do. Irrationality, in the Freudian sense, is a universal condition of human life. This is not the same as mental illness (conditions such as, for example, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia). I am not a psychologist or a medical doctor; I make no pretense to that expertise. However, I am interested in reframing illogic, stupidity, and irrationality as methods for attaining more profound experiences of love. I am interested in stupid love.

—The word stupid, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, comes to us etymologically from the Latin stupidus: “dazed, stunned, speechless” (“stupid, adj”). Stupidity’s linguistic association with speechlessness feels especially noteworthy because it activates a conceptual kinship with the word dumb, which is Germanic in origin, and means: “destitute of the faculty of speech…” (“dumb adj”). In both cases, the etymological DNA of these words inscribe foolishness with an attending speechlessness, a loss of words, inarticulation, aphasia. For example, the angel Gabriel, in the Gospel of Luke, stupefies Zechariah, rendering him “dumb, and not able to speak” (KJV, Luke 1:20). However, it is Zechariah’s cognitive dissonance—his inability to wrap his head around his sensory experience of the angel (not to mention the angel’s prophecy regarding his son, John the Baptist)—that produces his speechlessness. In other words, the speechlessness arises out of a kind of short-circuiting of the mind. Zechariah is dazed and confused and punished by the angel, incapable of metabolizing the sensory and illogical information contained within the angel’s message. He cannot comprehend it. He is struck dumb by his vision.

—Or, as Gaga sings in her song “Speechless”: “How? How? How?” Incredulity is the source of her speechlessness. “I can’t believe…” she states repeatedly, gazing at her beloved, a sort of bad-boy Jesus-type with “James Dean glossy eyes” and “long hair.” “I’ll never talk again,” she vows, “Oh boy you’ve left me speechless….” (Lady Gaga, “Speechless”).

—In Tales of Love (1983), Julia Kristeva writes: “The speaking being is a wounded being, his speech wells up out of an aching for love…” (372). This psychoanalytic supposition proposes that speaking subjects are inextricably wounded; the silent are healed. The proposition suggests that the dumb have been made whole. The force of love’s consummation has snuffed out their constant babble. Aphasia is a symptom of an all-powerful love. A love with no name. A love that no mere mortal can name.

—I find the correlation between speechlessness and stupidity to be somewhat ironic. The biggest fools I know babble incessantly. Or, as the Scarecrow says to Dorothy: “Some people without brains do an awful lot of talking” (The Wizard of Oz).

—As Wittgenstein famously states in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922), “the limits of the language (the language which I understand) mean the limits of my world” (27). Thus, he concludes, “whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent” (27). What I cannot know, I cannot say. There is a limit to language and a limit to intelligence; therefore, “what lies on the other side of the limit will be simply nonsense” (Wittgenstein 27). To be silent is to venture into the unknown, to risk stupidity and foolishness. But, perhaps, it would be better to not speak of this? I’m not sure I understand Wittgenstein; consequently, I should not speak of him.

—Have I told you lately how beautiful you are?

—In A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments (1977), Roland Barthes writes, “Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other” (73). But you—your beauty—has made me speechless, skinless. I fall out of myself, untethered to form. I am swallowed, digested. And suddenly I realize—I have wanted to eat you for so long, and only now do I understand that you have eaten me. “You ate my heart. You ate ate ate my heart” (Lady Gaga, “Monster”).

—Walter Benjamin says, “the only way of knowing a person is to love that person without hope” (62). My experiments in love have taught me that this claim is soft-minded nonsense. Love grants no knowledge of the beloved. I love you, but I know nothing about you. You remain, as always, unyielding to my comprehension. Loving you has made me stupider than I have ever been. And, my darling, I love you without hope. I am hopelessly devoted to you.

