“The Past Dictates the Future”: Epistemic Ambivalence and the Compromised Ethics of Complicity in Twin Peaks: The Return and Fire Walk with Me

by Joshua Jones

Published February 2020

Abstract:

In this paper I explore questions of epistemology and complicity in Twin Peaks: The Return with reference to the original series and to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. I characterize these works as auto-exegetical texts (texts that critically read themselves), and I introduce the notion of epistemic ambivalence to describe how they proffer the possibility of teleological resolution while deliberately failing to provide enough information to realize that possibility. I examine how epistemic ambivalence is frequently deployed around questions of complicity with and culpability for evil, with the effect that the desire for certain knowledge and meaning is problematized by its connection to a masculinized desire for mastery. I argue that epistemic ambivalence is not just an important theme but is an integral characteristic of The Return’s ambivalently complicit story of violence and objectification. I reach two main conclusions: first, that the foregrounding of Laura’s pain in both Fire Walk with Me and The Return demands that audiences address and reflect upon our own complicity with the violence inflicted upon her; and second, that while there may be value in remaining attached to the desire for certain knowledge and to the dualistic conceptions of good and evil deployed ambiguously throughout Twin Peaks, there is perhaps more ethical and critical value to be found in exploring how these works engage the ambivalence such attachment engenders.

Twin Peaks has from the start tended to be ambivalent about knowledge in the form of narrative revelation and as a source of closure. David Lynch famously never wanted to reveal the killer of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), whose murder functioned as our entry point into the strange world of Twin Peaks, due to his belief that “once that was solved, the murder of Laura Palmer, it [the show] was over” (quoted in Robinson). For Lynch, “closure” is, in a pejorative sense, “absurd” (Weinstein). Nevertheless, as his uncharacteristically helpful “10 Clues to Unlocking”—opening up, not necessarily solving—his 2001 film Mulholland Drive suggest, the absence of closure should not be taken to obviate the search for meaning. Laura’s killer, of course, was revealed in season two, under pressure from network executives, to be her father, Leland Palmer (Ray Wise). While this revelation provided an answer of sorts to the show’s principal mystery, the question of whether Leland or BOB (Frank Silva) was ultimately culpable for Laura’s murder—or indeed to what extent they could even be separated from one another—remained ambiguous. Likewise, who or what BOB actually was, and how he entered the human world of the show’s diegesis, was left unresolved, with FBI Agent Albert Rosenfield (Miguel Ferrer) speculating that BOB is perhaps just “the evil that men do” (S02E09).

Albert’s interpretation of the show’s events is one example among many of not only viewers but characters themselves trying to figure out the meaning of what they’re witnessing.

Due to this incorporation of self-questioning into its diegesis, Twin Peaks can be called an “auto-exegetical text”—that is, a text that “critically reads itself” (Clute and Edwards 281) in such a way that its own gaps and incoherences, and the potential impossibility of ever fully resolving them into clear meaning, become active and important aspects of the narrative. Auto-exegesis also serves in Twin Peaks to incorporate the viewer’s desire for answers into the narrative. By drawing attention to the show’s own refusal to provide clear answers to the questions it raises and highlighting the lack of closure produced by this refusal, viewers are invited to interrogate their desire for closure. According to Todd McGowan, the “great achievement” of Lynch’s films resides in how they “implicate” the viewer “in their very structure,” forcing viewers to “become aware” of how the films themselves “[take] into account the spectator’s desire” (2). In this essay, I explore how Twin Peaks: The Return implicates both itself as an ongoing narrative and the viewer’s concomitant desire for closure in what I describe as the reobjectification of Laura Palmer. In doing so, I suggest, it performs, and produces in viewers, epistemic ambivalence, which I define as a feeling or condition in which a person knows that knowledge—as a form of certainty or mastery—may not be possible or even desirable, and yet remains unable to fully detach from the desire for such knowledge.

