Community in Competition: The American Birkebeiner Cross-Country Ski Race

by Tim Donahue

published May 2014

I am a competitive cross-country skier who lives in Manhattan. Almost all of my workouts are done alone, circling the Central Park loop on wheeled rollerskis in the evening, after work, when the traffic calms down and the lights are just bright enough to see where I’m going. At the school where I teach, people hear I ski and they ask, “How were the slopes?” I tell them they go up and down. It’s all rather abstract to them, I think; but to me, it’s periodized training blocks, five distinct heart rate zones, and an arsenal of Craft sports apparel with breathable microclimates.

Every year for the past dozen, I’ve tried to maintain a delicate balance among the challenges of staying fit, finding time, sparing the tender shards of knee cartilage that remain, rarely getting on snow, waxing skis on my kitchen counter, and feeling confident that my physical shortcomings can be outpaced by my mental capacity to overcome all this. Five or so times a winter, my wife and babe allow me to bridge the certain gap between my singular pursuit and the community that inspires it—I go to races.

Cross Country Ski Association of America representative Chris Frado reports that of the 314 million Americans, over 30 million are Nordic skiers. This seems like a generous number, considering there are currently just two U.S. men, Andy Newell and Simi Hamilton, who make a living as full-flight U.S. Ski Team “A” members. Every year, I mess with my high school students, offering them extra credit on quizzes if they can name just one World Cup Nordic skier—they never can! Compare this to Norway, where an article by Julie Ryland in The Norway Post states “60 percent of Norwegians rate cross-country as a sport of high interest.”

It is only fitting, then, that America’s premier ski event, the Birkebeiner, steals from Norwegian tradition. According to the race organization’s website, “[i]t started in 1206. Birkebeiner skiers, so called for their protective birch bark leggings, skied through the treacherous mountains and rugged forests of Norway’s Osterdalen Valley,” carrying the 16-pound Prince Haakon to safety against a throng of enemies. The Norwegian Birkebeiner sells out in hours and is capped at 16,000 entrants, many of whom carry honorary 16-pound packs. The American version of the race is in late February, when up to 13,000 skiers pilgrimage to the hardwood forests of northern Wisconsin, not far from the Canadian border, for what may be one of the hardest and sweetest endurance competitions in the world—the American Birkebeiner.

Getting there, for me anyway, means rolling through Harlem to LaGuardia on the M60 bus, with my ski bag and suitcase, early in the morning, and then flying to the Twin Cities before continuing for four more hours into deepest Wisconsin, with its windblown fields of cornstalk stubbles pointing through the snow. Amid all this space and travel time, the mind softens. When I approach Hayward, where the race finishes, I see ice sculptures and real sculptures of skiers, and grown men playing accordions in Leiderhosen. For once, I am not the only one thinking about ski wax.

At the Hayward Middle School, where I pick up my bib, I find the familiar mix of festival and nerves. “The Birkie,” like prisons, assigns everyone a number. In this case, the identifying stamp reflects a skier’s placement in prior years—that’s one of the stoic honesties involved with skiing 50 kilometers, sometimes in sub-zero temperatures. There are 12 “waves” of skiers now, who head off in groups into the high hundreds. The elite men and women finish in just around two hours; the “newbie” wave 9 and 10 skiers might clock in at over six. But everyone is invited to the carbo-load spaghetti dinner at the Lutheran Church and to pose, side-by-side, on the “world’s longest ski.” Even in their flannel shirts there in the gym, it’s not hard to tell who belongs where—the wave three skiers deliberating whether the 30 gram, $130 vial of pure fluorocarbon wax is worth 5 minutes off their finish time; the 20-year Birkie vets making the same jokes about hot toddies at the feed stations; the wave 9 and 10s trying to understand how the parking system works. I suppose I appreciate that they take note of the giant “42” someone has scrawled on my elite wave race bag, advertising my 42nd place result from the prior year, when I finished in 2 hours, 11 minutes, 9% behind the winner, Tore Martin Gundersen. I’ll confess that in our evolution from gladiators, Vikings, and birch legging warriors, where accomplishments are as vague as passive aggression, this offers tangible evidence that I have achieved, at least, something.

There are about 200 skiers in the elite wave and we fan out 40-wide across a small airstrip in Cable, Wisconsin, where the point-to-point race begins. Placement here is self-seeded, and is usually determined by bib number, thigh development, and adrenaline—the order of these considerations varies by ego. But it matters little, as the wide trail runs flat for 3k, then turns to climb several steep hills along a power line. Here is where the separations begin and the “trains” of skiers coalesce before solidifying at 5k, when the trail narrows into the woods.

Although a number of volunteers and Viking-helmeted fans line the course, skiing has no referees. It has no real form of defense; there is certainly no contact allowed. And yet, in this race that climbs 4,587 vertical feet over 31 miles, with packs moving along in the dozens, several unwritten rules of conduct emerge. I learned the most important one the first time I ever did this race: don’t spaz. Fearing my train was moving too slowly and thus letting the faster skiers slip away, I tried to pass up a hill by inaugurating my own, third lane. When the trail inevitably did not allow for this, I tangled with a fellow skier, he went down, and I received colorful language. For several miles I ruminated upon how I had disturbed the train’s trust.