—My idiocy feels almost pathological. When I tell you I want your “stupid love,” is there no alternative? Or do I make this choice willingly? Irrationality, as a concept, implies a loss of agency; one is struck dumb by the outrageousness of a particular phenomenon, as if one is cursed by the angel. In contrast, foolishness suggests a choice. One chooses a lover wisely or foolishly. But, when I try to apply such a framework to you, my beloved, I am rendered both speechless and choiceless. My “stupid love” for you, unwise beyond any measure, is not something I have chosen; it is my vocation. You have extinguished my voice. Now, your calling echoes endlessly.

—Donald Gwynn Watson points to the carnivalesque absurdity of Praise of Folly, how Erasmus incorporates the contemporary notion of “the world turned upside down”—famously observed by Mikhail Bakhtin’s analysis of the carnival—into a text that has so often been studied for its classical allusions (333). The text proves there is “more than mere analogy,” Watson claims, “between carnival laughter and the joy of Christian faith” (335). Watson’s genealogy of Folly’s speech springs not so much from classical Latin texts and culture, but from the fifteenth and early sixteenth century Fête des Fous, wherein young, unmarried men from the abbeys partook in “licensed reversal of order or rites of status reversal.” These particular celebrations were deliberate acts of transformation, in which “the rules and norms of everyday business were suspended” (Watson 337). The overarching philosophy of the carnivalesque, the Fête des Fous, and by extension, Praise of Folly, is that “folly is the universal condition of man” (Watson 340). (Or as the Cheshire Cat tells Alice, “We’re all mad here” [Carroll 42].) This conviction reconfigures Folly’s summation of Christ, wherein his foolishness becomes the means of a divine redemption—a soteriological legerdemain: “Christ too,” Folly informs us, “though he is the wisdom of the Father, was made something of a fool himself in order to help ‘the folly of mankind’ when he assumed the nature of man and was seen in man’s form” (Erasmus 125-126). In other words, Christ’s stupid love for mankind, as expressed through the incarnation, becomes the lynchpin of Christian soteriology in Erasmus’ analysis. God becomes man so that man becomes god so that man becomes like god. Topsy turvy. I should not be surprised. For St. Paul instructs the Corinthians, “the message of the cross is foolishness for those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (NIV, I Corinthians 1:18).

—I have turned myself upside down for you. You have turned the world upside down for me. My insides are my outsides. The top is the bottom. You are in me; you are out of me. I have no idea, anymore, where I end and you begin. I am neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free. I am neither male nor female.

—Plato would say I am the unreasonable lover. The irrational suitor. Or, as Beyoncé so beautifully describes it, I am “crazy in love (uh oh, uh oh, uh oh, oh, no, no)” (“Crazy in Love”). In the Phaedrus (370 BCE), Socrates recognizes that erōs is an “unreasoning desire that overpowers a person’s considered impulse to do right…” (Plato 238C). However, instead of repudiating this madness, as in Lysias’ cynical speech, Socrates affirms that “the best things we have come from madness, when it is given as a gift of the god” (Plato, Phaedrus 244A). Much like “prophetic trances,” madness is the purview of artists: it is, according to Socrates, “…the kind of madness that is possession by the Muses…” (Plato, Phaedrus 245A). For Socrates, madness is an ontological necessity for both love and art: “If anyone comes to the gates of poetry and expects to become an adequate poet by acquiring expert knowledge of the subject without the Muses’ madness, he will fail, and his self-controlled verses will be eclipsed by the poetry of men who have been driven out of their minds” (Plato, Phaedrus 245A).

—Like poetry and prophecy, erōs is a “god-sent madness,” designed to “ensure our greatest fortune” (Plato, Phaedrus 245B). Indeed, in his dialogue with Phaedrus, Socrates illuminates how erōs provokes the soul’s remembrance of the divine—what the soul discovered on the ridge of heaven, as it marched in procession with the gods. Through this framework, erotic love is the means by which I remember my own primordial madness, my own extra-universal vision of platonic forms. It is the means by which I love my god, worship my god—by which I look on the world with the eyes of a god and see what a god sees. Or, as Gaga sings with the band Chic: “I’m your ladder, I’ll be your path” (Rodgers).

