Memory and Identity in the Emotive Map of Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

by Jytte Holmqvist

published November 2014

1. Introduction:

The focus of this article is Alain Resnais’ representation of collective and individual memory and identity in Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959). The film is based on Marguerite Duras’ script from 1958 and remains faithful to this original text. With partial reference to Giuliana Bruno’s views on imaginary cities and urban cartography, the screened urban space will here be read as an emotive map in which the individual love story between the protagonists unfolds against the backdrop of their almost equally intimate relationship with the historically abused city of Hiroshima. This, in Bruno’s words helps create an affective “map of love” (243) or a “body-city on a tender map” (242). Discourses on memory and forgetting, individual and collective memory will also frame a filmic analysis where Paul Ricoeur is given particular theoretical attention. In a film partly dealing with the traumas of the 1945 atomic bomb and its aftermath, Resnais visually and narratively juxtaposes wartime Hiroshima and the city twelve years after the event: as stated in Duras’ original filmscript, “[t]he time is summer, 1957-August-at Hiroshima” (8). In doing so, he unveils the many layers of historical unease that dwell behind Hiroshima’s currently peaceful condition. The paper highlights the fluid relationship between the protagonists and their environment, as well as the semi-documentary aspects of a film that establishes an effective dialogue between past and present.

2. Cinematic plot and setting:

Resnais’ positively acclaimed French New Wave film (first shown at the Cannes Film Festival in 1959 and also nominated for an Oscar that year) effectively and purposefully interweaves real documentary footage of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August, 1945, with images of Post-war Hiroshima and two lovers’ narrated recollections of war that serve to humanize the filmic text. This cinematic tour de force has captivated viewers and critics alike who have written extensively on a film that explores the abstract landscape of individual and collective memory and identity (thematically, the film shares commonalities with the also historically concerned Night and Fog (1955), Last Year at Marienbad (1961) and Muriel, or The Time of Return, from 1963). Hiroshima Mon Amour also talks of the fear of forgetting yet the simultaneous impossibility of forgetting individual and national traumas. As mentioned, here real photographic evidence and footage from the atomic bomb are interspersed with a fictive, personal discourse, and in her edited volume from 2010 Susannah Radstone explains that:

[i]n […] Hiroshima Mon Amour […] art and avant-garde cinema’s abiding fascination with memory expresses itself through relatively immobile camerawork, lengthy, photograph-like shots, and brief flashback sequences evocative of involuntary memory. (328)

In narrative focus is an anonymous Japanese architect (played by Eiji Okada) and an equally anonymous screened French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) whose modern love affair unfolds in 1957 Hiroshima. The lengthy dialogues between the man and the woman solely referred to as elle and lui constitute the driving force behind a film where the main focus is on character development rather than external action. The words uttered between the protagonists render them more complete and complex and through their conversation a dialogue is also established with Hiroshima itself. The city not only provides the setting for their affectionate encounter but it is conferred almost human value. As noted by Bruno, in the “composite map” that is Hiroshima Mon Amour:

[w]ith cross-cutting, reconnecting emotional places, we can now see this city, the imagined geography of her tender mapping, as the condensed, displaced city of filmic montage. Made to the measure of love, it is a cinematic creature—a cine city. (244)

In this Japanese cine city, past and present constitute two interrelated aspects of the same filmic montage. The “now” and “then” are brought into dialogue, as are the protagonists who are linked not only amorously but also cross-culturally. They are conversationalists dwelling on aspects of war and peace in a city that embraces a new identity in the Post-war era. In doing so, the filmic characters explore also their own pasts prior to their Japanese encounter. When their individual fates and backgrounds finally converge within the context of a multi-layered, modern Hiroshima that remains conscious of its comparatively recent belligerent past, different cultures, ethnicities and value systems are symbolically interwoven.