As exemplified by the revelation of Leland as Laura’s murderer and the subsequent refusal to spell out for viewers clear answers to the implications of this revelation, Twin Peaks self-consciously proffers the possibility of closure while deliberately failing to provide enough information to fully realize that possibility, thus calling into question the necessity—at the same time as keeping open the possibility—of such resolution. To this extent, Twin Peaks itself—as an auto-exegetical text—can be said to occupy, and in doing so encourage viewers to occupy, what Stuart Hall calls the “negotiated” viewing position: a viewing position that is at once “adaptive and oppositional” to the hegemonic cultural elements and assumptions encoded into texts (in this case, expectations for closure, and the normativity of violence against women as a televisual trope), accepting their presence while interpreting the text in ways that “do not follow inevitably” from or in service to those hegemonic elements (136-137). While amenable, given the show’s ambiguity, to polysemous readings—an interpretive position in which viewers insert their own meanings into texts (Morley) —Twin Peaks’ own adoption of a negotiated position seems geared not toward an interpretive response in which “anything goes,” but instead toward compelling from viewers trenchant and critical immersion in the ambivalences that can arise from negotiated viewing positions. With Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me ( FWWM) and its freedom from what was then the constraints of network television, epistemic ambivalence in particular becomes increasingly integral to the narrative functioning of the Peaksverse as a whole. Furthermore, desire for and belief in the possibility of closure as a form of unambivalent knowledge becomes connected to the gendered violence FWWM itself depicts, particularly that which is inflicted upon Laura. In doing so, FWWM performs what I characterize as a compromised ethics of complicity with gendered epistemic violence. In response to Lynch’s own claim that FWWM is “very much important” (Hibberd) for understanding The Return and to its emphasis that “the past dictates the future” (S03E17), I argue that The Return itself critically (re)reads and (re)incorporates into its narrative the epistemic ambivalence introduced by the original series and expanded upon in FWWM. I conclude by suggesting that, despite reobjectifying Laura Palmer, The Return mitigates against the violence of doing so by returning Laura’s trauma to the foreground, by shifting viewer identification away from Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) to Laura herself, and by encouraging viewers to renegotiate their relationship to and investment in the desire for closure and epistemic certainty.

In the original Twin Peaks, Laura Palmer was not so much a character as she was a plot device, operating as a structuring absence from which the show’s various erratic threads could spiral out and feed back upon themselves. The true protagonist of the show was Dale Cooper, whose search for meaningful answers reflected viewer desire for the same (as Lynch has stated, “I believe we are all detectives” [Rodley 168]). When it was announced, following the show’s cancellation and season two’s vertiginous cliffhanger, that Lynch would be directing a Twin Peaks movie, Laura’s story was largely forgotten by many fans, replaced by desire for resolution to Cooper’s arc. As such, FWWM was felt at the time by numerous viewers to be dissatisfying. Rather than continuing where the series left off and revealing what happened to Cooper, FWWM instead served as a prequel detailing Laura’s final seven days of life, announcing bluntly in its opening scene its rejection of viewer expectations for closure via an axe destroying a television set.

In shifting viewer focus—if not necessarily viewer identification—from Cooper to Laura, FWWM provides an implicit and yet stringent critique of the desire for narrative closure and certainty that, for Lynch, destroyed the original series by “snip[ping] its head off” (Stern). In the show, Laura was, as one critic disapprovingly notes, “a disparate collection of parts” (Blake 237)—an impossible composite of contradictory cinematic tropes representing cisgender femininity in the eyes of men. To this extent, it can be argued that she was a product of what Laura Mulvey terms the “male gaze,” in which women on film are represented as “bearers” rather than “makers” of meaning (Mulvey 15)—prompting, in the case of Twin Peaks, a desire to know that has less to do with Laura herself than with the desire to know via Laura, as an object capable of providing fuller knowledge of the show’s mysteries. (Laura herself expresses a similar sentiment in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer: “My life is what the other person in the room wants it to be” [167]). While raising the possibility that the hidden meanings Laura bears may be revealed by granting viewers the access they were denied by the series to her living body, FWWM instead depicts—in a manner that is, in Slavoj Žižek’s words, “both horrific and enjoyable” (ix)—Laura’s tragic attempt to inhabit the roles into and by which she has been condemned and constrained, in the process subversively connecting desire for knowledge as closure via Laura to a male gaze that, like BOB, seeks to penetrate Laura’s interiority and consume the “secrets” of which she is “full” (S01E02). FWWM shows, in painful, lingering, and unflinching detail her ultimate consumption by the world that shaped her. The camera tracks her downfall relentlessly at every step, to the extent that the viewer who fails to look away is forced into an unsettling complicity with the events that are unfolding. These events culminate in Laura choosing to die rather than become possessed by BOB, a final act of agency that refuses both him and us, disallowing viewers to ultimately know the secrets she supposedly contains.

