The Price of Eternal Vigilance: Women and Intoxication

by Michelle McClellan

Published April 2016

In Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget (2015), thirty-something writer Sarah Hepola recalls her reaction upon encountering a health education pamphlet when she was in college. As she read through the list of questions intended to help students identify whether they might have a drinking problem, she stopped at this question: “Do you ever drink to get drunk?” Her response: “Good lord. Why else would a person drink? To cure cancer? This was stupid” (11). Hepola’s reaction is a straightforward acknowledgement of the psychoactive power of alcohol and her desire for its effects. Her exasperation suggests that intoxication is the whole point and only narrow-minded authors would even pose the query. Hepola invites the reader to join her in dismissing this question—and perhaps the entire public health, disease-model-of-addiction enterprise it represents—as an earnest but misguided attempt to deny everyone the pleasures of drinking. By narrating her reaction in this way, Hepola claims intoxication—not just alcohol consumption—as her right; she finds drinking and drunkenness to be empowering for her as an individual and as a woman in a male-dominated world.

Yet Hepola offers this defense of intoxication in the context of her recovery memoir, a narrative form in which an author, having achieved abstinence from alcohol or drugs, recounts her life story. Hepola describes how her drinking escalated and the emotional and social costs it brought; the fear she felt after blacking out; her ultimate realization that she had to stop drinking; and her struggle to achieve sobriety. Any reader at all familiar with the genre, or any reader who casually consults the book jacket before beginning the text, will appreciate that Hepola’s encounter with the pamphlet is only the beginning of her journey. Indeed, Hepola’s reaction to the intoxication question is intended to signal that she is in trouble, even if she does not know it yet. According to the conventions of the genre (Crowley), the reader can be confident that Hepola herself will change her mind, ultimately foreswearing intoxication as a legitimate goal. As a result, Hepola’s initial defense of intoxication rings hollow and serves to reinforce rather than undercut the warning represented by the question: “yes, I sometimes drink to get drunk” is a danger signal after all. Given the prevalence of such memoirs, much of what we hear about intoxication comes from accounts by those individuals who have renounced it.

Almost one hundred years after national Prohibition took effect in the United States, banning the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquor by Constitutional amendment, women’s drinking remains fraught in American society. Hepola’s memoir is only one of many recent books on this topic, including journalistic accounts of a supposed “epidemic” of drinking among well-educated, middle-class women and a spate of recovery memoirs like Hepola’s (see Glaser, Johnston, Knapp, and Scoblic), where an individual woman recounts the story of her drinking, her descent into alcoholism, and her ultimate recovery. All of this literature shows that a gendered double standard persists in the twenty-first century.

Part of this double standard has to do with alcohol itself. Alcohol is a drug, but it has a unique history and position in American culture. Since the repeal of Prohibition in the United States in 1933, powerful economic, political, and cultural forces have worked to normalize alcohol as a legitimate consumer good, distinct from recreational drugs that remained illegal and illicit. While some Americans do not drink at all—so the category of “abstainer” remains—professional experts and the wider society alike have sought to draw a line between “normal drinker” and alcoholic, a counterpoint to that line between abstainer and drinker. But as Hepola’s encounter with the health pamphlet shows, it can be hard for the center—“moderate drinking”—to hold. It might seem obvious that the point of doing drugs, including alcohol, is to achieve an altered state, but the assumption in that pamphlet that drinking to get drunk is an example of problematic use shows how ambivalent Americans are about intoxication. Importantly, the question does not ask about the quantity of alcohol consumed; instead, it focuses on one’s motive for drinking.