A film which in Rosamund Davies’ view “problematizes memory, history and indeed representation itself” (151) generally steers clear of political commentaries in the sense that a definite standpoint for or against any particular nation is never taken. Rather, the urban space comes to the narrative forefront and becomes a third, less conventional protagonist. Resnais’ juxtapositioning of historical evidence reflecting the horrors of war and the diametrically opposed love story that ultimately adds a sense of hope to the film becomes further effective when the past, from Ricoeur’s perspective, “persists in the present” (390). This reminds of John Ellis’ notion of a “presence-yet-absence that can be called the ‘photo effect’” (38). Specifically, in the film Japanese citizens protest against nuclear weapons and warfare in a now peaceful Hiroshima. This helps anchor the narrative in the recent past while at the same time the cartographic flashbacks also contrast with images from the present. Resnais’ archival cinematic map is thus alternated by scenes from a modern city propelled into a global future.

3. A cartographic reading of Hiroshima Mon Amour and its narrative treatment of memory, loss and altered identities:

Bruno’s concept of an “emotional cartography—a site of ‘transport’” (67) can be applied to the film in the sense that it establishes not only a cultural connection between the protagonists, which is partly aided by the woman’s willingness to understand Hiroshima now and then. But at the same time these protagonists represent east versus west and share a victimhood through their respective countries’ experiences of war. Their ongoing physical and verbal interaction helps bridge their cultural differences and may be read as a screened attempt to instil hope in the viewer with regard to people and nations coming to terms with the haunting memories of the Hiroshima bombing. In the film, an additional subplot (expanded on later in this article) that develops in the French city of Nevers on the banks of the River Loire, becomes yet another way for Duras and Resnais to narratively interweave history with memory, or to historicize memory in a manner theorised on by Ricoeur (389).

Still, it appears Duras’ and Resnais’ joint aim is for a healing process to take place both on an individual and (inter)national level. This attitude seems to correspond with Katharine Hodgkin’s and Susannah Radstone’s view that:

memory is not individual but cultural: memory, though we may experience it as private and internal, draws on countless scraps and bits of knowledge and information from the surrounding culture, and is inserted into larger cultural narratives. (5)

Indeed, it can generally be argued that not until people dare face a traumatic national past can they deal more effectively with the present and can a country’s (and a city’s) transition into the future become smoother. Rather than being detached or separable from the past, the present is a product of this past, as are those dwelling in the present. In his analysis of La mémoire, l’histoire, l’oubli, Abdelmajid Hannoum summarises Ricoeur’s ideas by writing that, “the representation of the past is […] the issue of the presence of something absent” (124). Similarly, Keith Ansell-Pearson argues that:

nothing is less than the present moment, if we understand by this the indivisible limit that separates or divides the past from the future. (62)

A spatial reading of Resnais’ film allows for an urban comprehension of Hiroshima as a city whose present is linked to its past and where the future is in turn connected to both past and present. Such a narrative fusion of different time periods adds depth to a film which appears to propose that not until the past is properly acknowledged can the present be better understood and processed.

Significantly as well, apart from historically mapping the urban space, Resnais also creates a tender imagery not only through his visual portrayal of the intimate couple in focus but also in terms of how they relate to the Japanese cityscape—and which is in an almost organic manner (the lack of a proper name for these characters further seems to facilitate their organic relationship with the city).

