Trash as Trash as Art: Reflections on the Preservation and Destruction of Waste in Artistic Practice

by Stacy Boldrick

published June 2015

On 16 June 2012 I took part with twelve other participants in the artist Michael Landy’s Workshop on Destruction, an all-day workshop included in the Hayward Gallery’s Wide Open School, a month-long series of workshops, talks, and conversations led by artists. Landy and his long-time collaborator Clive Lissaman introduced the workshop by showing short films of Jean Tinguely’s Homage to New York (1960), a large-scale kinetic sculpture set to self-destruct (or more correctly, to destroy itself) in the Museum of Modern Art’s sculpture garden, and Landy’s Break Down (2001), an art event comprising the destruction of all 7,227 of the artist’s material possessions through a systematic process of sorting, grouping, and dismantling them (both works are discussed in greater depth below). We had been asked to bring personal objects to destroy during the workshop, objects that would be attached to the framework of a base form, a large white motorized sculpture, so that the final collectively-made sculpture would serve as an homage to Tinguely’s Homage, Break Down, and Landy’s other projects—all of which had attracted many of the participants to the workshop. That an art event from 2001 could leave no original material remains and yet continue to retain its power in the public imagination seemed significant.

For the eight-hour workshop, we were instructed in advance to bring at least one object, or up to three objects:

of personal significance which will be discussed before being destroyed. The remains of all these belongings will be used to create a collective sculpture which will ultimately self-destruct as the process comes full circle. (Landy and Lissaman)

Participants selected objects that represented painful or pleasant memories, objects they simultaneously loved and hated; others were not so emotionally attached to their objects and simply wanted to dispose of them. Other participants submitted objects that they had collected over the years, or in some cases, things they had hoarded and desperately needed to expunge from their homes. One woman brought some of her dead mother’s old reading glasses, all of which she had kept because they helped her to continue to feel close to her mother after her death. Another man decided to destroy a machine he used in his work. A newly qualified teacher brought her first classwork planner, a thing of pride that she wanted to discard in order to progress beyond her training period. My wooden penguin Christmas tree decoration and a floppy disc of my PhD dissertation were two objects that represented problematic relationships, memories, and behaviors that I wanted to leave behind. We were given a wide range of tools with which we could destroy our objects, from scissors and small saws to sledgehammers, along with advice on which tools might best suit our purposes. We were told to be aware of how we were feeling when we destroyed our objects.

Once the objects had been dismantled and rendered useless as the original objects, we attached them to the base form of the self-destroying sculpture, spray painted the whole thing white—like Tinguley’s Homage—and witnessed it eventually whir itself to oblivion, after several starts and stops. Bits broke, fell off, and flew off, with Landy smashing the sculpture and its fragments from time to time with the sledgehammer to encourage its further demolition. After the event took place, Landy and Lissaman awarded all of the participants “certificates in destruction” in a mock graduation ceremony. One participant’s blog about the workshop includes links to a film clip, and the performance was televised, but no material elements survived. Trash remained trash, but the experience of making a collective self-destroying sculpture and witnessing its destruction helped me to understand the conflicted attitudes we have towards material objects and that it is possible and more useful to live without so many of them.

1. Introduction

The destruction workshop made me reflect upon one potential strategic response to consumer capitalism's incessant drive toward material excess: the transformation of discarded, unwanted, or unusable material objects into artworks that then are destroyed or self-destruct, ideally leaving behind nothing to be commodified, no further trace of waste. The process of destruction—whether it takes the form of dismantling, smashing, or blowing up—breaks up the object into fragments, abstracting it, heightening awareness of its materiality and inner workings as opposed to its objecthood. Bereft of use value and symbolic value, the object no longer exists, only matter survives. If not completely annihilated through destruction, the remains may be recycled as relics commemorating the event, or they may persist as a form of unusable waste. Slavoj Žižek addresses the problem of the utopian belief in the recycling cycle as a process that eliminates all waste with his observation that not all waste is recyclable, because the system always creates unusable waste. Žižek notes:

This is why the properly aesthetic attitude of the radical ecologist is not that of admiring or longing for a pristine nature of virgin forests and clear sky, but rather of accepting waste as such, of discovering the aesthetic potential of waste, of decay, of the inertia of rotten material that serves no purpose. (Žižek 35)

For Žižek, society’s collective faith in recycling to solve the problem of the end point of consumer capitalism—excessive consumption—should be recognized as a myth, for it denies that unusable waste always exists.