—Are you my ladder to the ridge of Heaven? Are you my path? The way?

—According to Diotima in The Symposium (385-370 BCE), love is between good and bad, between beautiful and ugly, “between wisdom and ignorance” (Plato 204a). She compares erotic desire to “having right opinions without being able to give reasons for having them” (Plato, Symposium 202a). (“I don’t need a reason. Not sorry I want your stupid love” [Lady Gaga “Stupid Love”].) Erōs is in the interstices: “he’s between mortal and immortal…a great spirit...between god and human” (Plato, Symposium 202d-e). This daimonic figuration places erotic love at the threshold between the sacred and mundane, the banal and divine. It is a means by which one moves between these two spheres. Personified as Erōs or Cupid, the daimon “[carries] messages from humans to gods and from gods to humans” (Plato, Symposium 202e). He is the interpreter of sacred signs and symbols. And, in the Phaedrus, he is shown to be the generator of the soul’s flight toward heaven. However, the interstitial positionality of the figure inevitably invokes lack. Possessed by the daimon, I want, I want, I want, I want, I want, etc. I want you; I want your beauty; I want to eat you; I want you to eat me (“Show me your teeth”); I want to see what a god sees; I want wisdom (Lady Gaga, “Teeth”). If I want wisdom, then I must be stupid. Philosophers love wisdom; they want wisdom. In their lack, all philosophers are stupid. In my stupidity, I am like Cupid—I am “always poor…tough with hardened skin, without shoes or home;” I always sleep “rough, on the ground, with no bed, lying in doorways and by roads in the open air;” I always live “in a state of need” (Plato, Symposium 203d).

—Perhaps you feel sorry for me, debased and humiliated by my love for you. Fear not: to be wise about love makes one “a man of the spirit, while wisdom in other areas of expertise and craftmanship makes one merely a mechanic” (Plato, Symposium 203a). The wisdom of the lover is madness to the bureaucrat, the engineer, the scientist, the mathematician. The poet writes by the light of the moon—the lunatic. And yet, while gripped by the tight fists of gods—either muse or Cupid or the bright and terrible vision of you—the lover sneers at the wisdom of men. I sneer at the wisdom of men. What use is the mechanic to me as I writhe in my passions for you? Some may call for the priest and demand an exorcism. Like Linda Blair, possessed by the daimon, I say shocking things; but I dare not chase the ghost from my ribcage. My ecstasy is stupid; I love it.

—Love made me do it. Isn’t that what Christ said as the Roman soldiers nailed him to the cross? I love the world so much that I give my incarnated self, that whoever believes in me may have eternal life. Yes, Erasmus is just so right: “The happiness which Christians seek with so many labours is nothing other than a certain kind of madness and folly” (128). Love made me to do it; I had to do it.

—Needless to say—but I will say it—Erasmus locates within the folly of Christ an intersection between Christian soteriology and Platonic myth. Folly teaches us that “Christians come very near to agreeing with the Platonists that the soul is stifled and bound down by the fetters of the body, which by its gross matter prevents the soul from being able to contemplate and enjoy things as they truly are” (Erasmus 128). Plato, Folly, and St. Paul agree that my body prevents me from seeing you as you truly are. Therefore, to approach you I must abandon embodied knowledge, empiricism; I must become dumb, silent; I must become blind like a prophet, the skinless lover, and see you by means other than my own eyes, my own flesh. I must speak to you without a tongue.

—In Lady Gaga’s album Born This Way (2011), the artist places herself within a Pauline soteriology. Though her soul is bought and paid for by the stupidity of Christ, her earthly body still clings to the lowly vices of this world. She bears a vexing tension between the trajectories of spirit and flesh. For example, her single “Judas” figures Gaga as Magdalene, caught between her foolish love for Jesus and her worldly entanglement with the bad boy Judas (we’ve all been there). “I’m just a holy fool, oh baby it’s so cruel,” she cries, “but I’m still in love with Judas, baby” (“Judas”). She goes so far as to make the polar forces pulling at her soul and body explicit: “I wanna love you / But something’s pulling me away from you / Jesus is my virtue / And Judas is the demon I cling to...” (“Judas”). The artist swings between the poles of sin and redemption, death and salvation. Captive to Judas, she repeats his name in babbling echolalia, until their two names merge: “Judas—Juda-ah-ah, Judas—Juda-ah-ah, Judas—Juda-ah-ah, Jud-as-ga-ga!”

