From Affective Shareholding to OUR Walmart: Organizing Labor in a Post-Union World

by Christine Labuski and Nicholas Copeland

Published December 2015

“Walmart isn’t on a good path, and someone needs to stand up and speak out. But we always have fear inside of us too.”

–Cindy, OUR Walmart member

“We are here because we truly want to save Walmart. From itself. We are not here to bury Walmart. But . . . to perfect [it] . . . We hope that we can make OUR Walmart representative of the American people. We want Walmart to be the ambassadors when they go into China, into Russia, Germany, and even communist countries. We want them to stand tall as they represent freedom, justice, and equality for all men and women and yes, gays as well. For they too are the heartbeat of the American people.”

–George, OUR Walmart member

Save Money. Live Better.

–Walmart slogan

Cindy and George believe that Walmart is in trouble and needs their help. Both belong to a group organizing for better working conditions for Walmart workers. Founded in 2010 by the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union, as part of their Making Change at Walmart campaign, the Organization United for Respect at Walmart (OUR Walmart) has engaged in a range of confrontations and strategic alliances that are the first such activities in Walmart’s fifty-year history, including protests outside company headquarters and Walton family homes, flash mobs, coordinated and multi-city Black Friday strikes, and the introduction of shareholder resolutions critical of corporate practices. With guidance from UFCW organizers Dan Shledeman and Andrea Dehlendorf, the organization has grown to include thousands of members who are increasingly educated about their legal rights and interests. Most crucially, OUR Walmart has strategically reappropriated Sam Walton’s concept of respect for the individual in order to publicly shame the company into improving the material conditions of its workers. In 2015, the group pressured Walmart into raising their minimum wage to ten dollars per hour, a notable victory for labor against the retailer.

In this essay, we locate the emergence of OUR Walmart in the context of the company’s evolving relationship with its labor force, particularly its promotion of a corporate culture that substitutes symbolic and emotional forms of inclusion for material resources, a practice we call affective shareholding (Copeland and Labuski 12). We then examine OUR Walmart’s use of the term “respect” to publicly shame the company, focusing on specific rhetoric from their campaigns. By showing how Sam Walton’s family values and discourses of respect are meaningless without material rights and collective worker solidarity, OUR Walmart uses shame to reformulate labor norms (Jacquet) and establish a novel space for worker action. Finally, we suggest that rising inequality and precarity pose challenges for state and corporate affective management strategies (Copeland and Labuski, Richard and Rudnyckyj) and provide new terrain for counter-politics focused on inciting and harnessing public feelings.

Affective Shareholding and its Limits

Emerging in the Ozarks in the mid-1960s, Walmart took advantage of a particular labor force—including a cadre of older women—who had been previously ignored as workers. By hiring them to serve customers who were also their friends and family, Sam Walton secured a stable of employees with few expectations and even fewer demands (see Moreton 48-66). This gendered division of labor—in which married and mature women worked for younger male managers—solidified Walmart’s reputation as a family business in a time and region that favored mom and pop retail outlets over Northern chains. And though the company’s former profit sharing program and discounted stock options (through which many early employees became wealthy) were crucial to maintaining a loyal workforce, historian Bethany Moreton insists that these familial dimensions of Walmart’s business model should not be underestimated (67-85).

Walmart also fashioned a religiously inflected business philosophy, known as servant leadership, which framed managers and hourly employees as equals in a mission for the greater good. This leveling strategy was further complemented by practices like the morning cheer, referring to employees as associates, and policies such as the Open Door, which enabled workers to air grievances and share ideas directly with management (Associate Engagement 92). Indeed, several of the retailer’s now-famous “Rules for Building a Business” illustrate Walton’s attunement to the non-economic benefits of these affective shareholders, including Rule #5, “Appreciate”: “Nothing else can quite substitute for a few well-chosen, well-timed sincere words of praise. They’re absolutely free—and worth a fortune.” Through these and other practices, many employees came to understand their in-store labor in terms that transcended economic exchange. Walmart’s embrace of servant leadership recalibrated the work associated with retail service from a mundane series of menial tasks into a humble mode of sanctified capitalism. Their service to and interactions with customers built community and undergirded Walmart’s stated mission of helping society. This folksy style of affective management aimed to stabilize a workforce through positive feelings of purpose and belonging.