The aesthetic potential of trash is a well established subject in art practice. Recycling found objects or detritus can transform the material either into a commodified art object (which may or may not increase in value over time), or into further potentially recyclable material which can eventually become unusable waste. Waste can be reused in art works which are bought, sold, collected, and conserved, and its preservation can be considered another form of commodification. Although a great deal of artwork made from waste may inherently address the problem of excessive consumption, when waste is transformed into an image or cultural artifact that distracts the viewer from its critique, the critique can fail. The full range of forms and techniques is too vast to be reviewed here, but the practice of presenting waste as waste can be identified as central to a critique of material excess, and two approaches that attempt to escape the trap of commodification are worthy of analysis. One approach is to preserve waste, and another is to destroy it, leaving behind no trace of unusable waste to be commodified. In these notes I will explore a brief history of trash in art, consider the impact of trash presented as trash in art, and critically examine just how productive meanings and forms of it can be made today.

2. Trash as Trash in Art, and the Roles of Destruction and Decay

Trash has had a place in avant-garde art since the early twentieth century, when Marcel Duchamp introduced the idea of the readymade: any slightly modified, often discarded, manufactured object selected and displayed as an art work. From 1959, Gustav Metzger began writing manifestos for what he called “auto-destructive art,” art that resulted from its own destruction, an anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist public art form committed to social and political justice (Wilson 143). For many art historians and cultural critics, the subject of trash and art is associated with discrete art objects or installations made from waste material sourced from junk shops or the street that are transformed into works of art through their alteration and presentation in a gallery, where anything can become a commodity. In Junk: Art and the Politics of Trash (2011), Gillian Whiteley comprehensively examines a broad range of artists working with waste from the mid-1950s to today, from Arman and Bruce Conner to Mierle Laderman Ukeles and El Anatsui. Acknowledging links with ragpickers and sewage workers, she focuses on assemblage and the re-use of found objects, assessing them as inherently transgressive and political. Likewise, Harriet Hawkins (2010) considers Richard Wentworth’s work in relation to geographical space and broader political and theoretical issues. The reuse and recycling of waste materials have become conventional economical practices for artists, but once transformed into an art commodity, what kind of effect does the work have on viewers? In gaining some sort of aesthetic value, does trash no longer signify trash? Is it simply a reconfiguration and relocation of waste, or as Whiteley suggests, a fetishized act (28)? Does the form of its representation register for the viewer on the same level as trash, or has it become something else?

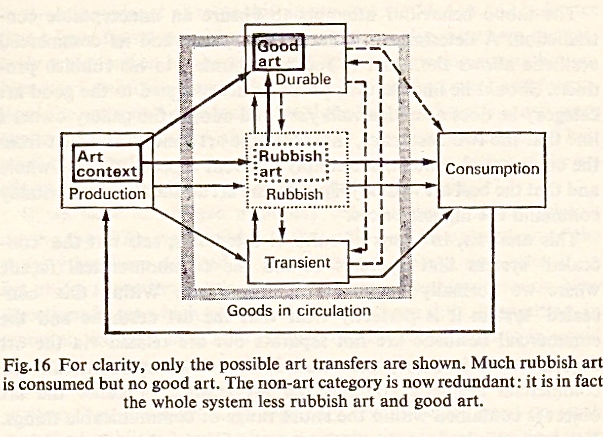

One perspective on art and trash that considers these questions can be found in the work of the social anthropologist Michael Thompson. Writing in the late 1970s, he addressed the status of art and rubbish in relation to production and consumption. His categories of “durables” (valued objects held in museums), “rubbish” (discarded objects), and “transients” (objects in circulation that are not yet classified as either durables or rubbish) identified different states of value granted to objects, states that were changeable and dynamic and could be created and destroyed. Thompson’s three categories have an affinity with Stefanos Tsivopoulos’s History Zero (2013), a work commissioned to represent Greece in the 2013 Venice Biennale. The tripartite film installation presented three characters connected by collecting: an immigrant collecting scrap metal in a shopping cart, an artist who collects images and profits from the immigrant’s scrap metal assemblage, and a wealthy woman collector who makes paper flowers out of money which she then throws away; the shopping cart full of metal objects appears on an exhibition invitation in one of her drawers. The status of the shopping cart changes in the three episodes: first it is rubbish, second, it becomes a transient object in circulation, and finally, it becomes a durable. History Zero explores the role of money and collecting, but more importantly it draws attention to the value of trash and the contested nature of trash-making in relation to the fields of consumption and production. Thompson questioned the stability of the durable object category, however, and its “total removal from circulation” through its accession into the museum and gallery by asking if the system “carries within it the seeds of its own destruction” (103). Although Thompson was highly aware of concurrent developments in auto-destructive art and conceptual art when he was writing Rubbish Theory, the larger implications for destruction and decay in the art of today remain to be examined.