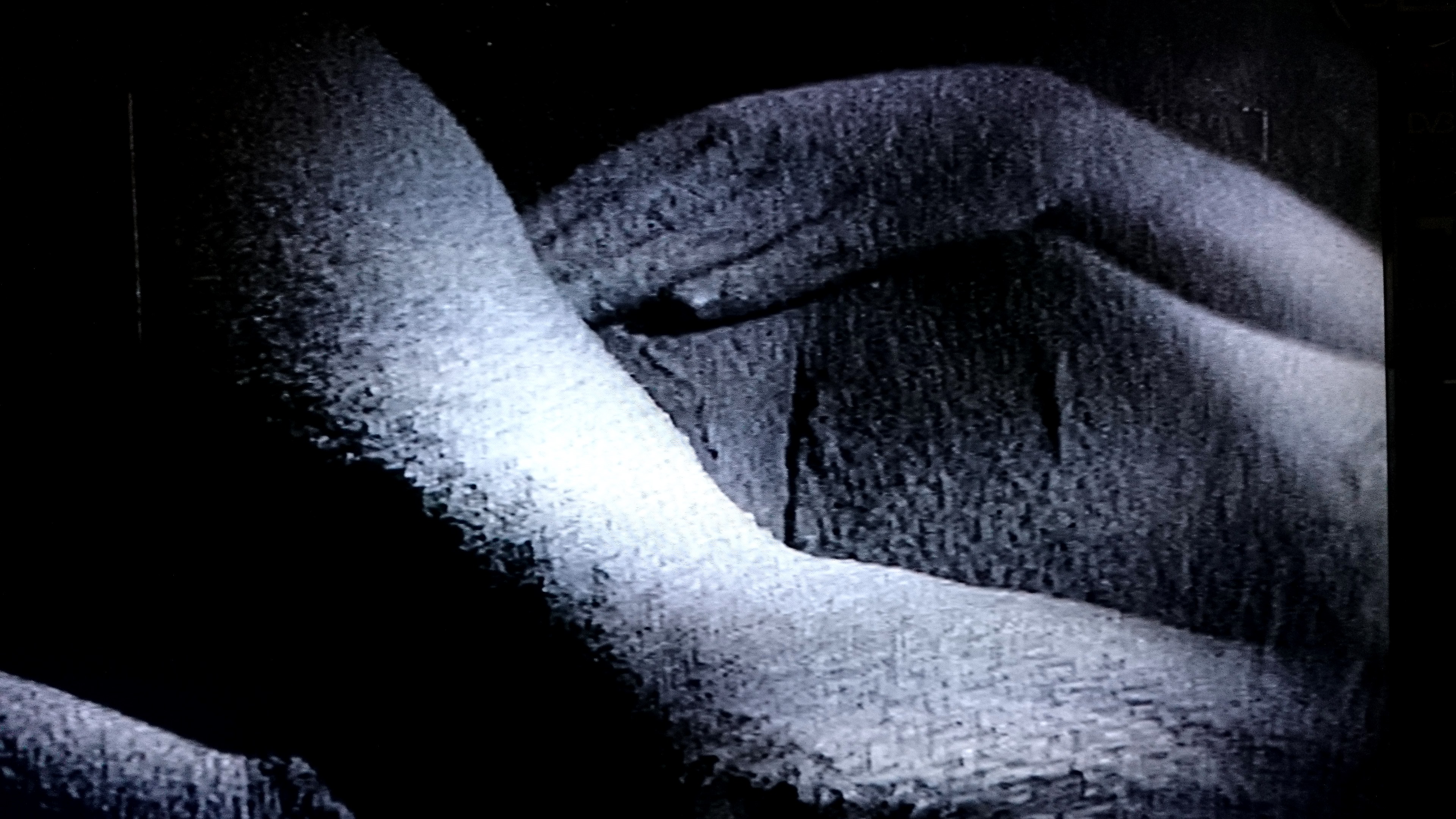

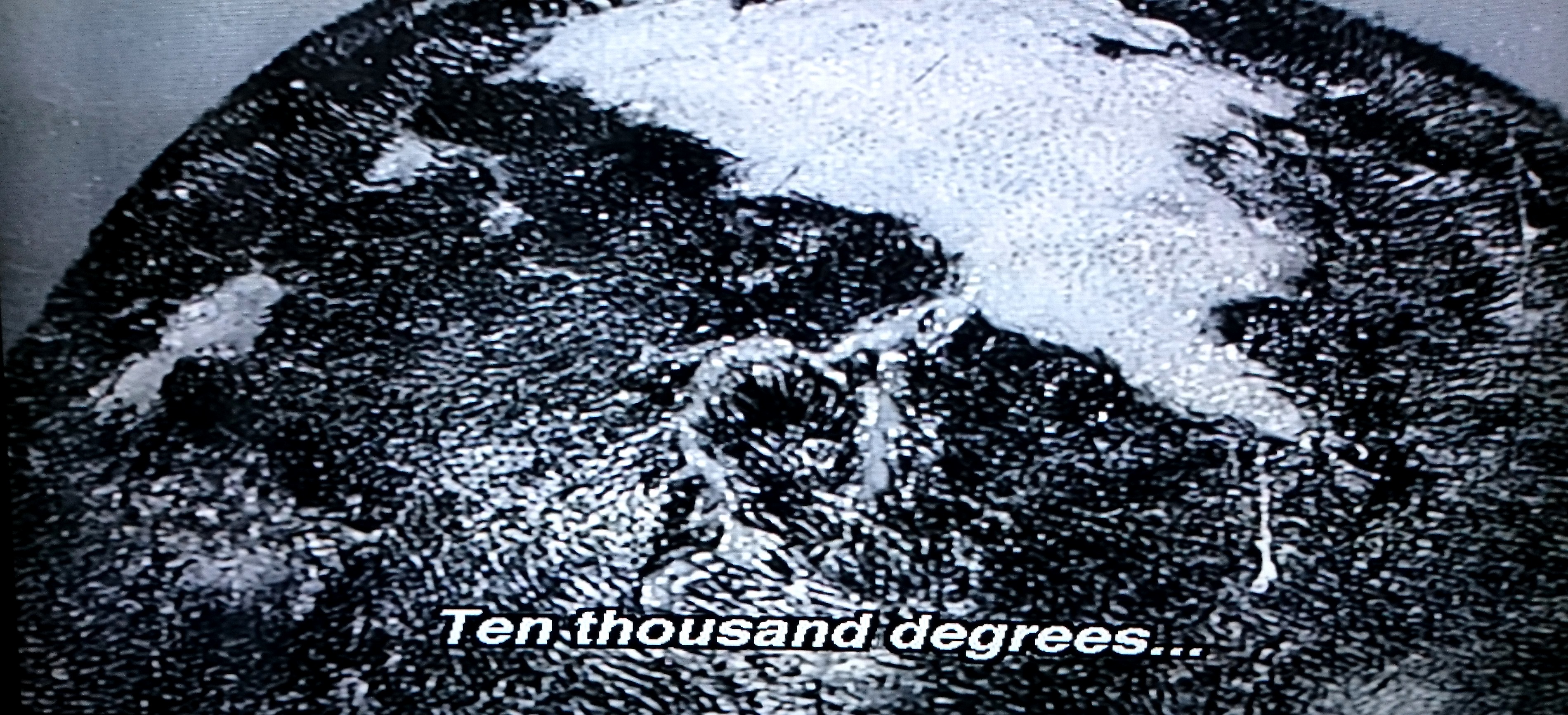

The viewer of Hiroshima Mon Amour is initially presented a series of images that form a prelude to the subsequent narrative discourse between the protagonists. The first shot is a grainy black and white close-up of two naked bodies intertwined in a close embrace, and seemingly covered in dust. The visual lingering on these ashen bodies is effectively paralleled with documentary footage and partly reconstructed images of human sufferers of the Hiroshima atomic bombing: corpses, distorted bodies of victims and survivors, children and adults unsteadily navigating themselves through a sea of human suffering... Bruno has called these juxtaposed images part of a “psychoanalytic tour” which “spirals backward.” In her words, the film:

begins and ends with a woman’s geography. First, we see her body embracing the Japanese architect, whose image has been superimposed on a scene that is the body of the city of Hiroshima […] The journey of love takes shape as we travel the city streets [...] [and finally] Nevers and Hiroshima begin to merge on the map of love. (243)