Her situation calls to mind a framework of addiction, or daimonic possession, the sense that something is alive in her that she cannot control. And, in this manner, it echoes a Pauline theology. As St. Paul writes to the Romans:

I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do. And if I do what I do not want to do, I agree that the law is good. As it is, it is no longer I myself who do it, but it is sin living in me. For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want to do, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it. (NIV, Romans 7:15-20)

The effect is vertiginous. Two desires dwell inside Gaga: the body and the daimon. She is pulled and twisted. She suffers. Therefore, according to this logic, something in her must be crucified for her to achieve salvation. Likewise, St. Paul instructs the Romans: “For we know that our old self was crucified with him so that the body ruled by sin might be done away with, that we should no longer be slaves to sin—because anyone who has died has been set free from sin” (Romans 6:6-7). Gaga’s pleading for Jesus is a pleading for death—as is, ultimately, the plea of all Christian supplicants: a desire to die in Christ, in order to resurrect with him, through him, transformed by love from something earthly and temporal into something divine, godlike, holy, eternal. This dynamic is called grace, for as St. Paul tells the Ephesians: “It is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast” (NIV, Ephesians 2:8-9).

—As I wander this lonely road toward you, I pass by Nietzsche, and he rolls his eyes at me. I say, “What?” And he says, “You’re such an idiot.” I say, “I can’t help it; it’s not my fault.” He says, “You’re such a fucking idiot.”

—It is important to note that Nietzsche is stupid, just like me—that is, before he goes clinically insane. Until then, alas, we love different things. We are both madly in love.

—St. Paul’s thesis: the stupidity of Christian love is that it requires the self to be destroyed. It requires an act of subjective silence. A loss of voice. A loss of position. A loss of a thesis. A loss of coherence. One must be foolish enough, in a worldly sense, to unite oneself with Christ in his crucifixion—to be united with Christ in his resurrection. To be clear, this requires death of the supplicant—death, which makes life possible. For as Christ said, “Whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it” (NIV, Matthew 16: 25). Therefore, the worldly self must be destroyed, crucified, washed away by holy water.

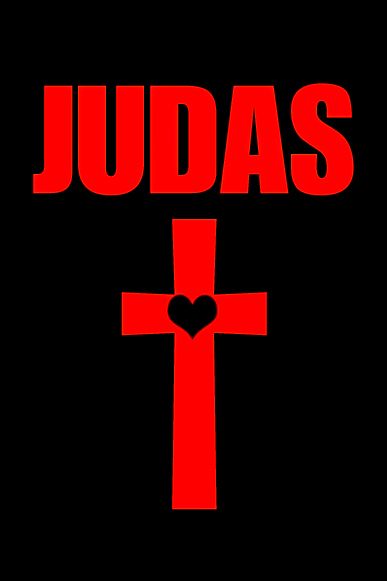

—Gaga makes this productive death somewhat explicit in the imagery attending her work. For example, the artwork for her single “Judas” portrays a cross with a blackened heart at the center, an image that alludes to Martin Luther’s rose.

In Gaga’s symbolism, the blackened heart is crucified on a red cross. Above this image the name Judas is inscribed. Gaga’s heart is the unwashed heart, captive to Judas—the unredeemed heart, the worldly heart, the antediluvian heart. The cross upon which she is crucified burns red. Luther’s Rose, a symbol of the reformer’s soteriology, presents the inverse.