Walmart’s claims that their employees preferred the family model to unionized “third-party representation” contrasted sharply with their aggressive and zero tolerance anti-union activities—including closing an entire store in Jonquiere, Quebec after associates voted to form a union (see also Walton 164-7). Walmart’s anti-union tactics, which include routinely submitting their employees to training films, literature, and other coaching, in addition to prohibiting speaking to other employees about labor issues, have rendered many associates reluctant—if not afraid—to collectively organize, contradicting the spirit of the Open Door policy. In his autobiography, Made in America, Walton couched Walmart’s anti-union policies in the affectively inclusive language of servant leadership:

[H]istorically, . . . unions . . . have mostly just been divisive. They have put management on one side of the fence, employees on the other, and themselves in the middle . . . And divisiveness . . . makes it harder to take care of customers, to be competitive, and to gain market share. The partnership we have at Wal-Mart—which . . . [involves] a genuine effort to involve the associates in the business so we can all pull together—works better for both sides. (166)

Walton’s language here is important for two reasons, the first being the seamless co-assemblage of profit, customer service, anti-union sentiment, and company loyalty which, for Walton, was at the heart of his company’s success. Second, Walton’s de-legitimation of unions denies the very possibility that his employees would identify as (a class of) workers on their own terms. Pulling together is fine, in other words, as long as it’s for the good of the company.

Though this family approach worked well in Walmart’s early years, in the then-relatively homogeneous Ozarks, the company’s business model changed markedly in the 1980s and 90s. Intensive domestic and international expansion led the retailer to begin prioritizing low prices over familial inclusion and, as profit sharing ended, corporate profits and executive salaries soared. “Family” became more folklore than reality and, for hourly employees whose wages were squeezed to keep prices low, the Open Door felt increasingly closed. It was this growing estrangement between workers and managers that shaped OUR Walmart’s emergence and that continues to underpin much of their rhetoric and action.

In the present day, Walmart’s internal stratification is acutely felt by head-of-household hourly employees, who at times must resort to local, state, and federal aid in order to care for their own families. Walmart’s contemporary employees live far more precariously than did the company’s original workforce, including people like LaRanda Jackson who, living on an $8.75 hourly rate, “can’t afford soap, toothpaste, tissue” and, at times, “washing [her] clothes” (Tabuchi and Greenhouse), and J.P. Ashton, who reminds visitors to the OUR Walmart website that “[p]eople take being able to buy lunch for granted” (“Why I Joined”). Moreover, Walmart workers have few opportunities for advancement and legal redress, underscored most recently by the failure of the Wal-Mart vs. Dukes class action lawsuit that aimed to procure equal pay and promotion for 1.6 million of the company’s female employees. With these affective, legal, and professional avenues foreclosed, OUR Walmart stepped in as an energizing and creative resource for those hoping to secure and expand their rights as workers.

Redefining Respect

Walmart’s official culture celebrates “respect for the individual” (Walmart), but respect is an ambiguous concept. It refers to admiration and high regard but does not necessarily signify economic equality or extend beyond emotion. It is incompatible with discriminatory treatment but lacks specific content and may be experienced unevenly. Workers often find it difficult to feel respected as individuals when labor itself is devalued. For OUR Walmart, the company’s low wages and inadequate hours are disrespectful to them as kin, i.e. “[i]f this is how family is treated, then I would rather not have [one]” (Velasco). This reading of respect collapses both affective and material modes of inclusion, as well as individual and collective respect, evincing the tension these associates experience between being nominally part of a family and being workers with distinct interests. When member Mary Pat Tifft read the now-notorious company memo that detailed proposed upper management strategies for nudging better-paid senior associates out the door, she felt “degrad[ed],” lamenting “[r]eading that tells you how they feel about [us]” (Berfield).

OUR Walmart’s alternative definition of respect relies not on individual advancement, but on a definition of “Liv[ing] Better” that is based in collective well-being and material rights, untethered to market rationality and not limited to “Sav[ing] Money.” Their critique is immanent, with demands rooted in Walmart’s own principles of respect and inclusion. Claiming to be the “real” Walmart, they frequently wax nostalgic about Sam Walton’s mythic respect for his associates and, by labeling protest and collective organizing as company-sanctioned requests for Open Doors, they challenge senior management to adhere to the company’s core principles. These tactics, which include requests for more work and the opportunity to serve customers in cleaner and better-stocked stores, seem conciliatory when compared with more confrontational forms of labor organizing. But OUR Walmart’s redefinition of respect also implies a substantial package of material labor rights. Moreover, by linking the concept of respect to everything from a minimum hourly wage to race and class-based identity politics, OUR Walmart has successfully intersected with groups with broader political strategies, such as the Occupy, Fight for Fifteen, and #BlackLivesMatter movements. These actions in particular have begun to shift the locus of OUR Walmart’s identity from members of a family to workers with a collective interest. And though OUR Walmart may be nostalgic for a world that never existed, their focus on improving worker conditions collectively is radical nonetheless, given that such demands are incompatible with the standard low-wage business model in the current moment of neoliberal capitalism.