A well-conditioned train is one of the most beautiful things I have experienced in sports—and I’m convinced it’s why most of the best marathon skiers journey back to this event. Done properly, it allows a feeling of levitation, a sense that the burden of speed and distance can be mitigated by impromptu alliances full of words that are known, but not said.

The “high point” of this race comes early, at 13 kilometers, and the next 25k, fully half the race’s distance, roll along the birch forest mildly, inviting the silent orchestration. On gentle downhills, the lead skier reaches into his waterbelt for a drink and everyone follows. A skier ends his “pull” of the pack, someone else takes over at the front, and we let him in. Even at the highest level, this camaraderie exists: during the early stages of a men’s event at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, there was a pile-up in front of a narrow bridge; the pack waited for its fallen to rejoin the group.

This tacit trust not only helps with the physical rigor, but it frees the grating and exhausting menace of anxiety as well. A group that can move efficiently and responsibly, without the high-school antics of constant attacks and “boxing out,” will simply spare its energy better. As Mikey Sinnott, the 2013 points winner in the U.S. Super Tour pro Nordic circuit, says, “Quite simply, it’s easier to follow than it is to lead.” And in this event, where every skier must decide how to expend a limited store of fuel, this matters a great deal. According to Øyvind Sandbakk and Hans-Christer Holmberg of the Swedish Winter Sport Research Center, “[m]ass start races accentuate the importance of both drafting economically behind other skiers and obtaining a position that is least problematic and allows optimal utilization of one’s individual strengths.” Indeed 10 of the 12 Olympic cross-country ski competitions now involve mass starts.

In a good train, there are the sounds of skis gliding, poles squeaking in the snow, and the wind swaying tall trees. I’m so taken by the union of all this, it can feel like we’re almost not racing at all.

But of course, we are. Just before the 40k mark, when a new, 10k race will begin, there is “Bitch Hill,” which rises 90 feet in 200 meters. Its hype makes it taller than it really is, but the mind can play tricks on wearied skiers, and it’s tiring enough trying to decide what to do here. Some attack this, hoping to “fracture” the alliance that brought them here together; some keep their powder dry, still reliant on the train’s nucleus to gobble up the breakaway when they weary from the surge. But almost inevitably, things fall apart on or near this hill. A season’s worth of training–upwards of 500 hours for some, who rollerski on the hottest days of August with this moment in mind–comes down to this denouement.

Here, it becomes an individual race again. But unlike a straight 10k mass start, where people might step on each other’s poles to shave precious seconds, the urgency gives way to respect. Everyone here has been charcoal-aged and survived the Scotch equivalent of 12 years to earn a spot. Exhaustion clips verbosity, but I’ve heard the most gracious, communal things said in these times: to a fading skier up Duffy’s Hill (near the 45 km marker) “Don’t lose contact!”; from a skier who looks fresh and hungry, “Let’s go get those guys!”; from a bunch of frothing men with icicles on their beards, the gleeful cry of a wolfpack. It’s here where I best understand that the word “passion” comes from the Latin verb “to suffer.”

But before the 500-meter finish across the snow-covered streets of Hayward, the course throws up its most deceptive divide between the integrity of the group and the individual pursuit of results. Racers must cross a frozen lake for about 3 kilometers: it is utterly flat and wide-open and often windy. Four of the five years I have done this race, a de facto “honor code” has prevailed here—unless you are clearly dying or surging, you more or less help each other across this narrow ribbon of grooming, and then try to rip each other apart in the final stretch. As Sinnott insists, “If you are not with the leaders, then work together to go fast. Who cares if you won your train? You [will be] slower and further back because of your selfishness.” But my last experience here at the lake was demoralizing—it brought down the morale.

It may be a symptom of the event’s popularity, but my train in 2012 was so large that it defeated its own purpose. For most of the race, more than 40 of us were going at it, double-wide. I knew several of them—one had loaned me wax the year before, another had put me up at his house in Tahoe, another had raced with me all over New England. But just as groups can be magnanimous, they can also revert to the lowest common denominator. Those with faster-gliding skis took stupid, dangerous risks trying to pass on downhills. Those who veered over to get a drink at the aid station that day had a hard time getting back in. Even after someone ended his turn pulling at the front, it wasn’t a done deal that he’d be let back in. Then, there were the types Sinnott calls the “jerks.” “The least respected athlete,” he says, “is the one who sits in the back and waits until the end to sprint ahead and win. But that is also usually the most successful athlete. There are no real repercussions other than trash talk, and possibly a difficult time at the next race when athletes will not let him in to the train, or will break his pole.”

Everyone was desperate to break away that day, but the sheer force of the group sucked them back. As Sinnott says, “It is considerably harder to drop people when they are right on your tail, because of the draft.” No one seemed to want to get dropped and no one could get away. We were trapped—all alone and all together.