As Luther wrote in a letter to Lazarus Spengler in 1530, “there is a black cross in a heart that remains its natural color. This is to remind me that it is faith in the Crucified one that saves us” (280). For Luther, through the process of crucifixion, Christ’s cross is blackened, but the heart beats red, which Luther recognizes as the symbolic color of the natural organ. Luther believes that salvation “leaves the heart its natural color” because salvation does not “destroy nature, that is to say, it does not kill us but keeps us alive” (280). Indeed, Christian theology states that just as Christ was resurrected in both body and soul, so shall the supplicant be redeemed likewise.

—“Judas” is not the only song to find Gaga at odds with herself. In the prologue to her video for “Born This Way”—the album’s eponymous song—Gaga states her credo, “the manifesto of mother monster” (Lady Gaga, “Born This Way”). Her statement invokes elements of cosmogony, science fiction, and human reproduction to create an etiology for morality.

On GOAT, a government owned alien territory in space, a birth of magnificent and magical proportions took place. But the birth was not finite, it was infinite. As the wombs numbered and the mitosis of the future began it was perceived that this infamous moment in life is not temporal, it is eternal. And thus began the beginning of the new race; a race within the race of humanity; a race which bears no prejudice, no judgment but boundless freedom. But on that same day as the eternal Mother hovered in the multiverse another, more terrifying, birth took place: the birth of evil. And as she, herself, split into two, rotating in agony between two ultimate forces, the pendulum of choice began its dance. It seems easy, you imagine, to gravitate, instantly and unwaveringly, towards good. But she wondered, “How can I protect something so perfect without evil?” (Lady Gaga, “Born This Way”)

Gaga does not represent birth as a single, discrete event. Birth is “eternal,” an “infinite” chain reaction. However, simultaneously within “the multiverse,” the artist gives birth to evil, which is articulated through an image of Gaga delivering an assault weapon through her vagina. Through the birth of goodness and the birth of evil, Gaga is “split into two, rotating in agony between two ultimate forces,” and “the pendulum of choice [begins] its dance.” Gaga portrays herself as a source of both goodness and evil. Eternally born and eternally destroyed, she bobs in the interstices with erōs—a body tainted with sin. Thus, she embodies the Christian concept of original sin: “Baby, you were born this way” (Lady Gaga, “Born This Way”). Gaga is unstable, and thus she is dynamic. Bound to erōs, she is host to a spectrum of morality: good, evil, everything in between.

—The music video for “Judas” makes Gaga’s conversion explicit. Amid the push and pull of Jesus and Judas, Gaga is flooded by the salty sea and washed away, reduced to nothing. This flood invokes not only the deluge by which God purified the world in Genesis, but it also points to the ritual of baptism (NIV, Genesis 6:18). It is through this sacrament, Martin Luther claims, that “the Old Adam in us should by daily contrition and repentance be drowned and die with all sins and evil desires, and that a new man should daily emerge and arise to live before God in righteousness and purity forever” (Luther’s Small Catechism 17).

In the video, as she bounces back and forth between her devotions to Jesus and Judas, Gaga presents herself before the ultimate baptismal font: the sea. The “holy fool” stands proud, majestic, imperious, and autonomous, only to be dissolved by the holy water of Christ’s annihilating love (Lady Gaga, “Judas”). Where there once was a Gaga, there is no Gaga. The flood disintegrates subjectivity. Gaga is eviscerated, silenced, quenched, swallowed by the sea, just as Christ was swallowed by the tomb.

—What will you destroy in me? What part of myself must I let you wash away in order to become like you? To give myself to you? To be worthy of you? Your love for me is my greatest opportunity for transformation—painful and productive. Poor Abraham had to be circumcised. And us? I cannot tell you how much I have ached for you. Like John Donne, I want you to “batter my heart;” please, I want you to “o’erthrow me, and bend / Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new” (30, lines 1-4). Kinky, sure. This is the nature of grace. But, also messy. How did grace become so graceless? But, also stupid. Also, necessary.