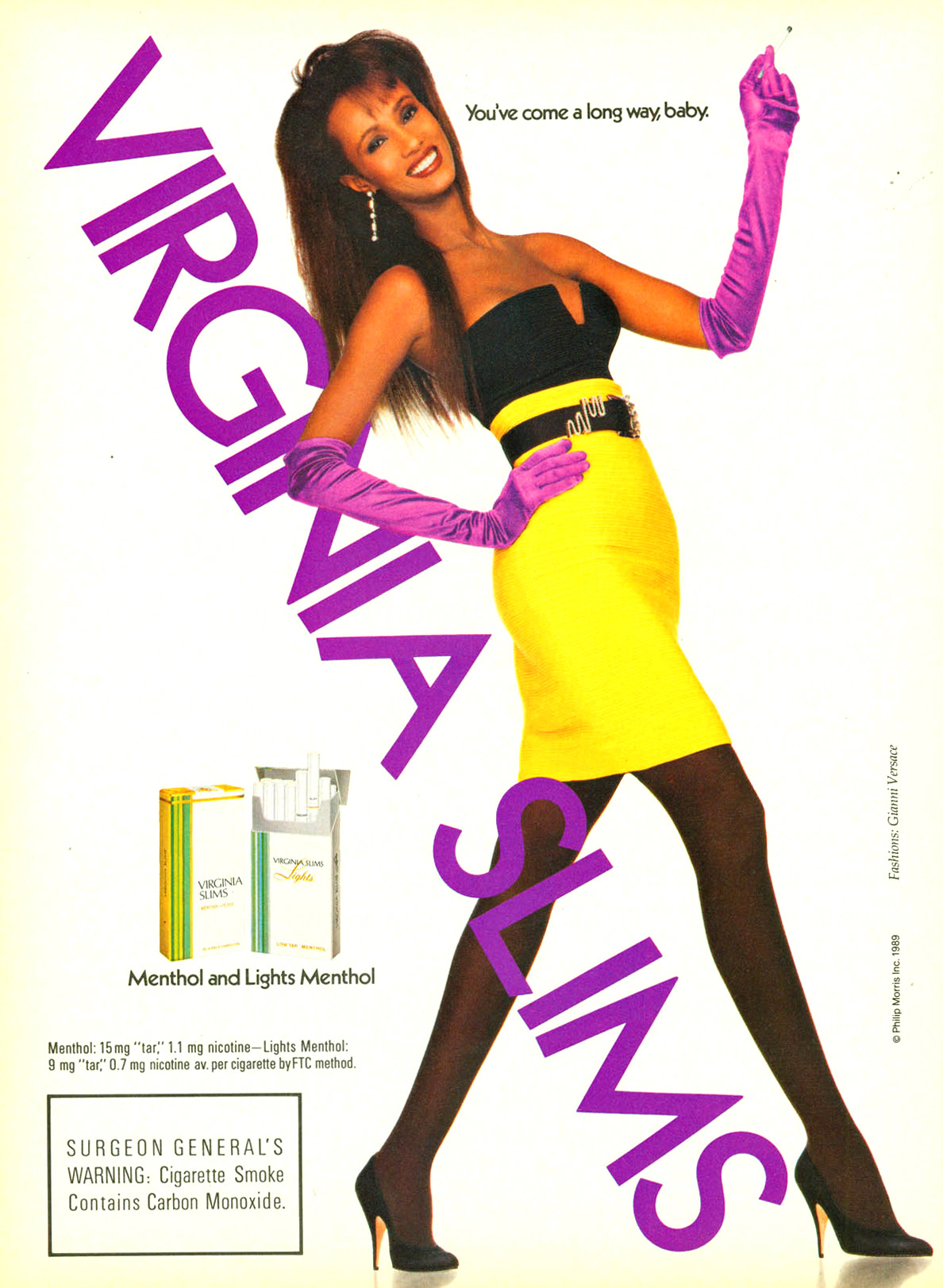

The urge to alter consciousness may be universal, as Stuart Walton explains in his Out of It: A Cultural History of Intoxication (Walton 2), but even if so, we monitor and judge it very differently depending on who is doing it. We have devised elaborate rituals and policies to try to bring order to a desire that is fundamentally about dis-order and dis-inhibition. Age, race, class, and social position have all been important variables in how drug taking is assessed by those in positions of power and by the wider society. And gender remains one of the most significant dividing lines of all. As marketers understand very well, drinking and drug-taking practices both reflect and shape gendered conventions of behavior. Think of the Virginia Slims cigarette advertisements “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby,” for example, or wine coolers in pastel colors. These products attempt to capitalize on a period of social transition: today, women’s drinking is much more socially acceptable than in the past.

