Editor’s Postscript for NANO Special Issue 15: Twin Peaks: The Return, Walter Benjamin, and Jeffrey Epstein

by Matthew Lau

Published February 2020

“When you’re an artist, you pick up on certain things that are in the air.”

–David Lynch (quoted in Gilmore)

1.

Throughout the 1920s, as he began to turn away from a traditional academic career, the critic Walter Benjamin wrote a number of original, celebrated literary and cultural studies. In his overarching critique before this period, Benjamin scholars Peter Osborne and Mathew Charles argue Benjamin rejected Kant’s linear conception of historical progress and proposed key historical conjunctures and cultural touchstones as cyclically returning phenomena (“Walter Benjamin”). Bonapartism is a good example of such a key, recurring historical focal point. With Bonapartism, Marx sought to explain how “the class struggle … created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part” (“Preface”). The mediocrity in question for Marx was Napoleon’s nephew Louis Bonaparte, recurring as the French Emperor in a farcical coup of 1851 after Napoleon I’s tragic coup of 1799. As Marx himself remarked later, his analysis proved more significant than he anticipated. For while disastrous in many ways, Bonaparte’s regime surprised Marx with its staying power, ruling for two decades. And new Bonaparte-like mediocrities continue to exploit parochial resentments and false nostalgia for political gain, including Trump.

For Benjamin, such recurrent conjunctures are historical but also highly allegorical. Their allegorical dimension required the philosopher-critic to recognize and complete them with a decisive and possibly redemptive act of critical judgment (Osborne & Charles). Against this theoretical background, Benjamin honed a critical style that anticipated internet-based contemporary analysis on the cultural left. Benjamin’s aphoristic One-Way Street (1928) is in a way the prototype for a politicized social media profile. One-Way Street recognized the impact of mass communication systems on critical discourse in its terse and heterogeneous style and in its prescription that “significant literary effectiveness … must nurture the inconspicuous forms that fit its influence in active communities” (445).

Twin Peaks would have interested Benjamin as a cultural focal point not only for the way its creators, David Lynch and Mark Frost, invent a new genre from the remnants of familiar ones (especially police procedurals and soap operas), but for its historical conjuncture. The show’s surreal and mordantly satirical depiction of the American Dream as a nightmare began just after political scientist Francis Fukayama’s so-called “end of history,” when the Cold War defeat of communism made it appear that there was no alternative to a triumphant global capitalism, and history seemed to be ending like a Hollywood movie. Twin Peaks: The Return expands—it “sprawls” in Richard Martin’s term—out from the original’s post-Cold War conjuncture and calls America’s triumphalism more thoroughly into question by drawing on 1989’s nightmarish prehistory and its morbid future trajectory. Signified by the Trinity Test of a nuclear bomb, as regards its prehistory, the dawn of the Cold War becomes The Return’s origin story for its ironic nuclear family of BOB, Joudy, and Laura.

Meanwhile, the failed promise of capitalism in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis becomes the background radiation of The Return’s bleak contemporary world. Repeatedly in The Return, Lynch and Frost insightfully reveal that the post-2008 foreclosure crisis in the suburbs and exurbs never really ended. As Rob E. King and Richard Martin note in their articles in this special issue, the desolate, half-vacant subdivisions around Las Vegas are an important location in The Return, both for Agent Cooper’s reemergence into historical time from the extradimensional Black Lodge and for their documentation of the violence and despair of contemporary America. Here and elsewhere Twin Peaks: The Return notes the return of history itself as an ongoing catastrophe.

For both Lynch and Benjamin, history is cyclical as much as linear, and progress becomes akin to its opposites: regression and devolution. Progress is Benjamin’s ironic name for the chaotic storm blowing the wreckage of history away from paradise (“Theses on the Philosophy of History” 258). This same storm of progress turns the lights out in the foreclosed homes around Las Vegas and at the Palmer residence in the harrowing final moments of The Return. When Agent Cooper has finally returned Laura Palmer to life and to Twin Peaks, the primordial evil of Joudy and the predatory capitalism of the foreclosure crisis become one and the same.