In both the 2013 Venice Biennale and the major international art exhibition Documenta 13 (2012) in Kassel, Germany, trash and destruction were ubiquitous materials and subjects. One subset of this field is trash that retains its status as trash, and when destruction or some kind of transformation is involved, it registers beyond the recycled, commodified object. Artists who present their work as rubbish, in a state of rubbish, or treat it as rubbish and throw it away by destroying it inevitably invite a stage of destruction, either unintentionally, from the slow decay inherent in its retention, or purposefully, through acts of breaking, destruction, and self-destruction. These types of works engage with the viewer in a different way—as compared to the commodified object—by acknowledging the volume of the waste left behind in daily life, and by conceptualizing the fate of the material objects and products as ephemeral and redundant.

3. Waste Preserved and Waste Destroyed

Artists present trash as trash in very different ways. Dieter Roth archived his daily waste in his installation Flat Waste (1975-76/1992), a work which operates as both diary and self-portrait, and which offers the viewer the opportunity to delve into a library of his personal trash. Over the course of a year, Roth saved all of his waste material on a daily basis, flattening or folding it in order to place it all in transparent sleeves in ring binders chronologically filed on shelves. (Roth first made Flat Waste over the period of a year in 1975-6, but some of the volumes lost from the original year were replaced with binders of rubbish collected on the same day in later years.) Between every specially designed shelving unit, a lectern enables viewers to look at a selection of the ring binders–no waste escaped his collection: used toilet paper, toothpaste, train tickets and cigarette butts are all there. Roth’s preservation of decaying waste conveys to the viewer a sense of the scale of one individual’s everyday waste over a single year, and its ultimate fate as excess.

Another more recent work that brings together a unique chronicling of waste, the process of decay, and more recent forms of environmental art can be found in Joshua Sofaer’s The Rubbish Collection at the Science Museum, London (16 June–14 September 2014), part of the museum’s Climate Changing program. The first phase of the project took place over 30 days in June and July, when one month of the museum’s rubbish was collected, sorted and processed for recycling by visitors, staff members, and contractors. The second phase of the project presented an exhibition of the waste material, much of which had been recycled and transformed into paper, HDPE purge blocks, PET jazz flakes, glass sand, or sludge cake. The aesthetic, taxonomic, ordered display transformed waste into museum artifacts. A considerable mass of objects which could not be recycled remained in their original states, pristine, perfectly useful objects, from water bottles to stationery and cutlery items, while other broken things were arranged in groupings that conveyed a sense of the scale of what is left behind when recycling is not possible.

The volume of material generated in 30 days made an installation that increased visitors’ awareness of their decisions to consume and dispose of things. Sofaer wanted visitors “to think about what they don’t want to think about” because disposal breaks the connection between object and consumer, vanquishing waste from the consumer’s mind by making it appear to disappear. After the exhibition closed, all of the recycled material that was borrowed from processing plants was returned, all of the objects that may have been destined for landfill were recycled via specialist trades and organizations “where possible,” and medications were safely destroyed. The project drew attention to waste as waste by aestheticizing and categorizing different forms of both recyclable and unusable waste included in the display; by acknowledging the existence of unusable waste, Sofaer raised it as a problem for the viewer to consider.

By contrast, the intentional destruction of trash relates less to everyday or temporal waste production and more to the idea that a glut of material objects is unnecessary to human life. Many artists incorporate destructive acts into their practice in order to address the ephemerality of the material world, but they also do it to explore the concept of waste on another register. Some artists who destroy objects manage to retain a sense of the object’s original value and purpose. In works such as Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), Cornelia Parker’s suspended fragments of a shed blown up by members of the British army capture the moment of its explosion while retaining a sense of its architectural mass. Susan Hiller’s series of works incorporating the destruction of her paintings through cutting and burning them includes Measure by Measure (1973–ongoing), ashes of annually burned paintings in dated measuring tubes; other works in the series take the form of uniformly-cut sections of paintings tied together to make blocks or bound together to make books, with sections of the painted canvases remaining intact. Ironically, although acquired for museum and art gallery collections and therefore commodities (Thompson would call them durables), such ephemeral, dematerialized artworks signify their own loss of objecthood.