Laura’s choice represents a resolution of sorts, albeit a negative resolution: it allows viewers to know that there are things they cannot or will not know and thus effects upon them a state of epistemic ambivalence. At the same time, the scene critiques the violence inherent in the desire to know, with the force of its compelling visual onslaught in a sense punishing viewers for attempting to unravel its mysteries in the first place. The fact that the compelling object from which knowledge is violently sought—both the film and Laura as character within it—also punishes viewers for seeking that knowledge highlights the ambivalence of the film’s own position in negotiating the ethical implications it raises regarding the desire to know: the film’s existence as an object designed for interpretation makes it just as complicit as its viewers. Is it attempting to justify or even absolve itself for what its unclear referent has depicted? Does the complicity the film both compels and exhibits serve as an escape clause, a pseudo-critical reproduction of the violence of a male gaze designed to shock and titillate? Perhaps, but whether or not this may be the case, in shifting viewer focus from detective to victim FWWM “manipulates” the tropes that constitute the Laura of the original series in order to “convey the fracturing experience of trauma” and to reframe Laura’s “double life” as not a source of mystery but a “symptom” of her trauma (Hallam 15, 27). Furthermore, the film’s narrative allows Laura to die on something like her own terms, rather than those imposed upon her by the revelation of her murderer in service of narrative closure. As Part 17 of The Return reveals, “the past dictates the future,” and as Lynch himself has stated, FWWM came with “baggage,” the “dictates” of which “it had to follow” (Rodley 190). To this extent, FWWM is forced and forces viewers to confront the trauma inflicted upon Laura within the diegesis by Leland/BOB, the violent implications of the film’s and viewers’ gendered use of Laura as a bearer of meaning, and the original show’s violent imposition—reflecting viewer desire—of narrative closure. Lynch has also stated that “closure … gives you an excuse to forget you’ve seen the damn thing” (Weinstein). Rather than leaving Laura behind again to become forgotten in the symbolic death that is closure, FWWM situates itself and viewers in a position of complicity with the violence—emotional, physical, and epistemic—that has been inflicted upon her. In doing so, it suggests that the desire for knowledge as unambivalent closure does violence to its objects. It encourages viewers not to attempt to superficially resolve the dilemmas of complicity but to reevaluate and renegotiate their investment in such potentially violent desire from a position of epistemic ambivalence and to begin to derive from occupying that compromised position a more ethical approach to knowing that is not—or is at least less—conditional upon doing violence to its objects.

The final scene of FWWM supports this reading while also cementing the film’s “very much important” role in understanding The Return. According to Allister Mactaggart, at the end of FWWM Laura was, in a sense, safe. Following her death, Laura is shown to be with Cooper—who has been largely absent from the narrative and, when participant, ineffective, such as when he warns Laura not to take the Owl Ring—while flanked by angels in the ambiguous space of the Red Room.

The scene is temporally suspended from the events of both the original series and the film, concluding the latter but preceding the former in a way that makes no narrative sense. Instead, it serves as a “space for . . . contemplation” that, while providing no real closure, permits at least for “catharsis” (45, 29). Free from the demands of closure and from the narrative dictates to which the rest of the film is beholden (from which epistemic ambivalence emerges), the scene serves as a utopian—that is to say, impossible—space in which “there was no murder,” and we, like Laura, are “safe, protected by Special Agent Dale Cooper” (29). Laura is safe from physical and epistemic violence; viewers are safe from the need to contend with epistemic ambivalence and reflect upon complicity with violence; and Cooper is there, dependable as ever. It would be reasonable to suspect, based on everything that has been depicted leading up to this and on the scene’s suspension from both the show and the rest of the film, that the “hope” (29) it offers is compromised, even fallacious, and that to believe in it is also in a sense to symbolically close one’s eyes to what has been shown; and yet hope, however ironized, is what the scene seems to be offering—hope perhaps that it can resolve the pressures of its own ambivalence?