2.

In Benjamin’s most celebrated literary essay of the 1920s, Goethe’s Elective Affinities (1925), described by its publisher Hugo von Hofmannsthal “as simply incomparable” (quoted in Rosen 139), Benjamin depicts the work of art, in his case Goethe’s novel, as “a burning funeral pyre.” The flame continues to burn and grow for Benjamin because the work survives its immediate moment of production and acquires new significance and meaning over the course of its later history. “The commentator,” analogous to a philologist, “stands before [the pyre] like a chemist” while the philosopher-critic, is “like an alchemist. Whereas, for the former, wood and ash remain the sole objects of his analysis, for the latter only the flame preserves an enigma: that of what is alive” (298). Benjamin’s dichotomy of commentary and critique correlates to Matt Miller’s discussion of access and fascination among viewers and critics of Twin Peaks in the introduction to this special issue. Commentary and critique in Benjamin’s sense, access and fascination in Miller’s, are fundamental to the articles in this special issue. The authors in this special issue recognize that critique without commentary becomes conjecture and speculation and that commentary without critique becomes trivial and pedantic. They recognize that access and fascination are mutually reinforcing and enriching for interpretation and also necessary for a work of art as complex and dark as Twin Peaks.

Benjamin’s funeral pyre is a particularly accurate metaphor and emblem for the core of Twin Peaks. The show is centered on the murder and ghostly persistence of Laura Palmer, the high school beauty queen raped by her own father while he was possessed by BOB—and then murdered by what appears to be BOB himself—after local elites had manipulated her into prostitution while she was still a minor and then discarded her after she became addicted to cocaine. Laura’s physical body, her image, and her spirit linger like the smoke from a funeral pyre throughout The Return with a renewed yet familiar intensity. These representations both are her and they are not her, at least not completely.