Self-destructive (or self-destroying) art offers viewers the experience of witnessing the demise of the artwork either concurrently or through documentation. Tinguely intended Homage to New York to destroy itself in the sculpture garden of The Museum of Modern Art in New York on 17 March 1960, but instead it caught fire and was later destroyed, leaving behind a film and other documentary imagery which led Michael Landy to try to make another version of Homage because Tinguely’s work “failed to fail” (failed to destroy itself); he has continued to reflect on Tinguely’s work (Sillars 23). Like Homage, Landy’s Break Down (2001) left behind no material remains of his destroyed possessions, although a short film remains, along with an inventory, a publication, and a series of drawings. Once the objects were sorted and grouped, they were listed in an inventory and dismantled, carried along conveyer belts and dumped into a disposal machine; the destroyed material was then sent to a landfill site. The inventory lists all of his objects with equal care, from his own art work and materials to his vinyl record collection (including Echo and The Bunnymen’s 45 rpm single “The Cutter”), from a miniature rubber duck to his cherry red 1988 Saab 900 Turbo16s. Based in a former department store, the event reversed the mechanical actions of production and consumption. Landy relinquished all objects from his personal and professional material life in this profound act of anti-consumerism. Later works such as Art Bin (2010/2014), which involves the disposal of works of art into a giant rubbish bin, also emphasize actions over material remains. The artist’s political attitude toward material objects and their status (as always potentially unnecessary and immutable) links his work to Gustav Metzger and auto-destructive art as well as to other like-minded anti-consumerist artists from the late 1950s and early 1960s such as Arman and Stuart Brisley.

