“I am dead yet I live”: Revealing the Enigma of Art in Twin Peaks: The Return

by Allister Mactaggart

Published February 2020

Abstract:

For fans, returning to Twin Peaks for a third season was always going to be wrought with intense speculation, anticipation, and, perhaps, a hint of trepidation. After all, a great deal has happened in the intervening quarter of a century, not least in the ways in which television is produced, distributed, and consumed. Would Twin Peaks be able to maintain its quirky and mysterious allure in the twenty-first century? Would David Lynch and Mark Frost be able to pull it off again? These questions were answered in a remarkable season which refused to provide a simple, nostalgic return to the town of Twin Peaks. Indeed, the season greatly expanded the geographical range and focus of inquiry, and aesthetic experimentation, to suggest that BOB’s evil has extended its criminal reach into a much wider orbit in the intervening period. Would FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper be able to offer us hope?

Introduction

When the first two seasons of Twin Peaks were broadcast in 1990-1991, keen fans were able to take advantage of the nascent form of Internet discussion groups to converse amongst themselves between episodes about the intriguing complexities of the series. In the intervening period the impact of social media has increased exponentially and has perhaps led us to expect new metaphors for understanding our current media ecology. However, as the social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson points out: “Perhaps less intuitively, the emergence of photography in the mid 1800s can help us understand the contemporary rise of social media” (1-2). As such, current philosophy and critical analyses are heavily dependent upon integrating ideas derived from older art forms and technological processes, such as photography, but also painting and the plastic arts, together with film and television, into our understanding of the new media landscape. Therefore, we have to bring into the fold both older insights alongside developing newer ones to try to come to some better understanding of where we are now and where we might be heading in the future. In this regard, I wish to suggest that Twin Peaks: The Return, the third season broadcast over 25 years after the end of Season 2 in 1991, provides a suitably interwoven and complex case study to consider important artistic, cultural, and critical continuities and changes over the intervening period, and how the resultant issues might affect us now and into the future. However, there is one photograph that haunts the three seasons to which I will argue we need to pay particular attention as it offers us a great insight into issues relating to art, life, and death in Twin Peaks and beyond.

Social Media

For avid viewers of the original two seasons, we probably knew in advance (and were secretly hoping) that returning to Twin Peaks was never going to be straightforwardly nostalgic and homely: how could it be? Having been left, in the final episode of season 2, with the image of Agent Cooper’s doppelgänger grinning maniacally after smashing his head into the bathroom mirror at the Great Northern Hotel and with BOB’s similarly evil grimace being reflected from the other side of the mirror, things were clearly going to be out of balance from the start. “It” (the evil that “men” do) was capable of getting into our houses now and running amok without Agent Cooper to protect us. Similarly, the beautifully elegiac ending of the subsequent prequel feature film, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), with Saintly Cooper and Laura cushioned within the curtained folds of the Red Room as an angel ascended beatifically in front of their (and our) eyes, suggested, even out of chronological time, that the opposing force of good was now outside our world and unable to intervene as evil Cooper, or Mr. C as we come to know him, has wreaked his havoc upon the expanded neo-liberal criminal underworld throughout North and South America in the intervening quarter of a century.

The message, “That gum you like is going to come back in style!,” simultaneously announced by David Lynch and Mark Frost on 3 October 2014 on Twitter, a source unavailable for viewers of the previous iterations of the program, excited those fans, such as myself, and signalled a hopeful return but within a very different media landscape (@mfrost11; @DAVID_LYNCH). While the original two seasons had benefitted from fan discussions over Usenet, particularly alt.tv.twinpeaks (Jenkins 53), would the new season fare so well in the very different media landscape of the twenty-first century? The resultant consternation produced when David Lynch decided to withdraw from the project citing lack of finance from Showtime, the subsidiary of CBS which financed it, followed by the febrile online campaign for him to return, signalled that Twin Peaks was still at the forefront of fan activity and benefitting from the increased connectivity provided by this new social media landscape. With the resultant announcement that a doubled number of parts were to be filmed, and knowing that Lynch would direct them all, we could wait with building anticipation, and perhaps some trepidation, in the intervening period up to 2017.