This final pass of the lake, then, offered dwindling moments to move from 70th place to 40th—a make or break difference in pride and perceived skill to those among us who temporarily equate results with self-worth. Even in the melee right then, I thought of my times on the Long Island Expressway, where cars muscle in from the exit lane at the very last second. It wasn’t skill so much as rudeness that divided those 30 places into 30 seconds that day. I remember crossing the line and thinking, “I’m done with this race—I won’t be back.”

In the large changing tent, where wet Spandex came off and steam rose from tired bodies, we processed the race. Everyone seemed dissatisfied with the collective immaturity. Ideally, we use each other to race together; on this day, we used each other to beat each other. Our pack was eclectic—eager kids and marathon masters—and no one could initiate an identity. It wanted to be a working group, but we wouldn’t allow it.

Fortunately, there are the post-race rituals that make it easier to come together and soften the edges. There’s the endless bowl of chicken soup ladled by an amazing number of volunteers, there’s the moment when you are finally still and take in the enormity of the scene, where a whole town is lined six-deep with fans yelling in the cold just to glimpse their Valentine going by, and there’s the Moccasin Bar. A round of Leinenkugel’s at 11:00 a.m. has a way of making you forget that guy who stepped on your ski at 35k. Inevitably, we spill out onto the frozen lake and watch the endless stream of slower skiers, slogging into their fifth and sixth hour, giving it everything they have. It’s an image I keep with me all year.

Mercifully, the Birkie is on a Saturday, which leaves the balance of the weekend to rest upon that year’s harvest of laurels and enjoy the universal human pleasures of sleeping and eating. When I wake from a prodigious nap and head out into darkening “downtown” Hayward for dinner, I see the snow is already off the roads, now lined with caravans of skiers scattering southward. Those who remain smile easily, as if digesting the sweet secret of their accomplishment, as eager to spill race details as they are thankful for people who understand them.

Invariably, a small movement forms among the lingering skiers, who gain gentility with nightfall, and some of us agree to meet the next morning on the frozen lake for a Sunday glide. From the lonely, halogen-lit asphalt of the Central Park gerbil wheel, it is childish delight to ski among able brethren in a hardwood forest, for once not worried about race tactics. We hash over the prior day’s travails, questioning the minute decisions that mete out our limited stores of energy. We understand each other’s vulnerabilities; we respect each other’s work. On the downhills, I notice my skis don’t glide as well as theirs. This time, I don’t worry about the train. I let them slip away.

Works Cited:

Frado, Chris. “Re: Numbers of Cross Country Skiers in the US.” Message to the author. 1 Mar. 2014. E-mail.

“History.” Birkie.com. American Birkebeiner. 2014. Web. 2 Mar. 2014.

Ryland, Julie. “Cross-Country Skiing: Norwegian’s Favorite Sport. ”The Norway Post. The Norway Post. 13 Nov. 2011. Web. 15 Mar. 2014.

Sandbakk, Oyvind and Hans-Christer Holmberg, “A Reappraisal of Success Factors for Olympic Cross-Country Skiing.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 9 (2014): 117-21. Web. 2 Mar 2014.

Sinnott, Mikey. “Re: Mass Starts and Trains.” Message to the author. 28 Feb. 2014. E-mail.

Images:

Kochon, Alex, “Babikov the Canadian ‘Bulldog’ to Race Fourth American Birkebeiner,” Fasterskiercom. 2013. 18 Feb. 2016. JPEG.

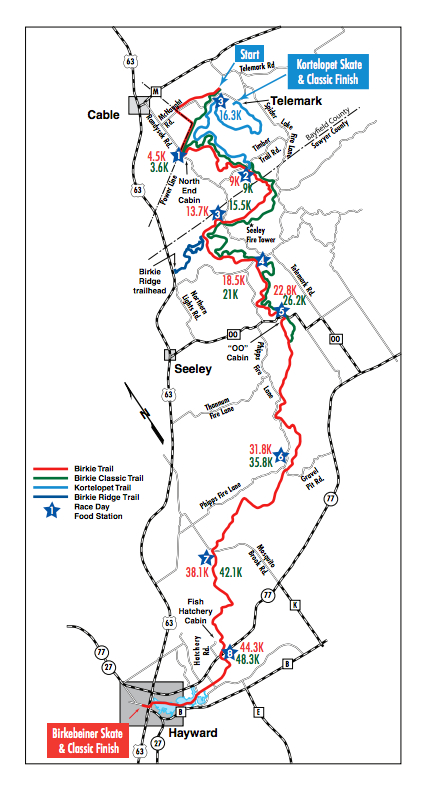

“American Birkebeiner, Birkebeiner Classic & Kortelopet Trails, Map.” Birkie.com. American Birkebeiner. 2014. Web. 2 Mar. 2014. JPEG.

Skinnyski.com. “2012 American Birkebeiner—Midway Leaders.” Online Video Clip. YouTube. 26 Feb. 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2014.