Art History and Access: The catalogue raisonné as Collaborative Research Site

Elizabeth Alice Honig

published July 2014

For the age of new media, janbrueghel.net provides a web-based model to replace the traditionally published catalogue raisonné. As an intervention in the discipline of art history, the site offers crowd-sourcing of catalog data and ways to post opinions on the works of an artist whose oeuvre is particularly difficult to delimit. The site redefines the oeuvre catalog itself as an open-ended, flexible, collaborative enterprise. Finally, the site exists as an innovative way of making a reliable (if indefinite) catalog of the artist’s work available to both the general and the scholarly public. It is an attempt to move one of the most fundamental and conservative forms of art historical scholarship into a new, more dynamic and interactive format made possible by the digital age.

A catalogue raisonné is a compendium of every painting, drawing, print and/or sculpture that a given artist has produced. Such publications sort the wheat from the chaff, original works from derivatives and forgeries, so that all further art historical scholarship is premised (at whatever remove) on access to a trustworthy catalogue raisonné. Art historians have an intense love-hate relationship with their catalogs. Catalogs are condemned as involving outmoded connoisseurship rather than critical thinking, and as endowing the eye of a single individual with inordinate authority. They are too often influenced or corrupted by the demands of the art market; they become outdated as soon as the next expert produces a new catalog; and yet they are very costly to publish and to purchase.

Cataloging the work of the Flemish painter Jan Brueghel (1568/9-1625) has always been particularly challenging. His body of work is uniquely messy: thousands of paintings, hanging in museums and private collections all over the globe, have some claim to be associated with his workshop. Some pictures were produced with the input of independent collaborators, including major masters like Peter Paul Rubens, while others were executed in part or entirely by anonymous paid assistants working within the studio. The same composition may exist in a dozen versions of different sizes in different materials from different dates and executed by different individuals. Jan and his artist-brother Pieter the Younger used visual materials from the estate of their father, the famous painter Pieter Bruegel, producing both exact copies and variants of his work; Jan’s own son would do the same thing after his father's death. Bruegel/Brueghel images can thus be thought of as a massive and entangled family tree, stretching over generations, with works connected to one another by varying degrees of intermarriage, imitation, and inspiration.

Two catalogs of Jan Brueghel’s paintings have been published, both by the same author, Klaus Ertz. Ertz owns his own publishing company and supports himself by authenticating pictures for art dealers; he has also cataloged the works of Jan’s brother and his son. Because of his dependence on the art market, Ertz has insisted that every image can be firmly attributed to a single hand, and that none were made by assistants. It is therefore generally accepted that his attributions are extremely unreliable; nonetheless, no further work can be done on this painter without using and referencing his books. The first catalog, published in 1979, now costs over $1200 as a used book; the revised and updated four-volume version, although underwritten by the dealers whose works Ertz authenticates, costs about the same amount. Therefore, fewer than forty libraries in the United States own both editions of the catalog, even though both are needed for research purposes. Not a single library in the UK owns both. And these are rich countries: scholars in Eastern Europe, or South America, are almost completely cut off from these basic research tools.

The published Brueghel catalogs typify the problems that bedevil this type of scholarship. These books are extraordinarily expensive to produce. Hundreds of (copyrighted) illustrations, many in color, printed on heavy paper to optimize hue and resolution, and sometimes running to several volumes–an academic press will spend between a $150,000 and $500,000 to produce such a book. This is why they in turn charge buyers hundreds, even thousands of dollars. Since most catalogs become outdated fairly soon, as more objects by and documentation on the artist are discovered and opinions on attribution shift, publishers usually produce fairly small print runs, and the books quickly become rarities. For example, according to recent information from artbooks.com and bookfinder.com, the classic 33-volume catalog of Picasso’s work, published from 1942-1978, costs $50,000 for a library to purchase today. To make up their costs, independent publishers accept subventions from dealers or private owners who know that the value of their property will increase by being included as an A-level attribution in a catalogue raisonné. This obviously corrupts the credibility of the catalog, but it has become an almost expected part of the broad economy of art history.

Although art history is still very much a paper-based field, the catalogue raisonné is a type of material that would benefit from being housed online. The move would decrease costs, broaden access, and allow for constant updating as new information emerges and opinions change. Websites on some artists already exist: for example, essentialvermeer.com is a masterful compendium by a dedicated individual, Jonathan Janson, that covers every aspect of the artist’s work and has taken over a decade of hard work to construct. Picasso.shsu.edu is a limited access, copyrighted, scholarly site that catalogs Picasso’s almost unimaginably large oeuvre and is again the work of a single scholar. Already, we see several problems here: while the production of books was enabled and subsidized by the larger publishing industry, constructing a scholarly website presents a significant financial challenge and is generally a lonely task. It is also one that wins its architect little career advancement, for most universities barely recognize the existence of online, non-peer-reviewed work.