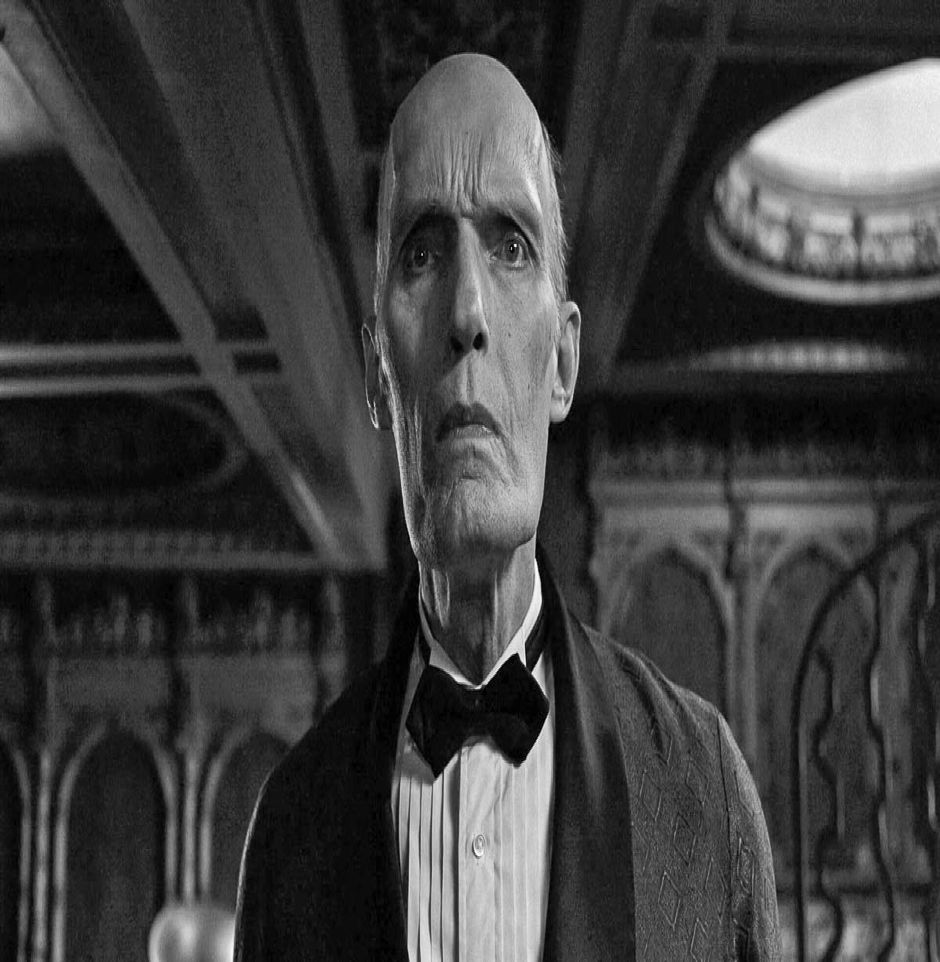

Twin Peaks: The Return destroys that hope. Rather than leaving Laura in the ambiguous safety Mactaggart describes, suspended from the demands of relative narrative cohesion, The Return reintroduces her as a potentially knowable object, intimating that Cooper, finally, might be able to unambivalently save her—and, concomitantly, that viewers might finally achieve real closure. By The Return’s finale, all comfort has been revoked, and viewers are left—like Cooper, who is now presented as a disconcerting amalgam of regular Cooper and his doppelganger Mr. C—stranded in an unknown time and space. As the mysterious Fireman (Carel Struycken) tells him in the reboot’s opening scene, “you are far away.”