4. Conclusion: Two Newspapers

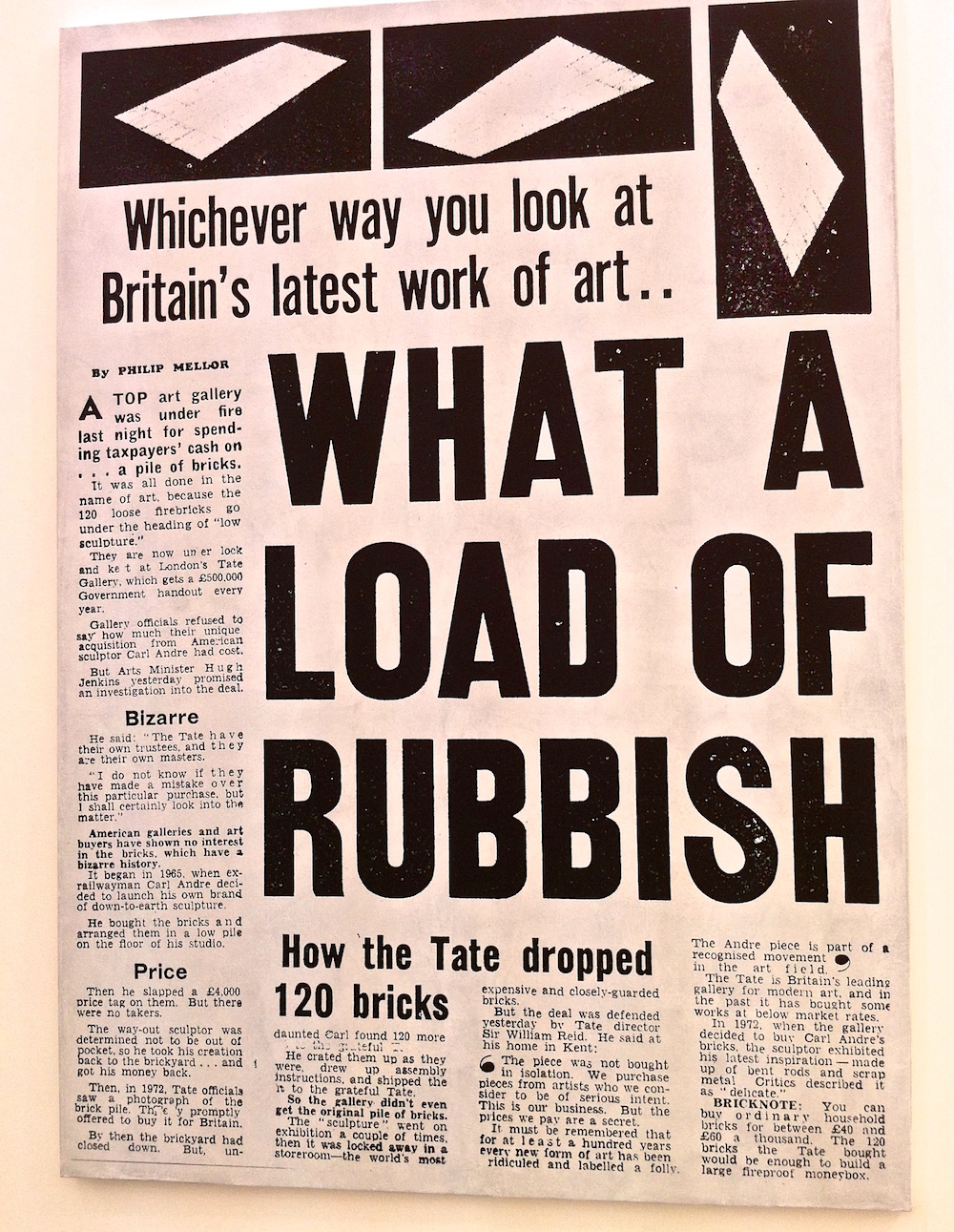

Calling art rubbish (in both senses of the word) is now a familiar media trope, especially when museum exhibits are thrown away by cleaning staff, as was the case with Gustav Metzger’s Recreation of the First Public Demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art (1960/2004) and other works of art (Lack). One iconic historic reference to this idea is the Daily Mirror’s 1976 headline, “WHAT A LOAD OF RUBBISH,” an attempt to capture the public outrage at The Tate Gallery’s (now Tate Britain’s) purchase of Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966), a purchase funded by British taxpayers during an economic slump. (Equivalent VIII was one of eight sculptures made from groups of 120 firebricks stacked in eight different arrangements, and therefore equivalent.) The headline labeling the work as rubbish played with the idea that it was both trash and trashy, even though it was made out of new materials—firebricks—and nothing else. Recently turned into a painting by the collective Claire Fontaine, this iconic headline set the stage for establishing Equivalent VIII, which came to be known as “The Bricks,” as the epitome of “rubbish,” low quality contemporary art.