Sound and Vision

In Part 1 of the new season, the Giant as we knew him before, or the Fireman as we come to know him now, but cited in the credit list at the end of the Part as “Carel Struycken…(???????),” tells Cooper that “It all cannot be said aloud now.” So, there appears to be at least one mysterious secret being kept from us from the beginning, which raised the question as to whether we would ever get to hear “it” at all. But perhaps this is the secret whispered to Cooper by Laura Palmer (if it is her) in Part 2, after she kisses him and then is violently ejected from the Red Room by some malevolently powerful force. As she whispers in his ear Cooper’s face registers some disquiet as he realises the impact of what she’s saying. Prior to this exchange she had said to him, “I ... am dead ... yet I live.” Following which, she pulled off her face to reveal an intense white glow behind the mask of her facial features.

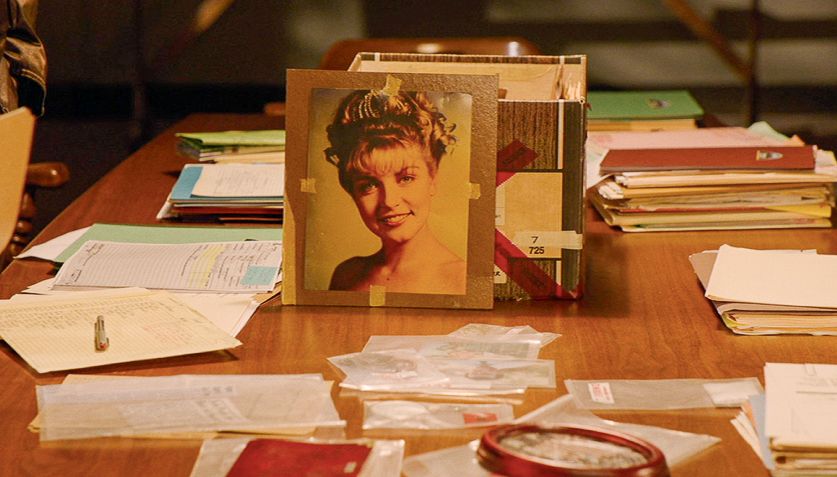

The entire three seasons have circled around the trauma of Laura’s death and the mismatch between her public face, exemplified by her photograph as a high school homecoming queen, and knowledge of the horrors of her private life of sexual abuse, drug taking, and sexually dangerous situations in which she found herself. Even accounting for the growing number of other murders and deaths that have been presented on screen over the three seasons, it is this still photograph to which we return repeatedly and which calls out for our special attention.

Photography

This iconic photograph significantly reappears at key moments throughout The Return. Starting in Part 1 with the photograph in pride of place within the medal cabinet of the town’s high school from the original season, it is pictured again and again as a redolent image frozen in time, yet haunting all with its smiling presence of a life cut tragically short. Susan Sontag wrote that: “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed” (4). One of the definitions of appropriate is “to set apart for a purpose, assign (formal or archaic)” (Chambers 75). The photograph of Laura is indeed somehow set apart—it cannot be simply integrated into the narrative. In a similar manner to how Laura Mulvey argues that the role of woman in classical Hollywood film is to delay or impede the narrative trajectory, “to freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation” (19), this photograph (in my reading at least) instigates a similar pause or reflection, one which seemingly transfixes, saddens, or angers its viewers (as we’ll discuss shortly). Again, as Sontag points out: “A photograph is both a pseudo-presence and a token of absence” (16). Constantly present but signifying an aching absence within Twin Peaks, and reinforced by the uncanny appearances of her cousin Maddy Ferguson, and now a middle-aged Laura Palmer/Carrie Page (all played by Sheryl Lee) in The Return, “she” haunts, or taunts, all those who seek to uncover the secrets of her life and death and how it all went so wrong. Even the afterlife, or waiting room, as we have seen, is clearly not an entirely comfortable place to inhabit and there seems to be little prospect of ever getting out unscathed, or moving on to a more resolved location.