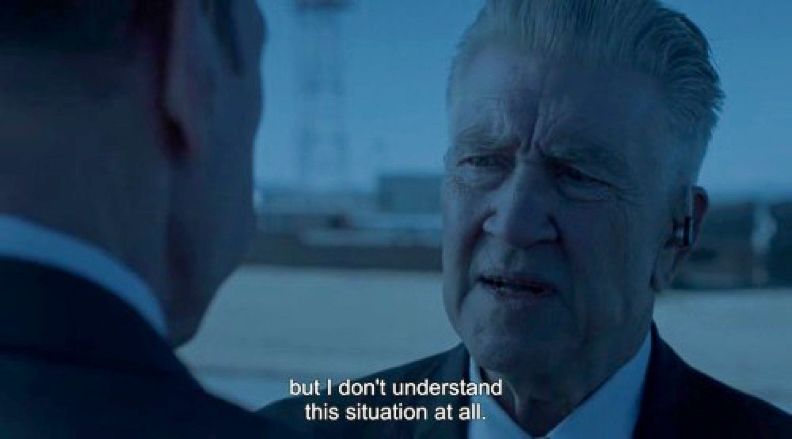

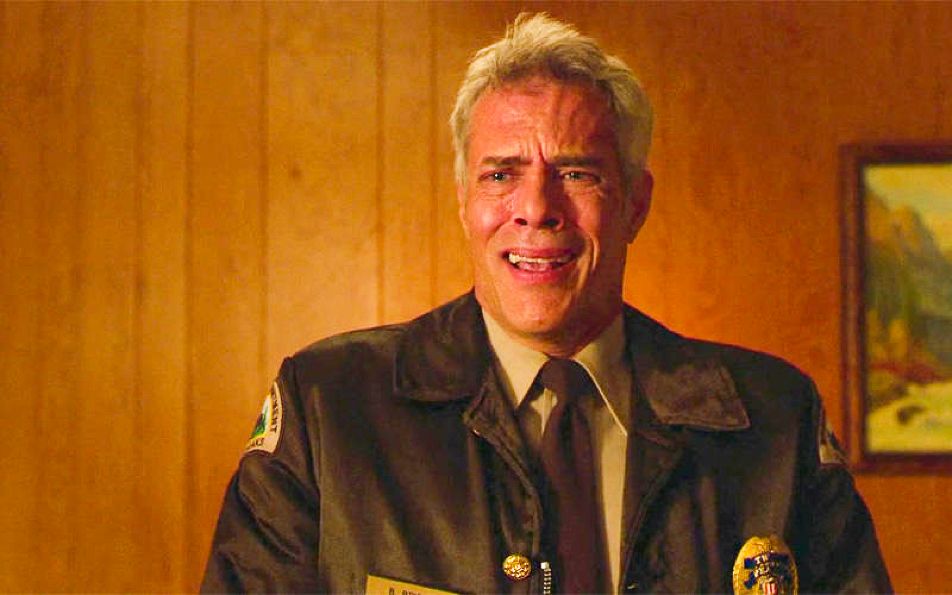

The Return ruthlessly expands FWWM’s discarding of much of what characterized the original series. The bulk of the episodes take place outside of Twin Peaks, and the town itself is ghostly, populated by sluggish versions of characters we once knew, who themselves are outnumbered by a witless younger generation of new, generally amoral characters whose dysfunctional lives play out as, for the most part, non-sequiturs or evocations of a generalized sense of decay. Viewers are presented with “a phantasmagoria of long, dazed shots; extended silences devoid of music; and bizarre dialogue almost uniformly spoken with the slow, weighty cadence of someone trying to hint at something else” (Hudson). The “something else” being hinted at, I suggest, is the original series and its comparatively whimsical search for meaning and answers, the loss of which is now almost total. This is indicated by one of the few scenes in which elements of the original break through, such as when Bobby Briggs (Dana Ashbrook), now a Deputy in the Twin Peaks Police Department, encounters a photograph of Laura Palmer. The image of Laura causes him to burst melodramatically into tears to the familiar—but in this context jarring—rise and fall of “Laura’s Theme.”

Occurring only once more in the entirety of The Return—when Cooper, in the words of Mike, “finally” (S03E15) awakens from the straitjacket of Dougie Jones—the incongruity of the song’s recurrence suffuses the scene with an air of artifice, suggesting that it has less to do with evoking the pleasures of the original show than it does with highlighting their absence. They, like Laura Palmer and the ongoing mystery the original could have provided had the epistemic violence of closure not been imposed upon it, are gone, and this shadow is what remains.

Dougie serves a similar purpose. While not without charm or humor, the slow odyssey of Cooper’s emergence from Dougie, alongside the story of Mr. C and his search for mysterious coordinates, serves as the primary source of mystery from Parts 3 and 4 onwards until the destruction of BOB at the hands—or rather, green-gloved hand—of cartoonish deus ex machina Freddie (Jake Wardle). Dougie’s blank intoning of linguistic tropes from the original show, always slightly off-key, gestures tantalizingly toward something that is and will remain absent. The Return thus seems to be incorporating viewer nostalgia only to skewer it—the melancholia of which Dougie’s oddly inscrutable face frequently reflects.