—Let us speak of your stupid love, our bad romance. Certainly, I am an idiot; but you have cobbled yourself into a body, if only to meet me as a body (“hair…body…face” [Lady Gaga, “Hair Body Face”]). Arms that one can touch; lips to kiss; armpits to smell. It would be so easy to say: “You have no idea what it feels like to be me, to suffer the way I suffer.” But you have foiled me even in this. How could I say such things when you stand in the world, walk through the world, know hunger and lust and sweat just as I do? You eat, you drink, you piss, you shit. Only a fool would agree to such conditions. But here we are. Foolish me and foolish you. Here we are in these bodies, growing ugly and wrinkled. What prompted such generosity on your part? Only a fool would take off a crown in order to be a peasant. Only a fool would ride into the city victorious, merely to end up executed. Only a fool would step from behind the veil to appear before mortals, to consort with fools. Why would you do something so stupid? I imagine this was the reason: you were lonely; you wanted to know what it felt like—to feel pain, degradation, and ruin; you saw me in my grief, and your heart ached for my sake; you longed for me, yearned to touch me as a body touches another body. I imagine you thought to yourself: “Since he is an animal, I will come to him as an animal. I will make myself stupid to love this stupid boy.”

—"Baby, you’re sick. I want your love” (Lady Gaga, “Bad Romance”). I want your stupid love.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. Translated by Richard Howard, FSG, 1978.

Benjamin, Walter. One-Way Street. Translated by Edmund Jephcott, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Harvard UP, 2016.

Beyoncé, ft. Jay-Z. “Crazy in Love.” Dangerously in Love. Columbia Records, 2003.

The Bible. Concordia Self-Study Bible: New International Version, Concordia Publishing House, 1986.

The Bible. King James Version, Christian Art Publishers, 1999.

Carroll, Lewis. Alice in Wonderland Collection. Enhance Media Publishing, 2016.

"dumb, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford UP, Mar. 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/58378.

Donne, John. “Holy Sonnet XIV.” The Holy Sonnets. Vicarage Hill P, 1999.

Erasmus. Praise of Folly. Translated by Betty Radice, Penguin, 1971.

Freud, Sigmund. “An Autobiographical Study.” The Freud Reader, edited by Peter Gay, Norton, 1989.

Kristeva, Julia. Tales of Love. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez, Columbia UP, 1987.

Lady Gaga. “Bad Romance.” The Fame Monster. Streamline and Interscope, 2009.

---. “Hair Body Face.” A Star is Born. Interscope, 2018.

---. “Judas.” Born This Way. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2009.

---. “Monster.” The Fame Monster. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2009.

---. “Speechless.” The Fame Monster. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2009.

---. “Stupid Love.” Chromatica. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2020.

---. “Teeth.” The Fame Monster. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2009.

“Lady Gaga – Born this Way (Official Music Video).” YouTube, uploaded by Lady Gaga, 27 Feb. 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wV1FrqwZyKw.

“Lady Gaga – Judas (Official Music Video).” YouTube, uploaded by Lady Gaga, 3 Mar. 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wagn8Wrmzuc.

Luther, Martin. Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions, a Reader’s Edition of the Book of Concord. Translated by Paul Timothy McCain, Concordia Publishing House, 2005.

---. Luther’s Small Catechism with Explanation. Concordia Publishing House, 1943.

Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff, Hackett, 1995.

---. The Symposium. Translated by Christopher Gill, Penguin, 1999.

Rogers, Nile, Chic, ft. Lady Gaga. “I Want Your Love.” It’s About Time. Virgin EMI, 2018.

"stupid, adj., adv., and n." OED Online, Oxford UP, Mar. 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/192218.

Wattson, Donald Gwynn. “Erasmus’ Praise of Folly and the Spirit of Carnival.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 2, 1979, 333-353.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by C. K. Ogden, Dover, 1999.

The Wizard of Oz. Directed by Victor Fleming, performances by Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, and Bert Lahr, Warner Brothers, 1939.