When, in Part 4 of season three, one of Laura’s ex-boyfriends, Bobby Briggs (Dana Ashbrook), now a Deputy within the town’s law enforcement agency rather than the young tearaway he was in the original series, sees the photograph in the conference room of the Twin Peaks Sheriff’s Department, his face contorts into the painfully tearful emotional response which Lynch has presented so many of his characters with throughout his filmography, and states: “Man, brings back some memories.” Indeed, those images may be an effort to affect viewers, to reflect as signifiers the changes in the lives of both the viewing audience and the characters in Twin Peaks, several of whom have died in the intervening period but whose images reappear on the screen: for example, BOB (Frank Silva), or Major Garland Briggs (Don S. Davis); or reminders of those who have died since season 3 was shown, as in the following: FBI Agent Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer), Carl Rodd (Harry Dean Stanton), Norma Jennings (Peggy Lipton), and Sheriff Frank Truman (Robert Forster). The Return ’s depiction of the dying Margaret Lanterman’s, aka the Log Lady (Catherine E. Coulson), telephone messages to Deputy Chief Tommy “Hawk” Hill (Michael Horse) perhaps being the most poignant of all, although even here creativity seems to win out over pathos. Part 1 is dedicated “In Memory of Catherine Coulson,” who plays the Log Lady, and Part 15 “In Memory of Margaret Lanterman,” the character of the Log Lady—both are accorded the same level of acknowledgment.

Thus, art, in its many forms, keeps alive ideas and thoughts, images and memories and, similar to Lynch’s belief in Transcendental Meditation and Eastern philosophy, art can provide an afterlife which The Return acknowledges. This can be seen in the way that we return to the world we’d left behind over a quarter of a century ago, where linear time has aged its inhabitants and viewers, but where non-chronological time provides for a reflection upon art (in whatever technological medium is used) and its place in society.

For those theorists of photography and television of an earlier generation, there was a distinct difference between the two mediums. For instance, Sontag remarks that “Television is a stream of underselected images, each of which cancels its predecessor” (18). Similarly, Raymond Williams identified “flow” as a fundamental component of multi-channel television as he first came across it in the United States (86). However, it might be argued that such levels of analysis are less applicable now due to the changes in television distribution and viewing patterns opened up by new viewing platforms, such as streaming and the impact of binge watching. Yet, there’s more to this in relation to season 3 than a shift away from the concept of “flow” to some other more relevant theoretical level of analysis for our current times. For has not Lynch always created his film and television work by producing a series of individually distinct and painterly-like images? Indeed, Lynch has constantly sought to choose images which hold their individual forcefield within the overall stream of imagery in the narrative trajectory. Each image, like one of Lynch’s paintings or other graphic work, can stand alone as well as being part of a longer narrative structure, linear or Möbius strip-like, as the case demands. The gaps between images or frames are somewhat similar to the stilted speech patterns in Lynch’s work, where sentences spoken appear like non-sequiturs rather than communicative utterances. In The Return, for example, Sam Colby’s (Benjamin Rosenfield) short, staccato sentences exchanged with Tracey (Madeline Zima), as they play out their sexually charged way into the fateful room with the glass box in New York, like many of the sentences spoken by Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) and the detectives in Lost Highway (1997), signify the failure of language to communicate clearly; something is lost in the ether, and that this something has been central to all of Lynch’s art practice over many decades. Words may fail but experiences may result in a deeper felt understanding. From The Alphabet (1968) onwards, Lynch’s distrust of language makes itself felt in the multi-sensory folds of his audio-visual work, where feelings and emotions carry a greater weight—the weight that words do not seem to be capable of embodying on their own. Or, perhaps it is suggested that words can fatally disembody.