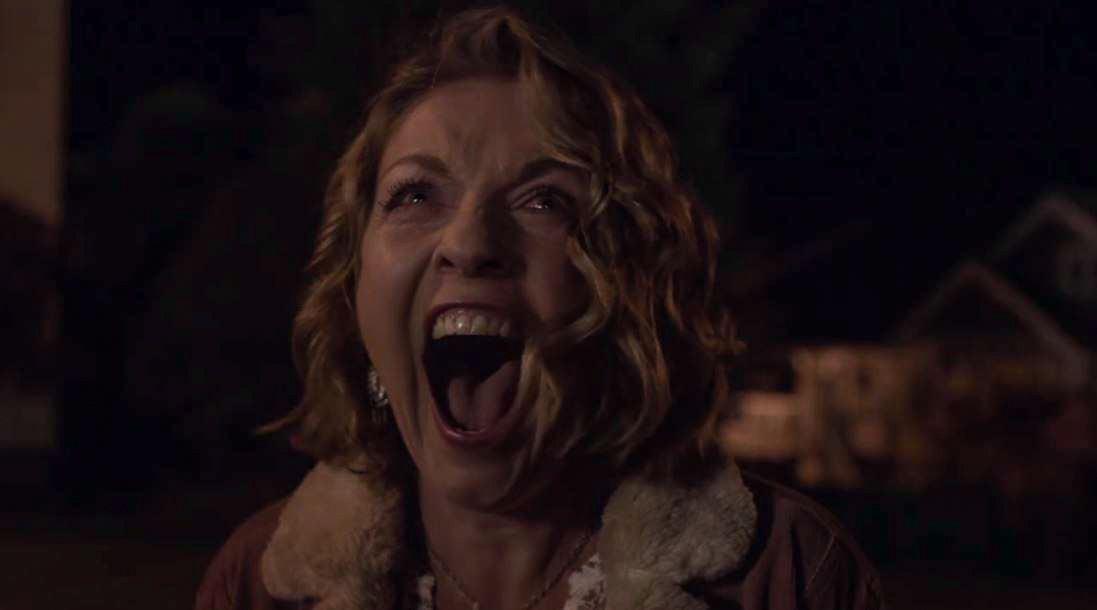

Then in a sublime instance of wish fulfillment by way of retroactive continuity, near the end of The Return, Cooper returns to the night of Laura’s murder and fundamentally alters the show’s timeline, taking Laura’s hand and seeming to lead her away from danger. She disappears from Cooper’s grasp but does not die. He hears her familiar blood curdling scream as she vanishes.

When he finds her again back in the present day of the show, it is her, and it is not her. She lives far away in Odessa, Texas and is called Carrie Page instead. Like Laura, Carrie’s dark side is catching up with her. A dead body is in her home. She must be responsible. Why else would she get in a car with Cooper, whom she does not recognize, with almost no questions asked? Arriving back in Twin Peaks with Cooper, Carrie does not recognize the house she grew up in; her mother is not there either; the new owners do not remember her family.

But then finally it is her; Carrie is Laura. Standing in the street outside her house, she hears her mother calling her voice in the distance and she screams in her familiar way, as the season ends with her home and her destiny going into foreclosure, as the power in her family’s home is suddenly cut. In the credits sequence Laura whispers something inaudible into Cooper’s ear back in the Red Room, their home for the 25 years between seasons that they seem to have returned to. This is The Return’s final return. Cycling back to its starting point, the Red Room again becomes their waiting room.

3.

If I were to propose a Benjamin-style critique as an addendum to this special issue, it would return us not to the Red Room, but to a location the new season neglects, One Eyed Jacks, the brothel near the Canadian border where Laura and other underage girls work as prostitutes after being recruited from the local department store’s perfume counter. The brothel is owned by Benjamin Horne, the richest man in town.

One Eyed Jack’s is the scene of bawdy laughs and melodramatic sentimentality in the original seasons, and few if any commentators seemed to notice its absence from The Return. But returning to it in the #metoo era and especially in light of the recent arrest, imprisonment, and death under mysterious circumstances of convicted pedophile and elite financier Jeffrey Epstein, one cannot help but see in One Eyed Jack’s a new political resonance.

The tone of the scenes at One Eyed Jack’s contrasts with the movie from the 1990s more widely discussed as an allegory for the ongoing Epstein scandal, Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick presents the sexual enslavement of women by the power elite as a glamourized and aestheticized spectacle with little sense of the women’s identities, let alone their interior lives. This affectless fantasy has the unintended effect of undermining Kubrick’s satire by dehumanizing the enslaved women. For Lynch and Frost, by contrast, the show’s scenes at One Eyed Jack’s are notable for their wicked and licentious humor, as when Benjamin Horne unwittingly attempts to seduce his own daughter. The humor here should not be mistaken for trivializing. Lynch’s dark comedy more accurately reflects the evil of the elite in the way Horne smugly and laughingly enjoys his own moral turpitude.

One detects here the irony of Lynchian surrealism coming much closer to historical reality than Kubrick’s austere realism. This suggests the affinity between Twin Peaks and the writings of Franz Kafka addressed by Karla Lončar’s contribution to this special issue. In Kafka, it is frequently the case that more nightmarish or abject the story becomes the more comical it becomes as well. In Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” while enraptured by his sister’s violin playing, Gregor Samsa finally becomes fully human emotionally, while at the same time an apple protrudes from his emaciated and filthy insect body. It is one of the most affecting passages in modern literature and one of its crueler jokes.

The same is true at One Eyed Jacks. The Epstein-like crimes of Twin Peaks’ power elite are more affecting not despite but because of gallows humor, familiar “daddy issues” from the Lynchian universe, and other mordant, subversive ironies. Such dark themes and black comedy accurately reflect the utter corruption of elites like Epstein, who laughingly enjoy their sadistic acts. Like post-Cold War America itself, the situation in Twin Peaks is catastrophic, but for the elites who are shielded from virtually any consequence, there is no need to take the catastrophe seriously.