This section of the narrative, spanning roughly Parts 3 to 15, imposes a more brutal and unforgiving atmosphere of epistemic ambivalence than the original and FWWM, subjecting viewers to hours of what in retrospect can feel like arbitrary—or at least mechanical—irresolution. While inviting viewers to connect the dots and find meaning in what they are witnessing, and hinting toward the payoff of a dramatic confrontation between Cooper and Mr. C in which all of the details fans have been meticulously charting will add up to something more conclusive than the sum of their parts, this section of The Return instead constructs a mystery the resolution of which, we eventually learn, is largely incidental. In doing so, it performs the hollowness of inhabiting the irresolution and inaction of an epistemic ambivalence confronted “with imperfect courage” (S02E11), trapped in the loop of seeking a closure that will never come—a kind of sickness that is evoked by the town of Twin Peaks’ pointedly unexplained but ever-encroaching backdrop of decay.

Nested within this section, however, is Part 8’s striking narrative revelation—a revelation that, at least superficially, seems to provide answers to mysteries viewers have been puzzling over for decades.

The Trinity Test, representing the most catastrophic and misguided example of the evil that men do, activates the Convenience Store, and the Woodsmen operating it conduct some kind of glitchy, electrically charged activity resulting in the emergence of the Experiment (Erica Eynon) from within the explosion’s maelstrom. The Experiment then ejects BOB from its mouth in the form of an orb, alongside an egg containing a mutant creature that will eventually crawl into the throat of a young Sarah Palmer. After passing through a viscous gold blob inside the explosion, we travel interdimensionally to an enormous fortress-like structure rising from an abyssal purple ocean. Inside the Fortress, the Fireman witnesses BOB’s emergence. He floats into the air and releases from his mouth a starlike golden arborescence that forms into an orb containing Laura’s face, which is then launched via a brassy gold contraption toward a screen image of Earth. Laura, it may be concluded, is a force of good sent by an oblique yet seemingly benevolent godlike entity to combat the evil humanity has unleashed upon itself; the Experiment is a manifestation of Judy—that “extreme negative force” (S03E17)—summoned by the intensity of nuclear experimentation.

Such relative forthrightness, however, is uncharacteristic of the Peaksverse, and as such warrants closer attention. Laura, according to depiction of her thus far, is not an emblem or force of unambivalent good, but rather is multifaceted and compromised—characterized, as Lynch himself describes, by “contradictions: radiant on the surface but dying on the inside” (Rodley 184). Once a plot device murdered by closure, then a character in her own right capable of exerting agency (albeit within the constraints of the past’s dictates), her literal objectification into a glowing orb with a symbolic moral function seems incongruous. As such, I suggest Orb-Laura functions as an ironic response to the desire for an ending in which knowledge brings closure that Peaks as a whole both compels and refutes, as well as a self-consciously complicit reobjectification of Laura Palmer.

As the essence of goodness, opposed to the evil that is BOB, Laura once again becomes a vehicle for knowledge that purports to finally provide some answers and reassurance. And yet, in this purified, abstracted form, bereft of contradictions, she is irreconcilable with the ambivalent moral and epistemic logic of the Peaksverse—which is suggested by the image of her floating slowly toward Earth, never reaching, at least in pristine Orb-form, the already compromised human world of the diegesis. The structurally anomalous function of Part 8 in relation to the rest of The Return—it is never referred directly back to elsewhere in the narrative—echoes the narrative suspension of FWWM’s final scene. But where that scene offered catharsis as opposed to closure, Part 8 purports to provide closure while in fact irreversibly revoking Laura’s ambiguous safety and castigating both viewer desire for and its own ambivalent attachment to the possibility of closure. This interpretation is bolstered by analysis of the Fireman’s gaze.

In the Fortress, the Fireman watches the explosion on a giant screen in a theatre-like room. A shot-reverse-shot sequence lingers on his troubled face staring at both the screen and—as is emphasized by the shot’s discomfiting length—at the viewer. Where FWWM incorporated the viewer’s desire for answers via an ironized male gaze that highlights its and viewers’ complicity in violence, The Return turns its gaze, via the Fireman, directly upon both us and itself.