Moving Paintings

In his memoir Room to Dream, Lynch remarks about only having a television in his house when he was in the third grade and suggests that: “Television did what the Internet is doing more of now: It homogenized everything” (22). Interestingly, he remembers watching little television apart from Perry Mason, and perhaps the golden seed for his television production work was sown there. Elsewhere, Lynch has talked about the difficulties of watching films on television: “On TV the sound suffers and the impact suffers. With just a flick of the eye or turn of the head, you see the TV stand, you see the rug, you see some little piece of paper with writing on it, or a strange toaster or something. You’re out of the picture in a second” (Lynch 2005, 175). And yet there’s a grudging acknowledgement of the (artistic) necessity to take on board this new media landscape. Originally, Lynch set himself against digital technology but came to appreciate it when making Inland Empire (2006). He has talked about the possibility of there being no movie theaters left in the future and that “the majority of people will see films on their computers or their phones” (Lynch and McKenna 349). Remember the “Get real” diatribe against watching films on phones (Lynch 2007)? Yet, similar to Inland Empire, The Return was shot digitally but Lynch can still remark about digital (in relation to Inland Empire) that:

As good as it is, digital seems brittle compared with analog, which is thick and pure and has a smooth power. It’s like the difference between oil paint and acrylic paint. Oil is heavier and I always want to go with the heavy one, but there are things you can do with acrylic that you can’t do with oil. (Lynch and McKenna 435)

These analogies between film and television technologies and painting are central to Lynch’s vision of each art form and form of art practice. Lynch’s work has increasingly become a total artwork (Gesamtkunstwerk) in the Wagnerian sense of the term. However, at one time, early in his career, Lynch purposely kept his painting and film work separate so that it would not to be regarded as “Celebrity Painting” (Lynch 2005, 28). Now, however, the links are more clearly known about and integrated in various, multi-faceted ways. The influences of the work of other artists, such as Edward Hopper and Francis Bacon are keenly felt throughout The Return. For example, the glass box in New York from which Sam and Tracey are so violently and indecently killed in the midst of their illicit coupling—the resulting images of their bloodied and decapitated bodies takes Bacon’s work a step further than even he went. Noriko Miyakawa, the assistant editor and post-production coordinator on Inland Empire, and assistant editor on Twin Peaks: The Return, remarks that: “The people who work for him have to be skilled, but basically we’re like his brushes” (Lynch and McKenna 447).

In his catalogue essay for the exhibition, David Lynch: The Unified Field, held at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 2014-15, the art school where Lynch had briefly attended as a student in the mid-1960s, Robert Cozzolino writes:

Although the opposite has been asserted, Lynch is an artist who happens to make film as part of his expression. His identity as an artist is key to his work. His films are dependent on, flow from, and are inseparable from his identity as a visual artist; they are a painter’s films, concerned with issues that arise from his sensitivity to composition, texture, formal relationships, and how subjects are enhanced by their presentation in a particular style. (14-15)

This artistic, painterly sensitivity and approach can also be seen in the manner in which Lynch respects his audience throughout his work; he does not condescend or simplify, and this can be observed in the ways in which he doesn’t provide easy, generic answers to the mysteries of his art, whether paintings, photographs, film, television, etc. The work invites a deep form of active engagement from its viewers—its mysteries are thus kept alive rather than being closed down. As Lynch has said previously, knowing how the baby in Eraserhead (1977) was made would not add to our knowledge, indeed it may completely eradicate the mystery (Lynch 2005, 78). Similarly, The Return, by offering an origin myth for BOB in Part 8, could have provided a too simple explanation for “his” entry into the world. Yet, by tying this into the Trinity atomic bomb test in 1945 and our knowledge of the resultant horrors produced by the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and linking this to the incestuous horrors later inflicted upon fictional small-town America, Lynch and Frost suggest that these events are connected and not separate entities. The formal and aesthetic complexities of this Part, as critics have noted (Metz), almost allows it to act as a standalone section, as a separate digital art experiment, similar to the ones presented on his website or compiled on the DVD Dynamic: 01: The Best of DavidLynch.com (2006). When the Woodsman (Robert Broski) attacks the radio station towards the end of that Part, it is revealing to note in the DVD extra of the filming of this scene that Lynch is shown asking for the shots to be kept very dark, because that was what it was like in the 1950s when he was growing up without the benefit of electric street lights (Jason S.)