Yet women’s drinking represents an area of struggle in which lingering ambivalence about alcohol collides with confusion and concern over women’s changing roles, resulting in a gendered double standard of harsher judgment toward women who drink, particularly those women who seem to choose intoxication. This double standard, in turn, can reinforce conventional boundaries between women and men, extending beyond alcohol consumption per se to regulate women’s behavior in other realms such as sexuality and motherhood. And with women’s roles already in flux, the destabilizing prospect of intoxication proves especially threatening. Intoxication promises a “time out,” a release from one’s usual or expected behavior. As women navigate an unstable social and cultural landscape, this potential release looks both exciting and dangerous.

Intoxication highlights women’s vulnerabilities and responsibilities, amplifying—or compromising—each. Of course, drunkenness brings risks for anyone: accident or injury; exacerbation of existing health issues; doing or saying something without the usual psychological filter, which may result in social embarrassment if nothing else. But drunk women also face gender-specific perils: particularly sexual assault or harassment. In this way, intoxication magnifies a danger that women face even when sober. At the same time, our society assigns women a near-sacred caretaking role, especially for children. Here, women’s intoxication is understood to pose a threat not to their own safety but to their ability to protect vulnerable others. In either case, intoxication brings gender-specific dangers for women in terms of their well-being and their capacity to fulfill their part of the social contract.

These social meanings associated with drinking shape our understanding of the science of alcohol. As a society, we remain determined to find sex and gender differences in drinking patterns and in the effects of alcohol on the body. Popular media frequently publishes newly discovered scientific findings that seem to justify long-standing beliefs: women’s bodies metabolize alcohol differently, thanks to differences in proportions of body water and in enzyme levels. The number of drinks it takes to count as a “binge” therefore differs as well. Biological differences may be real, but they are accorded an exaggerated social and cultural meaning. When it comes to language, even modern-day Americans have no rhetorical equivalent to “drinking like a gentleman.”

Making sense of women’s drinking can be a challenge even for feminists, due in part to the long shadow cast by the temperance movement. Examining alcohol treatment and policy in the late twentieth century, Laura Schmidt and Constance Weisner offered a useful model of “dry” and “wet” feminism that can be expanded beyond that particular era. “Dry” feminists focus on health, risk, and moderation, underscoring the risks that drinking—whether their own or someone else’s—can pose to women’s well-being. Dry feminists thus acknowledge women’s physical, political, economic, and even psychological vulnerabilities. Temperance advocates of a century ago can be considered dry feminists. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, for example, leveraged cultural beliefs about women’s pure and pious nature into a widespread social movement and even formal political power, arguing that alcohol should be banned because it unleashed men’s violence against women, while wives lacked any financial or legal recourse. Today, alcohol remains a factor in intimate partner violence and sexual assault—but now women are more likely than they were a century ago to be drinking along with the men. On college campuses, predatory men have learned to “weaponize” alcohol, capitalizing on a drinking culture that incapacitates many young women. A dry feminist perspective insists that women must curtail their drinking and remain vigilant. Such a double standard might not be fair, but according to this view, women cannot afford to let their guard down.

Nineteenth-century temperance advocates grouped women with children as innocents who needed to be protected from men’s drinking, gaining moral authority from their position as mothers. This legacy can be clearly seen in Mothers against Drunk Driving (MADD), founded in 1980 by a woman whose child had been killed by an intoxicated driver. At almost the same time, physicians and scientists named Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS)—a constellation of birth defects that result from maternal drinking during pregnancy (Golden). Today, warning labels, social sanction, and even the plots of television shows and movies all communicate that any drinking during pregnancy poses an unacceptable risk to the fetus. The nearly-simultaneous developments of MADD and FAS reinforced the idea that good mothers do not drink; instead, good mothers monitor their own behavior to protect children and campaign against the harms caused by drinking.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome has played a critical role in rendering women’s drinking suspect and in eroding a middle ground of moderation for women. Alcohol can cause birth defects, but policy—such as warning labels on wine bottles—has overshot scientific and clinical findings which indicate that very high levels of consumption lead to harm. No researcher can guarantee that there is a way to drink during pregnancy that does not risk damage to the fetus, and so a measure of good (conscientious, health-oriented, and selfless) motherhood is to abstain completely from drinking.

And if abstinence from alcohol is the standard during pregnancy, what about afterward? The rise of alcoholic beverages aimed directly at mothers (MommyJuice Wines), baby clothes emblazoned with “Mommy drinks because I cry,” and complaints about strollers blocking tables at hip bars, all indicate that mothers drink.