The subsequent, almost poetic yet also rather one-sided, dialogue between the lovers (who are still facially unidentifiable) is initially one of alternating acceptance and denial. Thus, while elle embraces the memories of the Japanese-American war and her own indirect experience of it through the media representation of the atomic bomb and its crippling aftermath, lui denies that she had anything to do with the city: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing.” In response to the woman’s contrasting claim that she has “always wept over the fate of Hiroshima. Always,” the Japanese retorts rhetorically: ”What did you have to weep about?” The man’s initial reluctance to accept her voiced sympathy for the city and its painful past can be read as his attempt, simultaneously, to repress this past and to discard the second-hand account of the war, by a non-Japanese woman. In their dialogues, he does not linger on the topic of his dead relatives perishing in the 1945 atomic explosion. And yet, analysing the film from a feminine-matrixial perspective, Kyoko Gardiner argues that lui is indeed “repeatedly in touch with his lost family members who are still, while dead, always around him as partial-subjects, as his intimate non-I’(s)” (255). Thus, Gardiner speaks of the encounter between the dead and the lingering semi- or surreal existence of those “left-behind” in the very minds of the people who still remember them; the encounter, thus, between the “no-longer, and the still” (255).

Again with regard to elle’s opening discourse on Hiroshima, she finally stresses that she, too, knows what it is like to forget: “Like you, I am endowed with memory. I know what it is to forget.” In a slightly contradictory fashion they thus remember “in order to forget”, as argued by Inez Hedges (293). The act of trying to forget can in the case of the Japanese man be seen as a defence mechanism. By initially not addressing the past, he denies the French outsider “access” to the Japanese people’s collective mourning of Hiroshima. At the same time, this attitude also allows him to himself close the door on a past which involves the pain of losing his family to war. Instead, he can now more readily step into a new era and the woman can serve as a vehicle into this future. Gardiner considers the Japanese man a modernist in his initial responses to his female companion. Thus, when lui indirectly uses this lover and fellow conversationalist as a symbolic passageway to the future:

he builds a new landscape: he tears down the past and plants the future […] For him, the French woman is not just [an] object of his desire but also a possible passage into the future, the Europe, the centre. (257)

Not only does elle provide lui with a new future in which he can gaze outward and may be able to distance himself from the memories haunting his nation. But thanks to his corresponding interest in the woman’s own recollections of war in occupied France, she, too, can move on and heal after a mentally scarring experience in her hometown of Nevers prior to its liberation in September 1944. More specifically, her personal trauma involves the memory of a relationship with a German soldier at the end of the French occupation. The soldier was shot dead immediately before the town was set free, after which she was accused of having collaborated with the enemy and was publically ostracised by her fellow citizens. The Kafkaesque Nevers episode and elle’s lingering sadness with regard to this recent past has, on a number of occasions, been interpreted from a feminist perspective. Sarah French thus calls the woman’s repeated recollections a “narcissistic obsession with mourning”(8) and she draws from Kristeva’s idea of sadness as “the most archaic expression of an unsymbolizable, unnameable narcissistic wound” (12). In more general terms, Ricoeur asserts that:

[t]he work of mourning is the cost of the work of remembering, but the work of remembering is the benefit of the work of mourning. (72)

A Deleuzian reading of the screened Nevers episode has also been provided by Kristyn Gorton. And Doris Enright-Clark Shoukri argues that elle’s traumatic French episode:

defines her, and to corroborate her existence, she must communicate it. Only in Hiroshima, in the enormity of its suffering while the world rejoiced, can she find an objective correlative for her own life. (319)