In the radio station scene Lynch directly uses a painting source—Edward Hopper’s Office at Night (1940)—and puts the viewer into the position of the Woodsman, as we see the woman move, seemingly without being able to stop herself, towards her demise. In an analysis of Hopper’s work, the art historian Margaret Iversen remarks upon two unusual features in Hopper’s paintings: the “film-still quality,” which is partly to do with “the suspended narrative” and the unusual “‘camera angles’” (421) which, she suggests, produce a “blind field” by cropping and angles, to suggest that what we see in the frame asks us to reflect upon what is outside it but elicits our desire through its absence and which “infiltrates the whole composition” (422). This is also what Lynch does throughout The Return (and elsewhere) where the frame of the image both contains significant details but, at one and the same time, elicits our desire for what is elsewhere and to where we hope we’ll be taken.

Relating this to the origin myth of BOB, Mark Frost’s paratext, Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier (2017), written as a series of internal FBI reports by Special Agent Tamara Preston, suggests that the girl we see in Part 8 unknowingly ingesting the mutant creature is a young Sarah Palmer, who then carries the seeds of that distorted, unnatural evil with her into her adult life. So, while we had seen Laura’s father, Leland Palmer, accidently but tellingly spilling blood onto the homecoming queen photograph of Laura in season one, episode two; at the end of Part 17 we are presented with very disturbing images of Sarah Palmer attacking the same photograph of Laura, seeking to destroy that iconic image. The editing and sounds here are instructive—stilted and jarring—coupled with glitches and seemingly playing backwards, as Sarah appears, from a parallax position, to be trying to undo Cooper’s attempts in that Part to bring Laura home and back to life, and thus avoid her murder. Yet the photograph remains unbroken however much Sarah violently tries to destroy it—somehow it remains intact, smiling back at her failed, “impotent” attempts to eradicate “her.” So, while the (fictional) character of Laura might have been killed, her representation lives on and smiles back enigmatically at those who seek to uncover “her” mystery—the mystery seemingly behind the mask.

Yet in the dialectic between the still image and narrative momentum it must be borne in mind that the latter is always partial, that narratives can deal with certain questions we may have but that they cannot answer everything that affects us. The television theorist Milly Buonanno has remarked that:

The delay and removal of the ending are the prerogative of the serial, which adopts the linear and evolutionary concept of time but manipulates it—in particular in the case of the open serial—by deferring or denying its irreversible progress towards a terminal point of no return. (131)

That point of no return, which television serials, and narratives in general, seek to delay, is a symbolic representation of death (130). So, when Cooper (or is he Richard) eventually tracks down Carrie Page to take her back to Twin Peaks, the audience might wonder whether a final resolution could be provided for us. Initially, indeed, the “Palmer” household looks as it has always done from the outside in this season. But, upon finding that it is owned and occupied by Alice Tremond (Mary Reber, the current owner of the actual house) and bought from a Mrs. Chalfont, Cooper and Carrie (and the audience) are at a loss. Compounding and confusing names from the previous seasons with no explanation, we are left here in a decidedly unsettled state. Subsequently standing in the road, Cooper wonders what year it is, then Carrie hears the muffled sound of Sarah Palmer calling out “Laura” from within the house and screams a painful cry of recognition, resulting from which the light bulbs appear to explode in the house plunging it into darkness. She’d also screamed earlier in Part 17 when she’d seen Cooper in the woods the night she disappeared, as he tried to go back in time to undo her murder. Yet, as Todd McGowan (2018) has pointed out, Cooper is actually part of the problem and not the solution. However much he tries to unravel the traumatic knot of Laura’s pitiful life, she cannot be put back whole again; there is something missing, and it is trauma that constitutes the subject. But that something missing or that which wounds, that trauma or punctum to use Barthes’s term, does not appear to be immediately present in the homecoming queen photograph. In the official portrait, everything appears to be correctly in place; perhaps that is why it causes such affect and consternation, by signifying a wholeness that has been violently terminated and which is at odds with her traumatic private life, but which cannot, however much people try to, be eradicated or put right. Or perhaps the punctum is actually her seemingly innocent enigmatic smile which confronts and confounds all those who look upon her.