The Politics of Shame

OUR Walmart redefines respect via direct action and a savvy social media campaign aimed to generate ill will toward the company by exposing their hypocrisy. The group engages in a public politics of shame (Jacquet), pressuring the retailer to improve its practices by drawing attention to worker mistreatment, inequality, and corporate greed. OUR Walmart consistently contrasts the difficult details of its members’ lives with the egregious wealth of the Walton family. Typical email communications describe workers struggling to keep food on the table, and reference their need to access public assistance; well-rehearsed phrases include “making ends meet,” “paying the rent,” and “feeding our families”—families abandoned by Walmart’s quest for profits. The organization emphasizes the ordinary details of working class lives in America: hectic and tedious labor, grim and tense home situations, and little hope for advancement—realities that they animate with direct action (OUR Walmart email listserv). In a striking example of this, Los Angeles-based members undertook a twenty-four hour hunger strike in June of 2015 in order to depict Walmart’s “starvation labor” policies (Kann).

OUR Walmart lambasts heartless managers who deny them raises, cut their hours, juggle their schedules, and force them to work sick. They demand living wages and healthcare, as well as an end to unfair “coaching”—Walmart’s euphemism for management. Their campaigns also highlight the plight of single mothers and people of color, two categories overrepresented in Walmart’s workforce. A campaign called Respect the Bump began when a pregnant Maryland associate named Tiffany Beroid was forced to take an early leave of absence rather than be assigned lighter duties, as her doctor had requested. Left in dire straits, Tiffany found other expectant mothers online with similar stories, and OUR Walmart helped the group to stage protests, write letters to management, and introduce a resolution at the 2014 shareholders meeting. Exposed as cold and uncaring, Walmart changed its policy for pregnant women (DePillis).

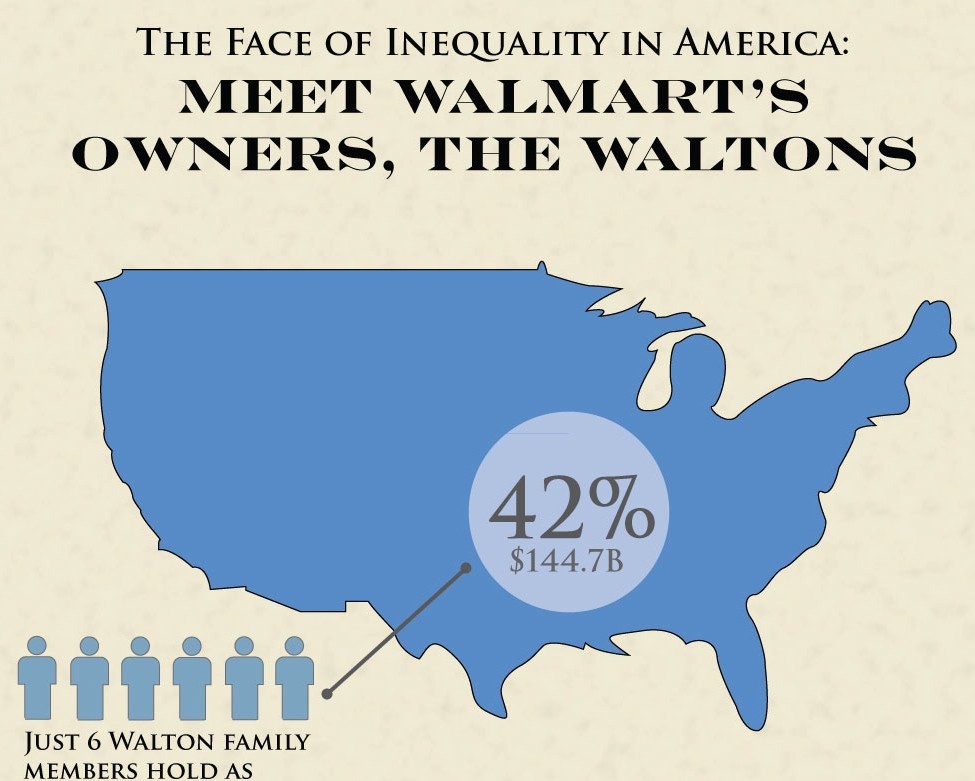

Communiqués and protests denounce retaliatory firings, transfers, and reduced hours—all illegal responses to worker actions. The group frames their struggle as a classic David and Goliath story, encouraging audiences to view them as sympathetic and exploited underdogs. The group highlights the glaring injustice of the Walton family’s wealth having been amassed through their employees’ hard work and mistreatment. Indeed, OUR Walmart makes endless references to the grotesque immensity of this wealth, equivalent to the net worth of the bottom 42% of the US population, and to the unpatriotic tax havens in which it is allegedly stashed.