Given that the Fireman is watching what viewers have just watched while also watching them do so, it could be suggested that he is indicting both viewers and the show for the “evil” that has been “do[ne],” and implying that only Laura, as the essence of goodness, can heal things—that she is the only source of hope remaining for a world that is, as the title of Au Revoir Simone’s second Roadhouse song suggests, “violent” and “flammable” (S03E09). Instead, I suggest, the scene performs—much as the ironic male gaze does in FWWM—The Return’s own complicity in the violence its narrative depicts: despite the ongoing critique of viewer desire for closure, the show itself is just as complicit as we are and just as trapped in epistemic ambivalence. Viewed in this light, the Fireman’s gaze is not indicting viewers; it is siding with them, by giving them something impossible within the show’s own epistemic logic as a salve against the uncertainty and complicity that characterizes its diegetic world. The Laura given by the Fireman is the Laura many viewers may have wanted: comprehensible and resolute in meaning. The scene provides, however briefly, the impossible pleasure of unambivalence before returning to the brutal ambiguity of the show’s world in which there are no definite answers, and, as the finale will suggest, no end to Laura’s suffering. It is as if the show is responding auto-exegetically to its own critique of (its own) complicity in FWWM by staging (in a theatre, no less) a performance of its own complicity, granting itself and viewers the pleasure of satisfied knowledge at the same time as admitting implicitly that this knowledge is at best dissatisfying and at worst the objectification of Laura taken to a beguilingly logical extreme.

I have suggested that The Return critically responds to and consolidates as integral to the Peaksverse discourses of epistemic ambivalence and complicity with gendered violence that were established in the original series—and, more explicitly, in FWWM—by following the past’s dictates. The original series, I have suggested, compelled viewer identification with Cooper and his eccentric quest for answers that were never supposed to be revealed. In FWWM, Cooper is mostly absent and ineffectual, and while many viewers continued to crave narrative closure, the film served largely to critique the gendered violence inherent in what it framed as an objectifying desire for unambivalent knowledge. Nevertheless, as Mactaggart’s analysis of the final scene implies, Cooper remained a source of hope. Much of The Return’s duration is spent teasing viewers with the possibility that a familiar Cooper will return and, finally, provide the closure they may have wanted. The show’s finale dispels that hope irrevocably by effecting upon viewers a disidentification from Cooper—a process that involves not rejecting the object from which one is disidentifying but renegotiating one’s attachment to the “harmful” elements with which it is encoded in order to “invest it with new life” (Muñoz 12).

While the final two episodes appear to show Cooper trying and failing to save Laura by altering the timeline, preventing her murder and taking her “home” (S03E17) to the Fortress, it seems more likely that Cooper is instead weaponizing Laura in order to carry out the plan that, as is obliquely revealed in Part 17, he, Cole, and Major Garland Briggs (Don S. Davis) concocted to “lead [them] to Judy.” In this reading, the home Cooper returns Laura to is her mother’s house, inhabited—via Sarah Palmer—by Judy, so that Laura (as emissary of goodness) can fulfil the purpose for which she was made: to destroy Judy. Cooper thus prevents her murder at the last minute—in the process revoking the ambiguous sanctuary described by Mactaggart—to deprive Judy of the garmonbozia produced from Laura by BOB/Leland, so that Judy will expose herself and attempt to recover it. Instead, it appears, Judy tricks Cooper, ripping Laura into an alternate reality in which the plan fails, leaving Cooper trapped as another source of sustaining “garmonbozia” via his suffering.

As I have argued, Orb-Laura, and thus her function as weaponizable essential goodness, is incongruous with the show’s broader epistemic logic. As such, my suggestion is that the final two episodes serve to consolidate epistemic ambivalence as being integral to understanding the show while also demonstrating to viewers a more ethical and less circular way of responding to our and its complicity in physical, symbolic, and epistemic violence. The Cooper who emerges in these episodes is—as are viewers—fundamentally compromised by participation in the reobjectification of Laura as a symbol of goodness and thus as a vehicle for knowledge and a bearer of meaning geared toward closure. As the Fireman puts it in Part 1, “It’s in our house now.”

Like Laura (now in the guise of Carrie Page), in the finale viewers have no definite idea what is happening, nor any real agency over it. Much as what is happening to her appears to be doing so beyond her control, so viewers are dragged along pervasive dark highways toward an uncertain conclusion, passenger to an eerily unrecognizable Cooper.