Returning now to the end of Part 18, after Carrie’s scream, the screen goes to black and then slowly reveals the image of Laura whispering into Cooper’s ear in the Red Room as the credits are played against melancholic background accompanying sounds. Is this not actually an appropriate ending to where we are now, again; out of time and out of place, with Laura both seemingly dead yet alive? The Fireman told us in Part 1, “It all cannot be said aloud now.” Should we ever have expected Lynch and Frost to resolve fully the complexities of Laura’s (and our) life and death, of questions of evil, with a clear, causal answer? Instead, is it not more fitting for us to be left to reflect upon what we’ve seen, heard, and experienced? As a long-form, slow-moving narrative painting, Twin Peaks: The Return provides us with much to reflect upon, and with a crucial enigma to ponder: Will it ever prove possible to say “it” all aloud?

Conclusion

In a review of season 3, Denis Lim has remarked that: “The original Twin Peaks revolved around a single dead girl, but in The Return, populated with an abundance of lined faces and frail bodies, death is everywhere” (111). As a treatise upon time and ageing, this is clearly apparent over a quarter of a century since the end of season 2. However, there is also an uncanny aspect to death in The Return that links it back to the previous two seasons as well as with various art forms over millennia. As André Bazin (2005) pointed out, the plastic arts have always “embalmed” the dead, from the time of Egyptian mummification onwards.

In a most perceptive essay John Berger addresses the riddle of why the earliest painted portraits that have survived, known as the Fayum portraits, made in Egypt from the first to third century BCE, look so contemporary and touch us in the present. These painted images were not made to be seen but “to be attached to the mummy of the person portrayed” (8), and put with the bodies in necropolises and thus “images destined to be buried, without a visible future” (9). These full-face or three-quarters full-face images presented a very different visual appearance to the earlier prevailing side profile and Berger argues that “all of them are as frontal as pictures from a photo-mat,” and further that, “Facing them, we still feel something of the unexpectedness of that frontality” (9).

Similarly, Laura’s photograph, as a contemporary example of a frontal death mask, brings me up short each time it’s experienced. Like every photograph, it stops the stream of life, and the narrative trajectory of Twin Peaks, in its “funereal immobility” (Barthes 6). As Bazin pointed out, in relation to the origins of painting and sculpture in ancient Egypt, these practices sought to satisfy “a basic psychological need ... for death is but the victory of time” (9). Likewise, in the contemporary saturated social media world, Jurgenson argues that “Photos, like all documents, are nostalgic in that they embalm their subjects—a stilling sadness that kills what it attempts to save out of fear of losing it, a fear of death” (26).

Twin Peaks: The Return provides us with many images of death, both diegetically in the narrative flow, but also in the realisation of ageing and death in cast members (and viewers) over the period since the original two seasons. Partly this may reflect to some degree Lynch (and Frost’s?) adherence to Eastern philosophical approaches to death and reincarnation, but it also demonstrates the ways in which art, photography and media more generally are implicated in a continuing but impossible desire to capture life and keep death at bay. This desire to seek in some way to overcome time relates back to the origins of painting and sculpture as Bazin and Berger so perceptively pointed out. It also continues into the present, both in Twin Peaks and the contemporary saturated social media world as Jurgenson analyses. The still photograph appears to occupy a privileged place in contemporary reflections upon art, death, and time, with Laura’s homecoming queen image encapsulating a great deal about what is uniquely uncanny about photography. However much Special Agent Dale Cooper tries to turn the clock back, to undo Laura’s murder, he cannot. Life streams on, but the still, silent photograph of Laura which refuses to say anything aloud, fixes her in time and place, and reminds us as viewers of the impossibility of ever returning to our first home as we wend our way to our final resting place, leaving art as a trace, or snapshot, that we were once here.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. Translated by Richard Howard, Vintage, 1993.

Bazin, André. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” What is Cinema? Vol.1. Translated by Hugh Gray, U of California P, 2005, pp. 9-16.

Berger, John. “The Fayum Portrait Painters (1st -3rd century).” Portraits: John Berger on Artists, edited by Tom Overton, Verso, 2015, pp. 7-11.

Buonanno, Milly. The Age of Television: Experience and Theories. Translated by Jennifer Radice, Intellect, 2008.

Chambers. The Chambers Dictionary. Harrap, 1998.