Drawing attention to the Walton family allows OUR Walmart to negatively contrast their own family situations, as in this excerpt from a 2015 email: “Walmart, the largest private employer in the world, owned by the richest family in America, can afford to provide my co-workers and me, with enough to support ourselves and our loved ones” (OUR Walmart email listserv). Such comparisons assert that economic inequality of these proportions is in itself shameful.

Affective Politics in an Unequal World

In the wake of firings and retaliations, the demands of some OUR Walmart members have become both more explicitly radical and more substantive. These members articulate with what Peter Frase and others have called “the precariat,” a contemporary category of workers who know that “affordable housing, education, and child care are just as much ‘labor issues’ as what happens during working hours” (11). Some core members have begun to ally with other movements, such as #BlackLivesMatter and Occupy, as well as with Walmart associates from other countries.

In 2012, after helping nearly twenty OUR Walmart members file workplace retaliation lawsuits with the National Labor Relations Board, OUR Walmart went to Bentonville to demand—via an Open Door request—that the retaliation stop, threatening a Black Friday strike if Walmart did not comply. The group was met by senior management, including vice president David Scott, who proposed one-on-one meetings. Led by seasoned member Venanzi Luna, the group engaged with Scott with an Occupy-inspired mic check, declining individual meetings in favor of a continued collective presence. After Luna refused the executives’ offer by stating: “We are not here individually. We are here as a group,” she was swiftly echoed by a group of surrounding members, chanting: “WE ARE NOT HERE INDIVIDUALLY. WE ARE HERE AS A GROUP” (“OUR Walmart’s Mic Check”; see also Featherstone).

Walmart critic and labor rights advocate Liza Featherstone argues that it has “long been clear that [Walmart]’s relationship with its workers would never be ‘transformed’ without dramatic action from the workers themselves.” At issue for us is how to understand the transformative potential of OUR Walmart and how to interpret the broader cultural narratives and affective shifts with which the group intersects. Having been assembled by the UFCW from a pool of “dedicated employees with a couple of complaints” (Berfield), OUR Walmart is now a heterogeneous group of workers mobilizing a mix of radical goals and centrist rhetoric. As they have now made plain in their OUR Walmart petition, they are “here as a group,” one that wants “to show Walmart that we truly are the family they claim to be” while simultaneously having “the moral courage to see issues within our workplace and to organize for constructive change.” Their efforts ground an expanded conception of worker rights in a fundamental right to be treated with respect.

Beyond specific victories, the group’s efforts appear to be paying off in affective connections to counterpublics similarly alienated by growing inequality and the precarious and dead-end nature of wage labor in the neoliberal era. OUR Walmart is making experiences of inclusion and belonging available to its members in ways that the corporation now finds threatening. Speaking of her first trip to Bentonville, which she admits was “really scary,” Mary Pat Tifft says that listening to other associates’ stories “made [her] want to speak louder,” while Colby Harris found striking at Store #1 (in Rogers, Arkansas) to be “exhilarating” (Berfield). For these reasons, we concur with labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein, who argues that Walmart may have made a “tactical mistake” (Berfield) in acknowledging OUR Walmart’s existence, thereby granting legitimacy to a force that is increasingly beyond their control. Indeed, OUR Walmart has placed the company in a delicate position regarding their aforementioned recent decision to raise starting hourly wages. By insisting that the company “make[s] wage adjustments all the time” (Tabuchi), and constricting the recent raise in hourly rates to ten dollars, rather than heeding OUR Walmart’s request for fifteen, the company once again violates its own corporate rhetoric. Rule #7, it turns out, is that “you must listen to what your associates are trying to tell you.”