But scrutiny and criticism of women’s drinking habits remain, even once the children are born. The particular risk associated with pregnancy—that the alcohol could directly affect the developing fetus—may have passed, but alcohol still threatens a woman’s ability to be a good mother. If she becomes intoxicated, she relaxes the vigilance that defines conscientious parenting today. Worse, intoxication signals that she wanted a time-out, a break from mothering—and that desire indicates that something is wrong with her as a mother, and thus as a woman, whether she is alcoholic or not. Tellingly, these beverages and clothes indicate mothers’ defensiveness about drinking, demonstrating that social sanction remains strong even if behaviors are changing.

In contrast to dry feminists who emphasize the potential risks associated with alcohol and emphasize gender difference, “wet” feminists see women’s access to alcohol, drugs, and other forms of public recreation and pleasure as progressive and emancipatory. Wet feminists emphasize gender equality and the ways in which drinking practices can foster and demonstrate it. Some wet feminists simply try to avoid discussion of circumstances wherein women’s alcohol use seems to heighten risk, such as that of sexual assault, while other wet feminists insist that the real issue there is men’s behavior, not women’s drinking at all—and that asking women to change their behavior is sexist, demeaning, and not even the most effective approach.

Wet feminists have measured progress in terms of transgression into public space such as bars from which women—at least “respectable” women—were once excluded. The 1920s flapper who drank cocktails in a speakeasy right along with men is a classic example of wet feminism. Throughout the twentieth century, the claim was made over and over that women were “closing the gap” with men’s consumption rates, a phenomenon somehow related to a quest for equality, according to many commentators. Hepola herself makes this connection: “as women’s place in society rose, so did their consumption, and ‘70s feminists ushered in a new spirit of equal-opportunity drinking” (9).

Wet feminists and other commentators who link public drinking with gender equality do not necessarily engage with the issue of intoxication. But in her memoir, Hepola describes how being drunk seems to bring superpowers, allowing her to be the star of the show and granting her a sense of freedom and autonomy she had never known before. “Booze gave me permission to do and be whatever I wanted . . . And the crazy thing about finally asking for what you wanted is that sometimes—oftentimes—you got it” (72-73). Like many alcoholics, Hepola recalled how drinking helped her overcome a crippling sense of self-consciousness. But in her telling, intoxication overrides not just individual psychological characteristics like shyness but also inverts social expectations that women will remain on the sidelines, cheering on the men. Recalling how her mother and aunt watched the kids while her uncles drank, Hepola drinks in part to demand a different role for herself: “Screw that. I wanted to be the center of the party, not the person sweeping up afterward” (9).