The One Eyed Jacks subplot develops through the seduction and exploitation of Audrey Horne, the club owner’s teenaged daughter who seeks employment there as a way to help Agent Cooper gather information in order to solve Laura’s murder. Audrey’s loss of innocence, like Laura’s, much more closely resembles the circumstances of the many young women forced into sexual servitude by Jeffrey Epstein and his many accomplices than anything imagined by Kubrick. What happened to Epstein’s victims is a grotesque tragedy, of course. But it is also, as Lynch and Frost show in Twin Peaks, more like a sick joke after one comprehends the scale of Epstein’s crimes, his years of impunity, and his connections to political leaders and perhaps, as has been suggested, intelligence services. It is a conspiracy whose improbability and surrealism make it akin to the Twin Peaks universe.

As the show’s flame continues to burn, it will be Twin Peak’s critique of the power elite, especially their sexual exploitation of the young, along with other newly prescient aspects of the show referring to the horrifying moral rot at the heart of this late stage of capitalism, that will add the most combustible new fuel to its enigmatic fire, the expanding funeral pyre of Laura Palmer, the lost American girl next door. Indeed, as Lindsay Hallam points out in this special issue, the horror of Lynch’s art is also the source of its power because Lynch’s horror ultimately points to an underlying reality: the failure of the American Dream.

Works Cited

A Short History of “Retcon.” Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/retcon-history-and-meaning.

Benjamin, Walter. “Goethe’s Elective Affinities.” Selected Writings Vol. 1, 1913-1926. Belknap, 1996.

---. “One-Way Street.” Selected Writings Vol. 1, 1913-1926. Belknap, 1996.

---. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations. Schocken, 1986.

Brown, Julie K. “How a Future Trump Cabinet Member Gave a Serial Sex Abuser the Deal of a Lifetime.” Miami Herald, 28 Nov. 2018, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/article220097825.html.

Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History?” The National Interest, no. 16, 1989, pp. 3–18. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184?seq=1.

Gilmore, Mikal. “David Lynch and Trent Reznor: The Lost Boys.” Rolling Stone, 6 Mar. 1997, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/david-lynch-and-trent-reznor-the-lost-boys-62337/.

Kubrick, Stanley. Eyes Wide Shut. Warner, 1999. DVD.

Marx, Karl. “Preface to the Second Edition (1869).” 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte—Preface 1869, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/preface.htm.

Miller, Sam, and Harrison Fluss. “The 18th Brumaire of Donald J. Trump?” SocialistWorker.org, 5 Dec. 2016, http://socialistworker.org/2016/12/05/the-18th-brumaire-of-trump.

Osborne, Peter and Matthew Charles. “Walter Benjamin.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/benjamin/.

Rashbaum, William K., et al. “Jeffrey Epstein Dead in Suicide at Jail, Spurring Inquiries.” The New York Times, 10 Aug. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/10/nyregion/jeffrey-epstein-suicide.html.

Rosen, Charles. “The Ruins of Walter Benjamin.” Romantic Poets, Critics, and Other Madmen. Harvard UP, 1998.

Thomas, Landon. “Jeffrey Epstein: International Moneyman of Mystery.” New York Magazine, 28 Oct. 2002, http://nymag.com/nymetro/news/people/n_7912/.

“Twin Peaks: Seasons, Episodes, Cast, Characters—Official Series Site: Showtime.” sho.com, https://www.sho.com/twin-peaks.

Whalen, Andrew. “In ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ Stanley Kubrick Captured Horrors of Jeffrey Epstein Era.” Newsweek, 12 July 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/eyes-wide-shut-missing-footage-epstein-kubrick-death-1449108.