In the film, elle’s sharing of this experience with her Japanese lover grants him access to her past and simultaneously he gains an insight into her mind (“I can only begin to know you. And out of the thousands of things in your life, I choose Nevers”). He also becomes instrumental in her healing process, starting from the very moment in which she first recounts what happened to her prior to her arrival in Hiroshima. Lui encourages her to fully address these traumatic memories and symbolically he also becomes a stand-in for the dead German when he takes on the role of this previous lover in an enacted, therapeutic dialogue with the woman. The almost trancelike commentaries on her part mentally bring them both back to the damp cellar in Nevers where she was locked up as a punishment for her 1944 love affair. As highlighted earlier, the memory of an event in the past is thus called forth in the present in a manner that abides by what Ricoeur calls an “ambition” or “claim” tied to memory: “that of being faithful to the past” (21). The Japanese can subsequently form a more complete picture of his lover:

[i]t was there, as I understand it, that I almost lost you, that I risked never, ever meeting you. It was there, as I understand it, that you must have started to become what you still are today.

Consequently, an individual memory is turned into a shared experience whereby the healing process can begin. With this, a double victory has been achieved, also that of listening “to the voice of the unforgetting memory”, as Ricoeur puts it (501). And in a comment inspired by Augustine, Ricoeur further asserts that ”recognizing something remembered is experienced as a victory over forgetfulness” (99).

Memory’s victory over forgetting is in the film not only represented narratively and visually through the protagonists’ cathartic dialogues that shed light on past events brought forth in the present (again, elle’s voiced Nevers experience serves as a confession effortlessly received by her non-judgmental fellow conversationalist). But also, this victory extends to the screened refusal- on both an individual and collective level- to forget Hiroshima’s own painful past through an organized peace rally through the sunny urban streets where the city and its people unite against violence. This collective protest reflects Jay Winter’s observation that:

[s]ites of memory vanish, to be sure, but they can be conjured up again when people decide once again to mark the moment they commemorate. (324)

The communal peace celebrations are further underscored by elle’s participation in an anti-war movie shot on location in Hiroshima (a film within a film which parallels the collaborative effort between France and Japan in the production of Resnais’ movie). Commenting on the theme and chosen setting for this film, the woman finds the choice of Hiroshima obvious: “A film about peace. What else would we be making in Hiroshima?” When asked if this is a French production, she stresses that it is “international” rather than French or pertaining to any other nationality. This foreign interest in equalling the modern city of Hiroshima with “peace” is also echoed in the later comment by her modernised, French-speaking lover, with regard to both national and foreign feelings of euphoria during the aforementioned liberation of France at the end of the Second World War:

The whole world rejoiced. You rejoiced with the whole world. It was a lovely summer’s day in France that day. Or so I’ve heard.

The woman confirms: “It was lovely, yes.” Interestingly, at this stage of the plot, the man has become more vocal. However, rather than voicing his personal opinions on the war and his own participation in it (his time serving as a soldier is merely mentioned in passing) it seems he encourages an alternative female discourse. Curiously too, it is he, rather than she, who falls deeply in love: “You very much make me want to fall in love.” She rather holds back and sees their affectuous encounter (as Gardiner would have it in her article where these words are being used) and their role in it as “ships that pass in the night.” And yet, their brief encounter has helped them both come to terms with past, present and future: their own as well as that of Hiroshima. The city refuses to forget its victims of war while at the same time it celebrates the possibility of enjoying a situation of national peace and tranquillity. As a result, a new identity on a number of levels can also be embraced.

In a powerful scene towards the end of the film and prior to her (unscreened) departure from Hiroshima, elle confronts the memory of her dead German lover and in doing so experiences a symbolic moment of catharsis when she finally confesses to him (in memoriam) that “I betrayed you tonight with that stranger. I told our story. It could be told, you see.” By having shared her “sad little novelette story” (though ironic, this description is not devoid of melancholia) with another man she can finally come to terms with her past. Thus, her haunting memories are finally lighter to carry. This scene conforms to Freudian theories on dialogue as an important psychoanalytical method. As Richard Terdiman summarises with regard to Freud: “in psychoanalysis, recollection is not just individual; it involves a system of two people working together” (94).

