NANO Special Issue Introduction to Cartography and Narratives

by Matthew Bissen and Laurene Vaughan

published November 2014

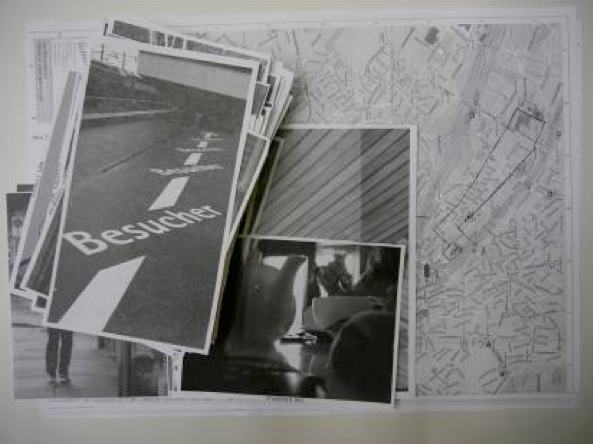

This special issue of NANO is the outcome of a two-year collaboration between the guest editors Laurene Vaughan and Matthew Bissen and their colleagues Sebastien Caquard and William Cartwright. The idea of the edition emerged from a 2012 exploratory interdisciplinary workshop on narrative cartography held in Zurich, Switzerland. Over the three days of this workshop, artists, scientists, designers, and literary scholars interrogated and reflected on the ways that we narrate the geographic and lived cartographies through maps (Figures 1 and 2). Fundamental to the creative explorations and the critical discourse were questions such as: what is a map? How and what does a map perform as a social and cultural object? And how do different knowledge domains narrate such cartographies, and in what forms?

The outcome of this collaboration is two sister publications: NANO Issue 6, and Volume 51 (Issue 2) of The Cartographic Journal. The workshop and the sister publications have been supported by the Art and Cartography Commission of the International Cartographic Association. This commission brings together an international community of cartographers, geographers, artists, and writers who have sought through innovative collaborations—including publications, events, screenings, exhibitions, and creative works—to facilitate a critical body of scholarship on the nature and power of mapping.

To build a bridge between the two special issues on narrative cartography, the editorial team commissioned an essay by Denis Wood that is featured in both journals. As Denis Wood winds his way along the trajectory of the various submissions, this essay provides a contextual thread through the sciences, the arts, and the humanities.

The eleven notes that make up this NANO special issue explore, often in unconventional ways, the power, form, and presence (or absence) of maps as devices for narrating both personal and social landscapes. As noted by Denis Wood, there is an absence of conventional maps in the contributions and this “has precisely the effect I was hoping for, that of flattening, spreading out, smearing not only the words themselves but the concepts classically attached to them, concepts ultimately focused on the control of territory.” The territories that Wood refers to are the boundaries of place, the conventional domains of maps; but the territories that he refers to are also as much about discipline, authority, and tradition as they are about landscapes or borders.

Daniel Dorling also provides instructive context as this issue explores concepts of narrative and cartography. In Mapping: Ways of Representing the World, Dorling states “when map compilation of many different groups of people is examined in detail, cartographers can arrive at an uncomfortable conclusion: ‘it is difficult to hold unquestioning the belief that there are certain objects called maps, which most, if not all, human groups use to communicate information about the location of geographical features’ [Dorling here quotes Ben Orlove’s “The Ethnography of Maps,” 29]. The conventional view is that a picture is a map when it resembles the world in miniature and the ‘better’ it resembles the world (ie. the more accurate it is), the better a map it is” (71). This special issue navigates this “uncomfortable” notion, such that it has deliberately sought to question and challenge disciplinary authority and expectations of cartographic representative norms–it is perhaps the opening up of our capacity to narrate place and space, real and imagined, through diverse modalities of representation, which is at the core of this project.

Works Cited

Dorling, Daniel. Mapping: Ways of Representing the World, London: Longman P, 1997.

Orlove, Ben. “The Ethnography of Maps: Cultural and Social Contexts of Cartographic Representation in Peru,” Cartographica, 30(1): 1993. 29-46.

Two photographs taken by Matthew Bissen during the Workshop on Cartography & Narratives. ETH, Zurich. 6 June 2012.