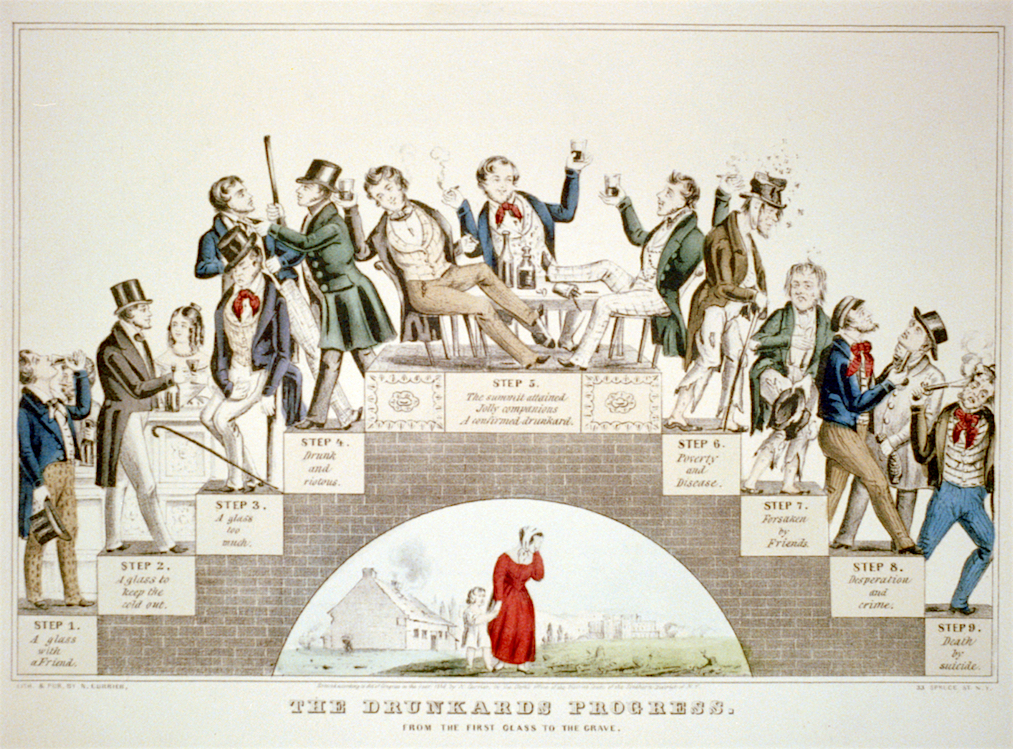

Yet Hepola presents her celebration of intoxication and the liberation it brings in the context of her recovery memoir, suggesting that the empowerment she felt was transitory and illusory. The genre of recovery narrative reinforces the belief that alcoholism, and addiction more generally, is a progressive condition. This concept gained significant traction through the twentieth century, which is not surprising since it added a scientific gloss to an older model of the “Drunkard’s Progress.” As illustrated in a mid-nineteenth-century lithograph by Nathaniel Currier, the drunkard moved inexorably from a “glass with a friend” through poverty, illness, ostracism and eventual death, leaving his crying widow and child to mourn.

Twentieth-century iterations of a “disease model” of addiction echoed and reinforced this trajectory, to say nothing of drug education in schools, which consistently issued dire warnings against “gateway” drugs. In all its forms, this paradigm reflects “the idea that all substances are eventually habit-forming, and that all episodes of use are either the consequence of some irresistible chemical slavery, or at least a staging-post on the way to that condition” (Walton 79).

To better understand the scientific influence and cultural power of the assumption that drinking will lead to alcoholism almost as if pulled by gravity, it can be constructive to compare alcoholism with homosexuality as a category of identity and as a diagnosis. In the late nineteenth century, an individual might engage in erotic acts with a person of the same gender but these acts did not coalesce into an identity or even fixed label. Then, in the twentieth century, experts such as sexologists claimed that anyone who engaged in these acts represented a particular kind of person, a homosexual (Terry). That shift from “acts” to “identity” produced complicated results: increased stigma, surveillance, discrimination, and harassment, but also a more coherent sense of self for many individuals and—although it took decades to realize this—an influential political movement.

Similar imperatives regarding categorization have animated alcohol and drug use, as we have seen. During the temperance era, millions of Americans signed the pledge to abstain from alcohol. Others drank occasionally, while still others could be identified as habitual drinkers, even “drunkards.” The logic behind Prohibition held that alcohol itself was to blame, since it was such a powerful substance that it could entrap almost anyone. But in the post-Repeal climate, we cannot blame alcohol itself—after all, it is a legal substance, advertised everywhere as a benign consumer good and woven into mainstream social life in myriad ways. Today, the problem, if there is one, must be in you. Accordingly, the obligation to scrutinize one’s own drinking practices is very high indeed, due to the success of a public health model of alcoholism as a progressive condition and the diffusion of “recovery culture” through a range of venues (Travis), including memoirs such as Hepola’s. Does drinking make a person an alcoholic? Does liking to drink make a person an alcoholic? At what point does a series of drinking episodes coalesce into an identity of “alcoholic”?

In this context, one’s motive to drink becomes all the more important, which brings us back to the pamphlet Hepola encountered: Do you ever drink to get drunk? In further parallels with sexuality, some forms of pleasure are more legitimate than others; in the case of drinking, the act might be the same, but the difference lies in intent, an inescapable question within a disease model framework. Sex for procreation or to strengthen a committed partnership is one thing, perhaps akin to moderate drinking that renders social interactions more pleasant. “Casual” sex, on the other hand, echoes drinking to get drunk in the sense of seeking to satisfy oneself in the moment. And it is no accident that the two seem to go together, as Hepola notes: “Alcohol is the greatest seduction tool ever invented” (186).