In the film, elle’s affectionate encounters ultimately become experiences to draw on and turn into lighter memories rather than mainly negative or sorrowful ones. As a result, both she and lui are seemingly able to constructively move on with their separate lives in different countries. The final fusion of individual and national identities in the protagonists’ mutual naming or “identification” of each other can again be read as a way for them to come to terms with the past as well as with their countries or cities of origin: “Hi-ro-shi-ma. Hiroshima…it’s your name.” “That’s my name, yes. Your name is Nevers. Nevers is in France.” An almost symbiotic relationship between the characters and the urban space has been achieved.

In Bruno's words:

a lover’s journey has many paths. Tracing them, the narrative itinerary of Hiroshima mon amour enacts a filmic game of tender mapping. A loved body turns into the woman’s own geography. It marks her place of origin and her transits through cities, charting her motion from town to town, from country to country. (243)

4. Conclusion:

Hiroshima Mon Amour thus ends on a positive note, as by apparently identifying with their respective nations, the protagonists appear to have symbolically made peace with the past. By engaging in a mutual healing process through which traumatic events are openly addressed and reflected upon, these individuals have ultimately grown stronger and also closer to their own nations. It is such individual strength and re-identification with one’s homeland—something which Bruno interprets as a “psychogeographic” (277) space—that can foster peace (in Japan and the city of Hiroshima in the case analysed) and stimulate rewarding international interaction and collaboration rather than destruction and subsequent alienation between people—and between citizens and their urban habitat.

Works Cited

Ansell-Pearson, Keith. 4. “Bergson on Memory.” Memory: History, Theories, Debates. Ed. Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz. New York: Fordham UP, 2010. 61-76. Print.

Bruno, Giuliana. Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film. New York: Verso, 2002. Print.

Davies, Rosamund. “Screenwriting strategies in Marguerite Duras's script for Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1960).” Journal of Screenwriting 1.1 (2010): 149-73. Print.

Duras, Marguerite. Hiroshima Mon Amour. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1961 (1960). Print.

Ellis, John. Visible fictions. Cinema: television: video. London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982. Print.

Enright-Clark Shoukri, Doris. “The Nature of Being in Woolf and Duras.” Contemporary Literature 12.3 (1971): 317-28. Print.

French, Sarah. “From History to Memory: Alan Resnais' and Marguerite Duras' Hiroshima mon amour.” emaj 3 (2008): 1-13. Print.

Gardiner, Kyoko. “Affectuous Encounters: An Ettingerian reading of feminine-matrixial encounters in Duras’/ Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour.” PostGender: Gender, Sexuality and Performativity in Japanese Culture. Ed. Ayelet Zohar. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2009. 251-275. Print.

Gorton, Kristyn. “Desire, Duras, and melancholia: theorizing desire after the ‘affective turn’.” feminist review 89 (2008): 16-33. Print.

Hannoum, Abdelmajid. “Paul Ricoeur on Memory.” Theory, Culture Society 22.123 (2005): 123-37. Print.

Hedges, Inez. “Form and Meaning in the French Film, II: Narration and Point of View.” The French Review 54.2 (1980): 288-98. Print.

Hiroshima Mon Amour. Directed by Alain Resnais. Distributed by Argos Films, Umbrella Entertainment and Shock, 2008 (1959). DVD.

Hodgkin, Katharine, and Susannah Radstone, ed. Contested Pasts: The Politics of Memory. London and New York: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Kristeva, Julia. Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia. New York and Oxford: Columbia UP, 1989. Print.

Radstone, Susannah. “Cinema and Memory.” Memory: History, Theories, Debates. Ed., Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz. New York: Fordham UP, 2010. 325-342. Print.

Ricoeur, Paul. Memory, History, Forgetting. Chicago and London: The U of Chicago P, 2004. Print.

Terdiman, Richard. “Memory in Freud.” Memory: History, Theories, Debates. Ed. Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz. New York: Fordham UP, 2010. 93-108. Print.

Winter, Jay. “Sites of Memory.” Memory: History, Theories, Debates. Ed. Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz. New York: Fordham UP, 2010. 312-324. Print.