Cozzolino, Robert. David Lynch: The Unified Field. U of California P, 2014.

@DAVID_LYNCH. “Dear Twitter Friends: That gum you like is going to come back in style! 3 Oct 2014.” https://twitter.com/david_lynch/status/518060411690569730?lang=en.

Frost, Mark. Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier. Macmillan, 2017.

Hopper, Edward. Office at Night. 1940, Oil on canvas, 22 x 25 in., Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Inland Empire. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Laura Dern, Jeremy Irons, Harry Dean Stanton, Justin Theroux, Karolina Gruszka, Grace Zabriskie et al ., StudioCanal, Camerimage Festival, Fundacja Kultury, Asymmetrical Productions, Absurdia, distributed by 518 Media, 2006.

Iversen, Margaret. “In the Blind Field: Hopper and the Uncanny.” Art History, vol. 21, no. 3, 1998, pp. 409-429.

Jason, S. “The Number of Completion.” Impressions: A Journey Behind the Scenes of Twin Peaks. Twin Peaks: A Limited Event Series, DVD Extra, Disc 8, 2017.

Jenkins, Henry. “‘Do You Enjoy Making the Rest of Us Feel Stupid?’: alt.tv.twinpeaks, the Trickster Author and Viewer Mastery.” Full of Secrets: Critical Approaches to “Twin Peaks,” edited by David Lavery, Wayne State UP, 1995, pp. 51-69.

Jurgenson, Nathan. The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media. Verso, 2019.

Lim, Dennis, “Memento Mori.” Artforum International, vol. 56, issue 3, 2017. p. 111.

Lost Highway. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette, Balthazar Getty, Robert Blake, Robert Loggia, Richard Pryor, Jack Nance, Natasha Gregson Wagner, Gary Bushey, Henry Rollins, and Lucy Butler, Ciby 2000, Asymmetrical Productions, 1997.

Lynch, David. Lynch on Lynch (revised edition), edited by Chris Rodley, Faber and Faber, 2005.

---. Dynamic:01. The Best of DavidLynch.com. Absurda, 2006.

---. “On watching movies on phones.” 2007. Uploaded to YouTube by Britney Gilbert, 4 Jan. 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wKiIroiCvZ0&fmt=18.

Lynch, David and Kristine McKenna. Room to Dream. Canongate, 2018.

McGowan, Todd. “Waiting for Agent Cooper: The Ends of Fantasy in Twin Peaks: The Return.” Freud/Lynch: Behind the Curtain Conference, London, 26 May 2018.

@mfrost11. “Dear Twitter Friends: That gum you like is going to come back in style.” 3 Oct. 2014, https://twitter.com/mfrost11/status/518060486156230656?lang=en.

Metz, Walter. “The Atomic Gambit of Twin Peaks: The Return.” Film Criticism, vol. 41, issue 3: Reviews, Fall 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/fc.13761232.0041.324.

Mulvey, Laura. Visual and Other Pleasures. Macmillan, 1989.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Penguin, 1979.

The Alphabet. Directed by David Lynch, performance by Peggy Reavey, 1968.

Twin Peaks. Directed by David Lynch (episodes 1.1, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 2.7, 2.22). Performances by Kyle MacLachlan, Sheryl Lee, Piper Laurie, Peggy Lipton, Jack Nance, Joan Chen, Richard Beymer, Ray Wise, Frank Silva, Russ Tamblyn, Sherilyn Fenn et al., Lynch/Frost Productions, ABC, 1990-1991.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Sheryl Lee, Ray Wise, Mädchen Amick, Dana Ashbrook, Phoebe Augustine, David Bowie, Grace Zabriskie, Harry Dean Stanton, Kyle MacLauchlan, et al., Twin Peaks Productions, Ciby 2000, New Line Cinema, 1992.

Twin Peaks: The Return. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Kyle MacLachlan, Sheryl Lee, Michael Horse, Chrysta Bell, Miguel Ferrer, David Lynch, Robert Forster, Kimmy Robertson, Naomi Watts, Laura Dern, et al, Showtime, 2017.

Williams, Raymond. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. Routledge, 2003.