Accepting and even embracing the identity of “alcoholic” is, of course, central to the 12-Step paradigm of Alcoholics Anonymous. That process represents a kind of “coming out” like that practiced by lesbians and gay men. Many alcoholics, like the men and women who advocated for a medical diagnosis of homosexuality in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, have expressed enormous relief at having a name (alcoholism) to assign to a drinking pattern that had gotten out of control. But unlike homosexuality today, claiming the label of alcoholic brings with it the obligation to reject the behavior that created the identity in the first place—there’s no going back. While sexual identity might still accommodate fluidity, the path to addiction is understood to be a one-way journey.

From the point of view of her recovery, Hepola offers a cautionary tale even as she enumerates the benefits she once got from alcohol: “Drinking had saved me. When I was a child trapped in loneliness, it gave me escape . . . When I was a young woman unsure of her worth, it gave me courage. When I was lost, it gave me the path . . . And even in the end, when I was tortured by all that it had done to me, it gave me oblivion” (131). Hepola’s eloquent account provides a glimpse into the appeal of drinking and drunkenness for women in particular, but the fact that she writes from a position of recovery makes the reader question the value and meaning of intoxication. If she wound up an alcoholic, would anyone who took a drink for courage or pleasure also become one?

The cultural meaning of intoxication is profoundly shaped by the reality that we seem to only hear about it from women who have given it up. Hepola’s message thus adds to wider social demands that women remain vigilant and do not yield to the pleasures, such as they are, of taking a break from one’s obligations. Alcohol is legal and heavily marketed, including to women, but the public discourse surrounding drinking holds women to a higher standard of self-control. The necessary self-scrutiny is not about counting drinks but about motive. If you get drunk and something goes wrong, did you somehow bring it on yourself? If you want to take a break from your maternal responsibilities, does that mean you are a bad mother? In these ways, social disapproval of women’s intoxication forecloses opportunities to address women’s sexual vulnerability or to debate domestic dissatisfaction.

Works Cited

Crowley, John W. Drunkard’s Progress: Narratives of Addiction, Despair, and Recovery. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1999. Print.

Glaser, Gabrielle. Her Best-Kept Secret: Why Women Drink—And How They Can Regain Control. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013. Print.

Golden, Janet. Message in a Bottle: The Making of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Cambridge: Harvard UP 2005. Print.

Hepola, Sarah. Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget. New York: Grand Central P, 2015. Print.

Johnston, Ann Dowsett. Drink: The Intimate Relationship between Women and Alcohol. New York: Harper Wave, 2013. Print.

Knapp, Caroline. Drinking: A Love Story. New York: Dial P, 1996. Print.

Lerner, Barron H. One for the Road: Drunk Driving since 1900. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2011. Print.

Mothers against Drunk Driving (MADD). N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2016. <http://www.madd.org/>

Schmidt, Laura and Constance Weisner, “The Emergence of Problem-Drinking Women as a Special Population in Need of Treatment.” Recent Developments in Alcoholism, Volume 12: Women and Alcohol. Ed. Mark Galanter. New York: Plenum P, 1995. 309-34.

Scoblic, Sacha Z. Unwasted: My Lush Sobriety. New York: Citadel P, 2011.

Terry, Jennifer An American Obsession: Science, Medicine, and Homosexuality in Modern Society. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999. Print.

Travis, Trysh. The Language of the Heart: A Cultural History of the Recovery Movement from Alcoholics Anonymous to Oprah Winfrey. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2009. Print.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. “Women: Alcohol and Your Health: Special Populations & Co-Occurring Disorders.” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2016. <http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/special-po...>

Walton, Stuart. Out of It: A Cultural History of Intoxication. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2001. Print.

Figures

Fig. 1: Philip Morris. Virginia Slims: “You’ve come a long way baby,” 1989. Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. Stanford School of Medicine database. Web. 9 Feb. 2016. <http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st034.php&token1=fm_img0807.php&theme_file=fm_mt012.php&theme_name=Targeting%20Women&subtheme_name=Women%27s%20Liberation>

Fig. 2: Currier, Nathaniel. The drunkards progress. From the first glass to the grave. Lithograph. c1846. Library of Congress. Web. 9 Feb. 2016. <http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/91796265/>