Some foundations established by individual modern artists sponsor online catalogs. For example, Arshile Gorky’s foundation has produced a particularly good open-access catalog. Other foundations use their websites as a place to invite collectors or dealers with a work by their artist to submit information about that work for inclusion in a published catalog: Andy Warhol, Hans Hofmann, Salvador Dali, Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Mitchell, and Francis Bacon are major artists whose catalogs are open to online submission. Some artists’ works are cataloged online directly by the galleries who have dealt in those works. Thus, the internet has begun to open the catalogue raisonné to a type of crowd-sourcing (which is a good thing) and has increased its intersection with the art market (which is not).

janbrueghel.net takes the online catalogue raisonné several steps further.

It takes advantage of collaboration and crowdsourcing, while also maintaining a level of academic integrity that will make it useful to scholars worldwide who cannot access the costly published catalogs. Its audiences are multiple. The Hungarian high school student looking for information about a picture in a local museum; the curator in Santiago de Chile wanting to organize a (virtual) exhibition and needing to track down works related to one they own; the art dealer or collector confronted with a picture they think might be by Jan Brueghel; the academic scholar doing a study involving one or many works by the artist; the tourist wanting to know what works by Brueghel she can see on a visit to Rome: all can access the catalog and find the material they need.

While access to the site’s data is freely available, janbrueghel.net also serves as a research portal for a second level of users: academic scholars, museum curators, and also art dealers. After registering, they can then add information they may have on artworks that they own or are in the collection that they curate. They can make their opinions known about the authenticity of a work and post material such as curatorial archives, micro-photographs, or infrared results, supporting new ideas and allowing new lines of scholarly knowledge to germinate.

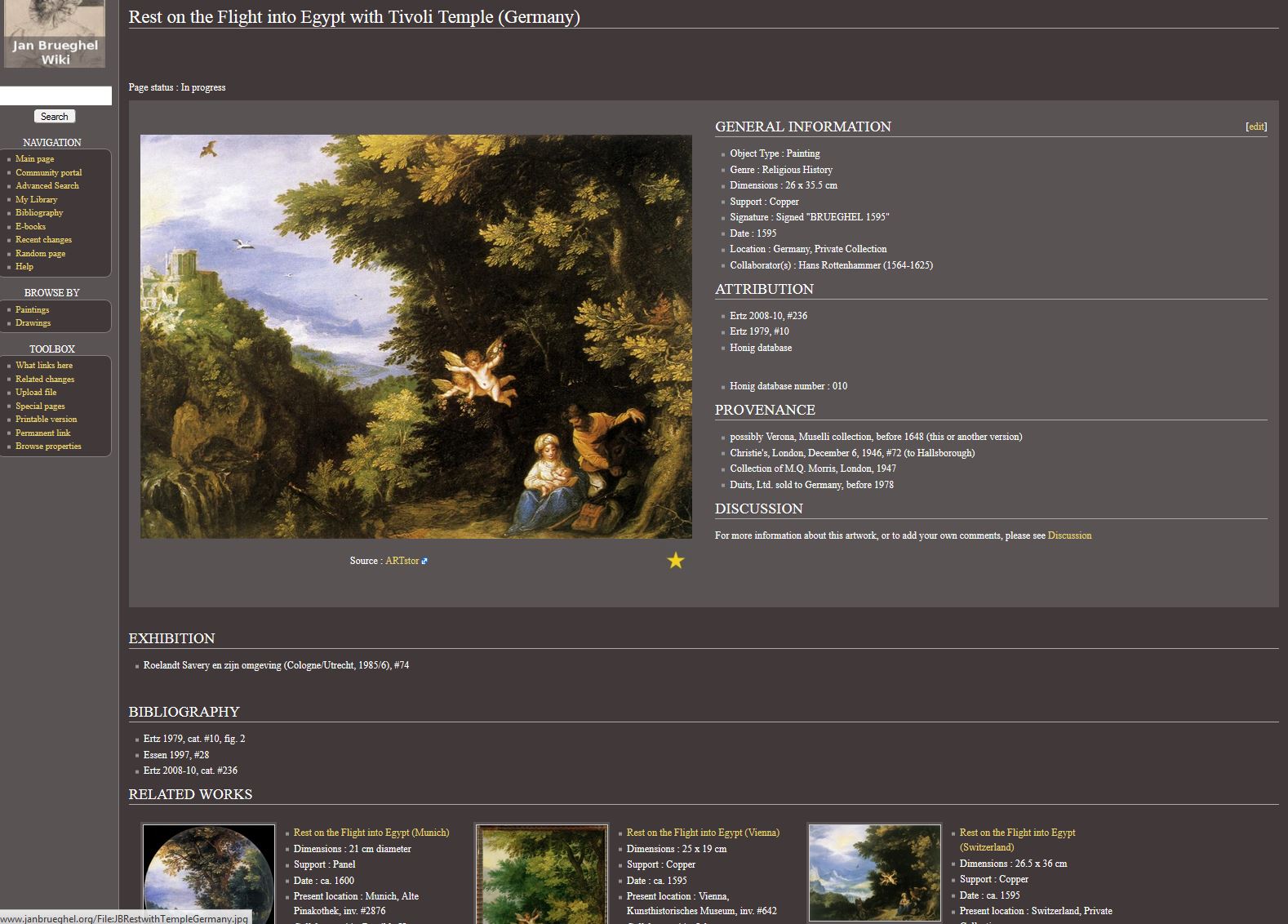

The basic catalogue raisonné has been created in a wiki format, using mediawiki with a semantic extension to enable advanced search functions. We chose this familiar format to encourage contributions by people who are not particularly computer literate. Each object—whether drawing, painting, or print—has a page that includes basic physical data about the work, provenance, bibliography, an image, and “minis” of all the further paintings and drawings that are visually related to the main object.