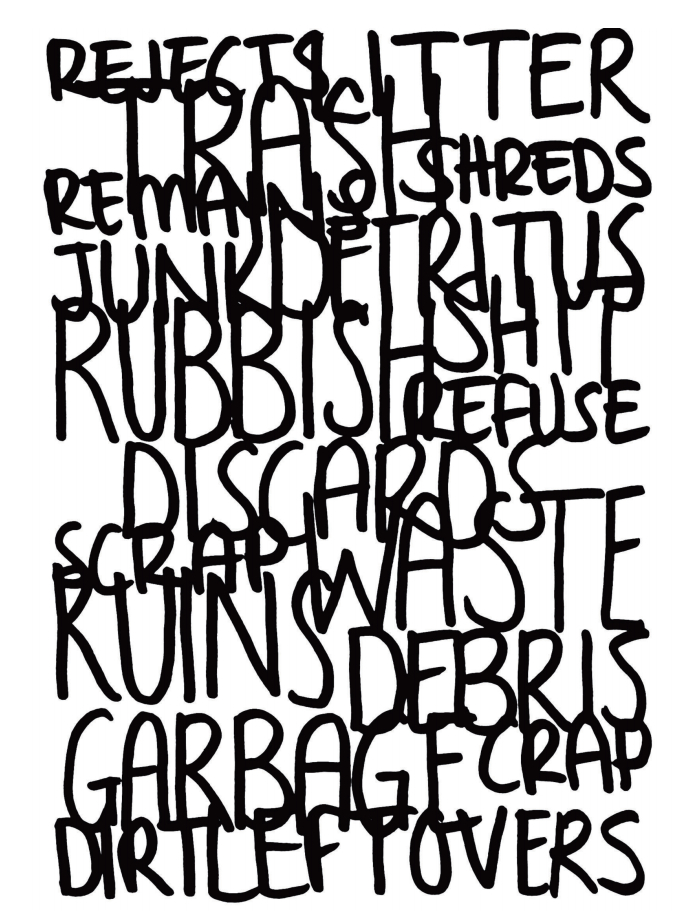

By contrast, no single headline stands out from the entangled mess on the front page of the British artist Alice Bradshaw’s Rubbish Newspaper. A cluster of handwritten, overlapping words vie for attention, as RUBBISH, WASTE, RUINS, TRASH push ahead of DISCARDS, CRAP, REFUSE, LEFTOVERS. Just as the words themselves refer to waste material and something of poor quality, Rubbish Newspaper represents trash and calls itself trash, as one of Bradshaw’s many projects stemming from her Museum of Contemporary Rubbish that critically address the field of trash and art. Bradshaw makes site-specific exhibitions out of rubbish collected in the area and stages conversations about recycling and waste. Her exhibits are artifacts which she acknowledges are “momentarily taken out of the waste stream” and photographed as a way of documenting them as part of the collection after they are exhibited and before they are recycled.

Bradshaw’s acceptance and portrayal of waste as waste and her recognition of the beauty in waste make her Museum of Contemporary Rubbish a project that responds to Žižek’s call to action, although like many artists engaging in similar practices, she does not doggedly pursue the fate of unusable waste. She returns her artifacts to the waste stream, thus avoiding potential commodification and ensuring its eventual destruction. Her process brings to mind Thompson’s categories of durables, rubbish, and transients, states he considered to be fluid, and easily created and destroyed. For many artists now, durables, rubbish, and transients are equivalents, but simply categorized at different stages. Complete destruction may be the most extreme way of defying categorization, taking things out of the waste stream altogether. Whether preserved or partially or completely destroyed, waste presented as waste can address complex questions about the ideal future for, and practical problems of, material life. Unusable waste is only beginning to be acknowledged as a material; its ideal aesthetic future has yet to be realized.

Works Cited

Bradley, Fiona, ed. Dieter Roth: Diaries. Edinburgh: The Fruitmarket Gallery, 2012. Print.

Hawkins, Harriet. “Turn your trash into... Rubbish, Art and Politics. Richard Wentworth's Geographical Imagination.” Social and Cultural Geography 11.8 (December 2010): 805-827. Print.

Lack, Jessica. “Modern Art Is Rubbish.” The Guardian Online. 13 June 2008. Web. 8 Aug. 2014.

Landy, Michael and Clive Lissaman. Workshop on Destruction. 2012. Leaflet.

Sillars, Laurence, ed. Joyous Machines: Michael Landy and Jean Tinguely. Liverpool: Tate Liverpool, 2009. Print.

Thompson, Michael. Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1979. Print.

Whiteley, Gillian. Junk: Art and the Politics of Trash. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011. Print.

Wilson, Andrew. “Destruction/Creation: Act or Perish.” Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm. Eds. Stacy Boldrick and Tabitha Barber. London: Tate P, 2013. 140-153. Print.

Žižek, Slavoj. Living in the End of Times. London: Verso. 2011. Print.

Figures

Figure 1. Landy, Michael, Clive Lissaman, and the participants of the Workshop on Destruction, Wide-Open School, Hayward Gallery. Author’s photograph of collective self-destroying sculpture. 16 June 2012. JPEG.

Figure 2. Diagram representing systems of rubbish art and good art. Michael Thompson. Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1979. 121. JPEG.

Figure 3a. Roth, Dieter. Flat Waste. 1975-1976/1992. Flat materials in transparent sheets in 623 book binders, 5 wooden shelves, 7 bookrests, 4 ceiling lamps. Friedrich Christian Flick Collection, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin. Installation view at The Fruitmarket Gallery. Photograph: Alan Dimmick. JPEG.

Figure 3b. Roth, Dieter. Flat Waste (detail). 1975-1976/1992. Flat materials in transparent sheets in 623 book binders, 5 wooden shelves, 7 bookrests, 4 ceiling lamps. Friedrich Christian Flick Collection, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin. Installation view at The Fruitmarket Gallery. Photograph: Alan Dimmick. JPEG.

Figure 4. Sofaer, Joshua. The Rubbish Collection, Science Museum, London. 2014. Installation. Detail: Electrical Items in The Rubbish Collection. Photograph: Katherine Leedale. JPEG.

Figure 5. Fontaine, Claire. What a Load of Rubbish. 2012. Oil on canvas. JPEG.

Figure 6. Bradshaw, Alice. Rubbish Newspaper. 2013. Newsprint and PDF. JPEG.