The disidentification from Cooper that the show has been building toward is consolidated by the final scenes, which depict the failure of his knowledge to achieve—and thus the show’s capacity to provide viewers with—anything like closure. Confronted with this failure, he lurches slowly, confounded, uncertain even of what the year is: a question the answer to which The Return does not provide. Instead, the final scene encourages viewers to renounce the quest for closure, to interrogate their complicity with and renegotiate the terms of their investment in its violence, by shifting focus—and thus, potentially, identification—to Laura, without needing to know exactly what is happening or what it means (much as Laura herself seems not to). In the penultimate shot prior to the credits, Sarah Palmer’s disembodied voice calls Laura’s name out from the house. Shifting to a close-up on her face, Laura screams her familiar horrific scream, offering no resolution but instead returning viewers to and leaving them with what was there all along: Laura Palmer and the trauma that has been inflicted upon her. In giving Laura the final word, the show suggests that rather than continuing to search for closure viewers might negotiate a more ethical viewing position by re-engaging with Laura’s trauma and by ceasing to use her as a bearer of meanings that ultimately propagate forms of gendered epistemic violence in which we and Twin Peaks itself nevertheless remain complicit.

Works Cited

Blake, Linnie. “Trapped in the Hysterical Sublime: Twin Peaks, Postmodernism, and the Neoliberal Now,” Return to Twin Peaks: New Approaches to Materiality, Theory, and Genre on Television, edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock and Catherine Spooner, Palgrave MacMillan, 2015, pp. 229-245.

Clute, Shannon Scott, and Richard L. Edwards. The Maltese Touch of Evil: Film Noir and Potential Criticism, Dartmouth College P, 2011.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding/Decoding,” Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-1979, edited by Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hobson, Andrew Lowe, and Paul Willis, Routledge, 2003, pp. 128-138.

Hallam, Lindsay. “Women’s Films: Melodrama and Women’s Trauma in the Films of David Lynch,” The Women of David Lynch, edited by David Bushman, Fayetteville Mafia P, 2019, pp. 15-30.

Hibberd, James. “Twin Peaks: David Lynch holds a weird press conference,” Entertainment Weekly, 10 Mar. 2017, https://ew.com/tv/2017/01/09/twin-peaks-david-lynch-press-conference.

Hudson, Laura. “Twin Peaks Recap: I Don’t Understand This Situation At All,” Vulture, 27 Apr. 2017, https://www.vulture.com/2017/05/twin-peaks-recap-part-three-part-four.html.

Lynch, Jennifer. The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, Gallery Books, 1990.

Mactaggart, Allister. The Film Paintings of David Lynch: Challenging Film Theory, Intellect, 2010.

McGowan, Todd. The Impossible David Lynch, Columbia UP, 2007.

Morley, David. “Unanswered Questions in Audience Research,” The Communication Review, 9:2, 2006, pp. 101-121.

Mulholland Drive. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Naomi Watts and Laura Elena Harring, Universal Pictures, 2001.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Visual and Other Pleasures, Indiana UP, 1989, pp. 14-28.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queer of Color and the Performance of Politics, U of Minnesota P, 1999.

Rodley, Chris, and David Lynch. Lynch on Lynch, Faber and Faber, 2005.

Stern, Marlow. “David Lynch on Transcendental Meditation,True Detective, and Collaborating with Kanye West,” The Daily Beast, 6 Oct. 2014, https://www.thedailybeast.com/david-lynch-on-transcendental-meditation-true-detective-and-collaborating-with-kanye-west.

Twin Peaks. Directed by David Lynch et al., performances by Kyle MacLachlan, Sheryl Lee, Ray Wise, and Miguel Ferrer, ABC, 1990-1991.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Sheryl Lee, Ray Wise, Kyle MacLachlan, Miguel Ferrer, and David Lynch, CIBY Pictures, 1992.

Twin Peaks: The Return. Directed by David Lynch, performances by Sheryl Lee, Kyle MacLachlan, Miguel Ferrer, and David Lynch, Showtime, 2017.

Weinstein, Steve. “Is TV Ready for David Lynch?” Los Angeles Times, 18 Feb. 1990, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-02-18-ca-1500-story.html.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway, U of Washington P, 2000.