Each page also has a discussion back-page where registered users contribute their ideas and materials.

In this system, no individual connoisseurial eye is privileged over other experts. Shifts in opinion based on new information can be registered instantly, and knowledge about Brueghel’s work is seen not as a static body of data but as formed through a continuous dialogue between many interested parties.

Computer programmers Charles Henderson and Angela Hong have developed the Image Investigation Tool (IIT) that is being integrated into the website. Registered users first create a “library” of images they wish to study and then launch the IIT using their library images. The IIT enables the user to crop a section out of one picture, create a transparency of that detail, and, if necessary, flip or tilt it, and overlay it on the other work. It also calculates the relative size of each detail.

We can thus begin to judge whether a pattern drawing was exactly repeated or resized, whether it was copied mechanically or manually, or whether one painting was copied visually from another without the use of a pattern. The information gleaned from such investigations will eventually enable users to map out sub-sections of the imagery generated by the Brueg(h)el family.

Our site already comprises a fairly high-volume data set. We have about 800 pages, consisting of perhaps 75% of all the paintings and drawings attributed to Jan Brueghel and his workshop. As we move on to add further members of the family to the website, this number will increase significantly until we have several thousand discrete pages. Over the coming year, we will begin a parallel wiki-based catalog of the work of Jan’s father, Pieter Bruegel. Including the famous Pieter will greatly increase our online presence and will attract a different, less scholarly type of visitor. Therefore, we will add new capabilities and informational areas into an umbrella site: brueghelfamily.net. This site will include a scale gallery, constructed with the help of the app ArtAuthority, allowing users to view images as if framed and displayed on a wall at actual scale, with human figures for comparison. A bibliography will provide links to online sources or to Amazon for book purchases, an index of works by location will link to museum websites, and short texts will give information on each artist and their patrons, publishers, and collaborators.

When complete, the site-cluster will contain ever-expanding fields of data on a number of related artists. Those fields can be differently searched, grouped, and utilized by users all over the world who come to us with a multitude of different agendas, questions, and backgrounds. Unlike most published works of scholarship, our website can be flexible enough to speak to audiences within and outside of the scholarly world. Because it does not attempt to synthesize and interpret all of its data as a single-authored text would do, it allows for continual collaborative idea-making.

Despite its vanguard nature, there are some limitations to imagining janbrueghel.net as a model for future digital scholarship in art history. First, I am not sure how many researchers will choose to share a database in this way, inviting others to use it and to contribute to it and correct it in such a public manner. Most academics still want control over their own materials. Until there is some mechanism for the assessment and recognition of digital and collaborative open source ventures within the academic humanities, the model of the multi-contributor open-investigation website will not be very viable.

Image copyright is another difficult point for digital art history. Our site was given hundreds of images of works in private collections by two major photo archives, the RKD in The Hague and the Rubenianum in Antwerp. For works owned by museums, the situation is more difficult. Some museums now allow free use of digital images of their works, but others have licensed their images to commercial vendors. These vendors try to prevent works from appearing online on open access sites so that they can charge significant amounts for each user’s access. I believe that the pressure from freely-available image sources will eventually undercut museums’ and galleries’ ability to control the use of their artworks. But as of now, a website like ours sometimes skirts the edge of legality.

A further challenge for any digital project is funding and sustainability in the grey zone between scholarship and public access. A complex website costs a lot, but not as much as the big NEH grants that go to well-established groups and institutions. Individuals with moderate needs might find start-up funds, but a steady funding stream for continued maintenance and development is hard to ensure. You can try to develop a business model based on revenue generation, but if your site becomes subscription-only, it loses the key benefit of easy availability to scholars outside of wealthy Western libraries. Moreover, most scholars are not eager to run a small business in order to distribute their research.

And that is the final problem: who will assess, preserve, maintain, or archive even the most carefully constructed sites? A book is forever; a website disappears when its author stops paying for the domain name and hosting service. Gradually, institutional structures are developing to play these roles. I hope that scholarly publishers and professional organizations, such as the MLA and the CAA, will also step in, to some degree, to take on functions of assessment, publicity, and archiving. What is certain is that until the scholarly world treats the digital humanities with as much seriousness as humanism on paper, and invests in ways to maintain work in digital spaces, that work will be more ephemeral than any intellectual endeavor has been since the invention of the papyrus scroll.

Works Cited

Ertz, Klaus. Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568-1625): Die Gemälde mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog. Cologne: DuMont, 1979.

Ertz, Klaus, and Christa Nitze-Ertz. Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568-1625). Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde. Band I: Landschaften mit profanen Themen. Vol. 1. Lingen: Luca Verlag, 2008-10.