OUR Walmart is a product of Walmart’s authoritarian business culture and the breakdown of the company’s legendary mechanisms for affective inclusion. The organization’s members creatively draw directly on these inclusive family ideologies and accuse the company of failing to live up to its own values. They use social media to publicly shame the corporation, gather new members, and pressure the company to change its practices. Moreover, its members have developed affective connections to a collective identity, refusing to be individualized—and therefore divided—by Walmart management. Although their nostalgia for an imaginary inclusive capitalist past can seem regressive, OUR Walmart members insist on dignified lives and they work to stigmatize routinized exploitation, rhetoric that resonates with the commonsense understanding that people who work hard should not have to live in insecurity. Given the incompatibility of their demands for respect with current labor conditions and market logic, groups like OUR Walmart, and the shame they incite, will remain a feature of social and political life in an era of rising inequality and corporate dominance.

We do not get enough hours.

We cannot take care of our families.

Because our managers bully associates; we are on strike against retaliation.

We are not here individually.

We are here as a group.

As associates, we are disrespected at work.

Every day.

Open Door. Does not work.

We’re here as a group.

As OUR Walmart. OUR Walmart.

Let’s roll.

Works Cited

Ashton, John Paul. “Why I Joined.” OUR Walmart. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. <http://forrespect.org/why-i-joined/>

“Associate Engagement.” Walmart.com. 2013. pag. 92. PDF file. 30 Oct. 2015. <https://cdn.corporate.walmart.com/39/97/81c4b26546...>

Berfield, Susan. “Walmart vs. Union-Backed OUR Walmart.” Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg Business. 13 Dec. 2012. Web. 6 Apr. 2015. <http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2012-12-13/wa...>

Copeland, Nicholas and Christine Labuski. The World of Wal-Mart: Discounting the American Dream. New York: Routledge, 2013. Print.

DePillis, Lydia. “Under Pressure, Walmart Upgrades its Policy for Pregnant Workers.” Washington Post. The Washington Post. 5 Apr. 2014. Web. 7 April 2015. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonkblog/wp/201...>

Featherstone, Liza. “Walmart Workers Walk Out.” The Nation. The Nation. 17 Oct. 2012. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.<http://www.thenation.com/article/170653/walmart-workers-walk-out#>

Frase, Peter. “The Precariat: A Class or a Condition?” New Labor Forum 22.2 (2013): 11-14. Print.

Jacquet, Jennifer. Is Shame Necessary? New Uses for an Old Tool. New York: Pantheon. 2015. Print.

Kann, Julia. “California Walmart Workers Go on Hunger Strike after Stores Closed in ‘Retaliation’ for Organizing.” In These Times. In These Times and The Institute for Public Affairs. 29 May 2015. Web. 30 Aug. 2015.<http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/17999/walmar...>

Moreton, Bethany. To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2009. Print.

OUR Walmart. “OUR Walmart’s Mic Check at Home Office.” YouTube. 10 Oct. 2012. Web. 6 Apr. 2015.

OUR Walmart. “Why Join.” OUR Walmart. Web. 7 Apr. 2015. <http://forrespect.org/join-now/>

Richard, Analiese, and Daromir Rudnyckyj. “Economies of affect.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15.1 (2009): 57-77. Print.

Tabuchi, Hiroko. “Walmart Raising Wage to at Least $9.” New York Times. New York Times. 19 Feb. 2015. Web. 9 Apr. 2015.<http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/20/business/walmart...>

Tabuchi, Hiroko and Steven Greenhouse. “Walmart Workers Demand $15 Wage in Several Protests.” New York Times. New York Times. 16 Oct. 2014. Web. 6 Apr. 2015. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/17/business/walmart...>

Velasco, Schuyler. “Walmart Legal Troubles Mount as Black Friday Walkout Looms.” Christian Science Monitor. Christian Science Monitor. 23 Oct. 2012. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.<http://www.csmonitor.com/Business/2012/1023/Walmar...>

Walmart. “Culture: Our Beliefs.” Working at Walmart. corporate.walmart.com. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.<http://corporate.walmart.com/our-story/working-at-...>

Walton, Sam. Made in America: My Story. New York: Bantam, 1992. Print.

Figures

Fig. 1: Reinstate Illegally Fired Workers Now. “After Nationwide Day of Protests, OUR Walmart Announces Massive 2013 Black Friday Strikes.” RetailJusticeAlliance.org. 10 Sept. 2013. JPEG. 13 Oct. 2015.

Fig. 2: Protesters Rally, Betty Dukes Speaks. “Wal-Mart vs Dukes: Women rally, original plaintiff speaks at Supreme Court.” DC Direct Action News. 29 Mar. 2011. JPEG. 30 Oct. 2015.

Fig. 3: The Face of Inequality in America. Walmart1percent.org. 2013. JPEG. 30 Oct. 2015.